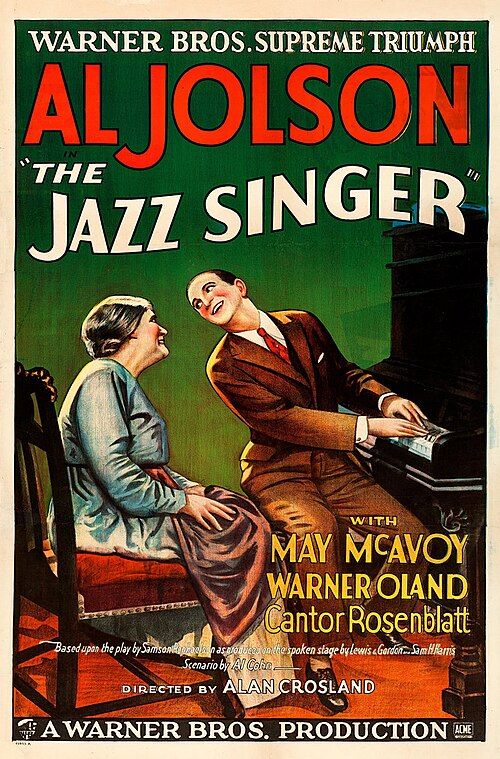

The Jazz Singer

"You ain't heard nothin' yet!"

Plot

Jakie Rabinowitz, the son of a devout Jewish cantor, defies his father's traditional expectations by pursuing his passion for jazz music, running away from home at a young age. Years later, he has transformed into Jack Robin, a successful jazz performer on the verge of his big Broadway break, but his past comes calling when he returns to his old neighborhood. Jack faces an impossible dilemma when his dying father asks him to sing Kol Nidre at the synagogue on Yom Kippur, forcing him to choose between his career-defining performance and his sacred family duty. In a groundbreaking resolution that bridges old and new, Jack manages to honor both his heritage and his modern aspirations, symbolizing the cultural tensions of immigrant families in America. The film culminates with Jack finding acceptance from both his community and the entertainment world, suggesting that tradition and progress can coexist.

About the Production

The film was shot as a silent movie with synchronized musical score and sound effects using the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system. The decision to add dialogue sequences came during production when Al Jolson improvised his famous line 'You ain't heard nothin' yet!' during a musical number. The film used two different cameras - one for the picture and one synchronized to record the sound - requiring precise technical coordination. The sound sequences were filmed separately from the silent portions, creating a hybrid format that was revolutionary for its time.

Historical Background

The Jazz Singer emerged during a period of massive technological and cultural transformation in America. The 1920s saw the rise of jazz music, the Harlem Renaissance, and significant changes in social attitudes toward immigration and assimilation. The film reflected the tensions between traditional immigrant values and the allure of American modernity, particularly relevant for Jewish families like the Rabinowitzes. Technologically, the film industry was at a crossroads, with several competing sound systems vying for dominance. Warner Bros.' investment in Vitaphone was a gamble that paid off spectacularly, coinciding with the public's growing appetite for talking pictures. The film's release came just before the Great Depression, and its success helped establish the Hollywood studio system that would dominate American entertainment for decades.

Why This Film Matters

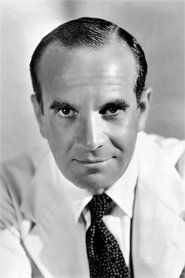

'The Jazz Singer' represents one of the most pivotal moments in cinema history, marking the transition from silent to sound films and revolutionizing the entertainment industry. Its success effectively ended the silent film era within two years of its release, forcing studios to convert to sound technology and ending the careers of many silent stars whose voices didn't translate well to talkies. The film also broke new ground in its portrayal of Jewish-American identity on screen, presenting themes of assimilation, generational conflict, and cultural negotiation that resonated with immigrant audiences. Al Jolson's performance, including his use of blackface in some numbers (controversial today but common then), reflected the complex racial and cultural dynamics of 1920s America. The film's commercial success demonstrated that audiences were hungry for sound, leading to rapid technological innovation and the establishment of new genres, particularly the movie musical.

Making Of

The production of 'The Jazz Singer' was fraught with technical challenges as Warner Bros. was pioneering the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system. The studio had invested heavily in this technology and needed a hit to avoid bankruptcy. Director Alan Crosland had to coordinate two separate recording processes simultaneously - the visual photography and the audio recording - which required unprecedented precision. The sound sequences were filmed at a slower speed (24 frames per second) compared to silent films (16-18 fps) to improve audio quality. Al Jolson, already a massive star in vaudeville and Broadway, brought his own theatrical style to the film, often improvising and adding his own flourishes to the musical numbers. The decision to include dialogue came after production had begun, making the film a hybrid of silent and sound techniques. The famous scene where Jolson sings to his mother was shot in one take with live orchestra accompaniment, a technical marvel for the time.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Hal Mohr represents a transitional style between silent and sound filming techniques. The silent sequences use the dramatic lighting and expressive camera work typical of late silent cinema, while the sound scenes required more static camera placement due to the limitations of early sound recording equipment. Mohr had to contend with noisy cameras and the need to keep microphones hidden, leading to more conservative framing in dialogue scenes. The film uses soft focus and backlighting particularly effectively in the musical numbers, creating a dreamlike quality that enhances the emotional impact. The contrast between the dark, traditional world of the cantor's home and the bright, modern jazz club is visually emphasized through lighting design and composition.

Innovations

The film's primary technical achievement was the successful integration of synchronized dialogue sequences using the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system. This required solving numerous engineering challenges, including synchronizing separate audio and film recordings, minimizing camera noise, and achieving adequate sound quality. The film demonstrated that talking pictures were commercially viable, leading to rapid industry-wide adoption of sound technology. The production also pioneered techniques for recording musical performances and dialogue simultaneously, laying groundwork for future sound films. The hybrid format - combining silent sequences with synchronized sound - proved to be a transitional solution that helped audiences and the industry adapt to the new technology.

Music

The soundtrack features a mix of traditional Jewish liturgical music, popular jazz standards of the 1920s, and original songs composed by Louis Silvers, who won an Academy Award for his work. Key musical numbers include 'Blue Skies,' 'My Mother's Eyes,' 'Toot, Toot, Tootsie,' and the climactic 'Kol Nidre.' The Vitaphone recording process captured the music on 16-inch discs synchronized with the film projector, creating a rich audio experience for the time. The soundtrack's blend of sacred and secular music mirrors the film's central theme of cultural negotiation. Jolson's powerful voice and emotional delivery style, honed in vaudeville, brought unprecedented energy to the screen performances.

Famous Quotes

"Wait a minute, wait a minute, you ain't heard nothin' yet!"

"I'm gonna sing this jazz for my mother!"

"You'd better keep a civil tongue in your head!"

"I'm a jazz singer at heart!"

"Mother, I'm going to be a great singer someday!"

"This is not for me - this is for my people!"

"A jazz singer? What kind of life is that for a Jewish boy?"

"God will forgive you, my son, for following your heart."

Memorable Scenes

- Jakie's father discovering him singing jazz in the saloon and violently disowning him

- Jack's emotional reunion with his mother after years apart

- The 'Blue Skies' performance where Jolson first breaks into spontaneous dialogue

- Jack torn between his Broadway debut and singing Kol Nidre at the synagogue

- The final scene where Jack successfully bridges both worlds, singing jazz with his mother watching proudly

Did You Know?

- This was the first feature-length film with synchronized dialogue sequences, effectively ending the silent film era

- Al Jolson's famous ad-lib 'You ain't heard nothin' yet!' was not in the original script but was so powerful that it was kept in the film

- The film only has about two minutes of actual dialogue; the rest is synchronized music and sound effects

- Warner Bros. risked bankruptcy to finance the Vitaphone sound system and this film

- The film's success saved Warner Bros. from financial ruin and established them as a major studio

- George Jessel, who originated the role on Broadway, turned down the film role when Warner Bros. refused his salary demands

- The film's title was originally going to be 'The Cantor's Son'

- Only about 25% of the film contains synchronized sound; the majority remains silent with musical accompaniment

- The film was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1996

- The jazz club scenes were filmed on a set that was later used for the '42nd Street' musical number in the 1933 film

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics were overwhelmingly positive, with Variety declaring it 'undoubtedly the best thing Vitaphone has ever put on the screen' and praising Jolson's performance as 'electrifying.' The New York Times called it 'a momentous event' in cinema history, though some critics were initially skeptical about the future of talking pictures. Modern critics recognize the film's historical importance while acknowledging its technical limitations and dated elements. Roger Ebert included it in his Great Movies collection, noting that while 'only a small part of the film has dialogue, its impact was revolutionary.' The film maintains a 92% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with critics consensus highlighting its historical significance despite its primitive sound technology by modern standards.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences were electrified by the film's novelty, with theaters experiencing unprecedented demand for tickets. Reports from the premiere described crowds lining up around the block and standing ovations during Jolson's musical numbers. The film's success was not just about the technical innovation but also Jolson's charismatic performance, which translated his vaudeville stardom to the screen. Contemporary audiences particularly responded to the emotional family drama and the film's message about balancing tradition with modernity. The film ran for months in major cities and was re-released multiple times, with audiences returning to experience the new technology. Even viewers who had seen the stage version were captivated by the addition of sound, which made the story more immediate and emotionally resonant.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Award for Best Writing, Adaptation (1927/28) - Alfred A. Cohn

- Academy Award for Engineering Effects (Special Award) (1927/28) - Warner Bros.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Jazz Singer (1925 Broadway play)

- Vaudeville performance traditions

- Jewish liturgical music

- 1920s jazz culture

- Immigrant literature of the early 20th century

This Film Influenced

- The Singing Fool (1928)

- Say It With Songs (1929)

- The Merry Widow (1934)

- 42nd Street (1933)

- The Great Ziegfeld (1936)

- Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942)

- The Jolson Story (1946)

- A Star Is Born (1937)

- Singin' in the Rain (1952)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Library of Congress and selected for the National Film Registry in 1996. Multiple restoration efforts have been undertaken, with the most comprehensive being a 4K restoration by Warner Bros. in 2017 that carefully preserved both the visual elements and the original Vitaphone soundtrack. The original nitrate negatives have been transferred to safety stock, and the film is regularly screened at film archives and classic cinema venues worldwide.