The Last Laugh

Plot

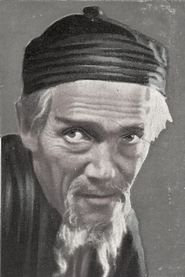

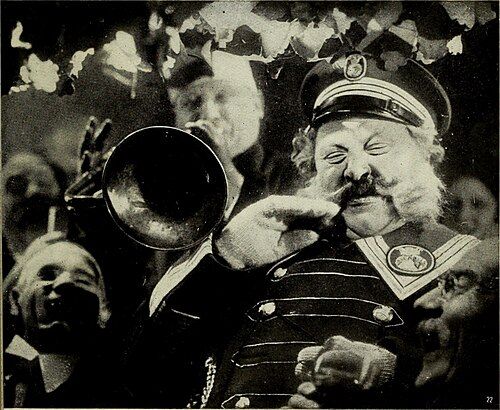

The Last Laugh tells the story of an aging, proud hotel doorman (Emil Jannings) who finds his identity and self-worth entirely wrapped up in his prestigious uniform and position at the Atlantic Hotel. When the hotel manager, believing the old man can no longer handle the physical demands of his job, demotes him to a lowly bathroom attendant, the doorman's world collapses completely. Unable to face his family and neighbors with his new, humiliating position, he steals his old uniform to wear home each evening, desperately maintaining the facade of his former status. The deception is eventually discovered, leading to public humiliation and a complete breakdown of his spirit as he becomes the object of pity and ridicule in his community. In the film's controversial epilogue, the doorman inherits a fortune from a wealthy American who dies in his arms, allowing him to return to the hotel as a rich man, dining lavishly while his former colleagues look on in astonishment.

About the Production

The film was shot entirely in the studio using elaborate sets, including a massive recreation of the hotel's exterior and lobby. The production employed innovative techniques including camera movement on a trolley system and the use of distorted lenses to convey psychological states. Multiple endings were filmed to cater to different international markets, with the original German version being more tragic and the American version featuring the happy inheritance ending.

Historical Background

The Last Laugh was produced during the Weimar Republic, a period of intense cultural and artistic flowering in Germany following World War I and the devastating hyperinflation of 1923. The film emerged from the German Expressionist movement but represented a move toward more realistic settings and psychological depth, marking a transition in German cinema from the stylized, studio-bound fantasies of earlier Expressionist films to what would become known as 'New Objectivity.' The year 1924 was particularly significant as Germany had just stabilized its currency through the introduction of the Rentenmark, leading to economic recovery and increased investment in cultural productions. The film's themes of social status, dignity, and the devastating effects of unemployment resonated deeply with German audiences who had experienced extreme economic instability and social upheaval. The hotel setting itself reflected the cosmopolitan, modernizing Berlin of the 1920s, while the doorman's plight spoke to broader anxieties about technological progress making human labor obsolete in an increasingly mechanized society.

Why This Film Matters

The Last Laugh represents a watershed moment in cinema history, fundamentally changing how stories could be told visually without relying on text. Its technical innovations, particularly the fluid camera movements and subjective cinematography, influenced filmmakers worldwide and helped establish cinema as a distinct artistic medium separate from theater. The film's commercial success internationally demonstrated that German cinema could compete with Hollywood on artistic and technical grounds, contributing to what became known as the 'Golden Age' of German film. Its psychological approach to character study and its exploration of class consciousness and social humiliation influenced later realist movements in cinema. The film's impact can be seen in the works of directors ranging from Orson Welles to Stanley Kubrick, who adopted similar techniques of camera movement and visual storytelling. In Germany, it cemented Emil Jannings' status as one of the greatest actors of his era and established F.W. Murnau as a master director, leading to his eventual move to Hollywood. The film's examination of how identity is tied to social position continues to resonate in contemporary discussions about labor, dignity, and social status.

Making Of

The production of The Last Laugh marked a significant collaboration between director F.W. Murnau and cinematographer Karl Freund, who together developed revolutionary camera techniques that would influence cinema for decades. Freund designed and operated what became known as the 'unchained camera,' mounting it on a trolley system that could glide smoothly through the hotel set, creating unprecedented fluidity of movement. The famous opening shot, which appears to descend from the heavens into the hotel lobby, was achieved by mounting the camera on an elevator and using a specially constructed set. Emil Jannings, already a major star in German cinema, underwent extensive preparation for his role, studying real hotel doormen and practicing their distinctive movements and posture. The production team built an enormous, multi-level hotel set that allowed for dramatic camera movements and angles, including shots that would sweep up and down the grand staircase. Murnau was notoriously demanding on set, often requiring dozens of takes to achieve the precise emotional tone and visual composition he wanted. The film's lack of intertitles presented a unique challenge, requiring Murnau and his team to devise purely visual methods of conveying exposition and emotional states.

Visual Style

Karl Freund's cinematography in The Last Laugh revolutionized film language through its unprecedented camera mobility and subjective visual perspective. The film features what was then called the 'unchained camera' technique, with the camera gliding through space in ways that had never been seen before, including the famous opening shot that appears to descend from above into the hotel lobby. Freund employed innovative techniques such as mounting the camera on bicycles, elevators, and even strapping it to his chest to achieve fluid movement through the elaborate hotel set. The cinematography uses visual distortion to convey psychological states, with the world appearing to warp and spin during the doorman's drunken scenes through the use of special lenses and camera movements. Lighting techniques borrowed from German Expressionism create dramatic contrasts between the opulent hotel and the doorman's humble living quarters. The camera often assumes the doorman's point of view, particularly in scenes where he feels humiliated, with low angles making others appear to look down on him. The film's visual storytelling is so complete that it eliminates the need for intertitles entirely, with the cinematography conveying narrative information, emotional states, and character relationships purely through visual means.

Innovations

The Last Laugh pioneered numerous technical innovations that would become standard in cinema, most notably the 'unchained camera' technique developed by cinematographer Karl Freund. The film employed what was essentially the first camera dolly system, allowing for smooth, fluid movement through space rather than the static shots typical of the era. The production team developed special camera mounts and rigging to achieve shots that would be commonplace decades later, including crane shots and tracking shots that follow characters through the elaborate hotel set. The film's use of subjective camera techniques, where the camera represents the character's point of view, was revolutionary and influenced the development of psychological cinema. Special lenses and filters were used to create visual distortions that convey the protagonist's emotional state, particularly in the famous drunken sequence. The production's complete elimination of intertitles was a bold technical and artistic choice that forced the development of purely visual storytelling methods. The film's lighting techniques, combining naturalistic and expressionistic approaches, created a distinctive visual style that influenced cinematography for decades. The elaborate hotel set was designed specifically to accommodate the innovative camera movements, with removable walls and specially constructed pathways for the camera equipment.

Music

As a silent film, The Last Laugh was originally presented with live musical accompaniment that varied by theater and location. The original German score was composed by Giuseppe Becce, who was UFA's house composer and one of the most prolific film composers of the silent era. Becce's score utilized leitmotifs for different characters and situations, with the doorman's theme changing as his fortunes shifted. In the United States, theaters typically used compiled scores using classical pieces and popular songs of the era. Modern restorations have featured newly composed scores by various artists, including a 2003 version by the Alloy Orchestra and a 2015 score by Timothy Brock that attempts to recreate the style of the original 1924 accompaniment. The music was crucial to conveying emotion and narrative flow, particularly in scenes without intertitles where the score had to provide emotional context. The film's most famous sequence, the doorman's drunken hallucination, was accompanied by dissonant, experimental music that reflected the visual distortion on screen. Contemporary screenings often feature live musical accompaniment, maintaining the tradition of the film's original presentation.

Famous Quotes

Though the film has no dialogue or intertitles, its visual storytelling creates memorable 'quotes' through imagery: The doorman's proud posture in his uniform, his slumped shoulders in the bathroom attendant's coat, the distorted world of his drunken despair, the final triumphant scene of wealth and revenge.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening shot where the camera descends from the heavens into the hotel lobby, establishing the grand setting and the doorman's importance; The scene where the doorman first sees his new uniform and his world collapses; The drunken hallucination sequence with its distorted camera angles and warped perspectives; The humiliating scene where the doorman is caught stealing his old uniform; The final banquet scene where the wealthy doorman enjoys his revenge while his former colleagues watch in astonishment

Did You Know?

- The film is famous for having no intertitles, relying entirely on visual storytelling to convey the narrative

- Emil Jannings wore a prosthetic nose and heavy makeup to age himself for the role, which took hours to apply each day

- The camera was strapped to the cinematographer's chest for certain shots to achieve fluid movement, a technique that was revolutionary at the time

- The hotel set was so elaborate and expensive that UFA kept it standing for several years, using it in other productions

- The film's German title 'Der letzte Mann' literally translates to 'The Last Man,' referring to the doorman's position as the last person guests see when leaving

- Director F.W. Murnau reportedly forced Emil Jannings to actually carry the heavy luggage shown in the film to ensure authentic exhaustion in his performance

- The film's success led to Jannings becoming the first recipient of the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1929

- The distorted camera angles used to show the doorman's drunken state were achieved by using a special anamorphic lens

- The original ending had the doorman dying alone and forgotten in the hotel bathroom, but this was changed after test screenings

- The film was one of the most expensive German productions of its time, with UFA investing heavily in its technical innovations

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics in Germany hailed The Last Laugh as a masterpiece, with particular praise for its technical innovations and Emil Jannings' performance. The film journal Film-Kurier called it 'a triumph of German cinema' and praised Murnau's direction as 'nothing short of genius.' International critics were equally enthusiastic, with The New York Times declaring it 'the most remarkable film of the year' and highlighting its revolutionary camera work. French critics, particularly from the avant-garde, embraced the film as evidence of cinema's artistic potential, with Henri Langlois later calling it 'one of the ten most important films in cinema history.' Modern critics continue to celebrate the film, with Roger Ebert including it in his 'Great Movies' collection and praising its 'breathtaking visual storytelling.' The film maintains a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on critical reviews, and is consistently ranked among the greatest films ever made in polls by Sight & Sound, Cahiers du Cinéma, and other prestigious publications. Critics particularly note how the film's visual techniques perfectly serve its emotional and thematic content, creating what many consider the perfect marriage of form and function in cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The Last Laugh was a tremendous commercial success both in Germany and internationally, with audiences particularly responding to Emil Jannings' powerful performance and the film's emotional story. German audiences, still recovering from economic instability, found the doorman's plight deeply relatable, and the film became a cultural touchstone for discussions about dignity and social status. In the United States, the film broke box office records for a foreign language film, with American audiences marveling at its technical achievements despite the cultural differences. The happy ending added for American audiences proved particularly popular, though some critics felt it compromised the film's artistic integrity. The film's success led to increased demand for German films internationally and helped establish the reputation of German cinema as technically and artistically superior. Contemporary audiences at revival screenings continue to respond strongly to the film, with many noting how its themes remain relevant in today's gig economy and discussions about the dignity of work. The film's emotional power transcends its silent format, with modern viewers often expressing surprise at how completely engaging the story is without dialogue.

Awards & Recognition

- First place in the category 'Most Important German Film' at the 1924 Kinematographen-Kalender

- Recognition at the 1925 International Film Exhibition in Moscow

- Special Commendation from the German Film Critics Association (1925)

- Honored at the 1964 Venice Film Festival as part of a Murnau retrospective

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) - for its expressionist visual style

- Nosferatu (1922) - Murnau's previous work influenced his approach to visual storytelling

- Russian montage theory - particularly Eisenstein's ideas about visual conflict

- 19th century German literature - particularly works by Thomas Mann and Theodor Fontane dealing with social themes

This Film Influenced

- Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927) - Murnau's next film built on techniques developed here

- Citizen Kane (1941) - Welles was influenced by the camera techniques

- The Bicycle Thief (1948) - themes of dignity and social status

- Taxi Driver (1976) - Scorsese cited the subjective camera techniques

- American Beauty (1999) - themes of suburban despair and social pretense

- The Wrestler (2008) - similar themes of aging and professional identity

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Last Laugh is well-preserved with multiple complete prints existing in archives worldwide. The film has been digitally restored several times, most notably by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung in collaboration with the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv. A 4K restoration was completed in 2015, revealing details not seen in previous versions. The original camera negative has been preserved, though some minor deterioration exists in certain scenes. Both the German and American versions survive, allowing for comparison of the different endings. The film is part of the permanent collections of major film archives including the Library of Congress, the British Film Institute, and the Cinémathèque Française.