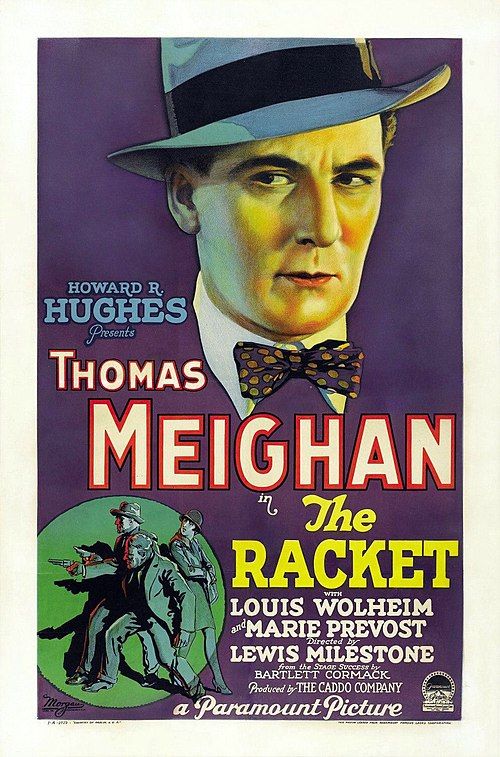

The Racket

"The Story of a City Held in the Grip of Terror!"

Plot

Captain James McQuigg, an incorruptible police captain, arrives in a city dominated by crime boss Nick Scarsi and immediately makes enemies by refusing to accept bribes or bow to corruption. McQuigg's relentless pursuit of Scarsi puts him at odds with both the criminal underworld and his own compromised police department, leading to threats against his life and family. The tension escalates as Scarsi uses his political connections and violent methods to try to eliminate McQuigg, who must rely on his wits and a few loyal officers to fight back. The film culminates in a dramatic confrontation where McQuigg must risk everything to bring Scarsi to justice, exposing the deep-rooted corruption that has infected the entire city. Throughout the battle, McQuigg's determination serves as a moral compass in a world where crime and politics have become indistinguishable.

About the Production

The film was based on a popular 1927 Broadway play by Bartlett Cormack, which itself was inspired by real-life corruption in Chicago. Lewis Milestone, who had just won an Academy Award for 'Two Arabian Knights' (1927), was chosen to direct. The production faced censorship challenges due to its depiction of police corruption and organized crime, requiring careful navigation of the Hays Code precursors. Thomas Meighan, a major star of the era, was specifically cast against type as the heroic police captain, having previously played more romantic leads. The film was rushed into production to capitalize on the public's fascination with gangster stories during the height of Prohibition.

Historical Background

The Racket emerged during a pivotal moment in American history and cinema. Released in 1928, it came at the height of Prohibition (1920-1933), when organized crime syndicates controlled bootlegging operations and wielded enormous political influence in major cities. The film's depiction of corruption between criminals and politicians reflected real concerns about the breakdown of law enforcement and democratic institutions. In cinema, 1928 was a transitional year between silent films and the coming sound revolution - 'The Racket' was among the last major silent releases before 'The Jazz Singer' changed the industry forever. The gangster genre was just beginning to emerge as a distinct category, with this film helping to establish many of its conventions. The film's production coincided with increased calls for film censorship, which would soon lead to the enforcement of the Hays Code in 1930. Its nomination at the first Academy Awards reflected Hollywood's attempt to establish itself as a respectable artistic institution, even as it produced films about the darker aspects of American life.

Why This Film Matters

'The Racket' holds a crucial place in cinema history as one of the foundational texts of the gangster genre. Its depiction of urban corruption and the battle between a lone lawman and organized crime would influence countless films that followed, from 'Little Caesar' (1931) to 'The Godfather' (1972). The film helped establish the archetype of the incorruptible police officer fighting against systemic corruption, a theme that would become a staple of American crime cinema. Its realistic approach to violence and corruption pushed boundaries of what could be shown in mainstream films, contributing to the eventual implementation of stricter censorship codes. The film's success demonstrated audience appetite for gritty, realistic stories about contemporary social problems, encouraging Hollywood to produce more films addressing current events and social issues. 'The Racket' also represents an important transitional moment in Hollywood's self-perception, as the industry began to recognize cinema's potential for serious artistic expression through its recognition at the first Academy Awards. The film's preservation and restoration have allowed modern audiences to appreciate its sophisticated visual storytelling and understand its influence on the evolution of American crime cinema.

Making Of

The production of 'The Racket' was marked by several significant challenges and innovations. Director Lewis Milestone employed innovative camera techniques for the time, including low-angle shots to emphasize the power dynamics between characters. The casting of Louis Wolheim as the villain was particularly inspired - Milestone had worked with him previously and knew his distinctive appearance and gravelly voice would create an unforgettable antagonist. The film's urban setting was created entirely on studio backlots, with impressive miniature work for cityscapes. The production team faced pressure from real-life political figures who were concerned about the film's negative portrayal of city government. During filming, Thomas Meighan insisted on performing many of his own stunts, including a dangerous fall from a height that required careful coordination. The studio invested heavily in the film's marketing, creating an extensive campaign that emphasized its 'ripped from the headlines' authenticity. The transition from stage play to film required significant adaptation, with Milestone adding visual elements and expanding outdoor scenes to take advantage of the cinematic medium.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'The Racket,' executed by veteran cameraman Charles Lang, showcases the visual sophistication of late silent cinema. Lang employed innovative techniques including dramatic low-angle shots to emphasize the power of the gangster characters and high-angle shots to convey the vulnerability of victims. The film features extensive use of chiaroscuro lighting, creating stark contrasts between light and shadow that would later become hallmarks of film noir. Lang's camera work is particularly notable in the action sequences, where he uses dynamic movement and rapid editing to create tension and excitement. The urban sets are photographed with remarkable depth, creating a convincing sense of a sprawling, corrupt city. The film also features impressive tracking shots that follow characters through complex environments, demonstrating the technical prowess of late silent cinema. Lang's use of close-ups is particularly effective in conveying the psychological states of the characters, especially in the confrontations between McQuigg and Scarsi. The visual style balances realism with expressionistic elements, creating a distinctive look that elevates the material beyond typical genre fare.

Innovations

The Racket showcased several technical innovations that advanced the art of filmmaking in the late silent era. The production employed sophisticated miniature photography for establishing shots of the city, creating convincing urban environments that were far more detailed than typical studio backlots. The film's editing, supervised by Lewis Milestone, featured rapid cutting techniques that were ahead of their time, particularly in action sequences where cross-cutting between parallel storylines created maximum tension. The soundstage construction for interior scenes was particularly ambitious, featuring multi-level sets that allowed for complex camera movements and blocking. The film also made innovative use of process photography for certain exterior shots, allowing for the combination of location footage with studio work. The lighting design was unusually sophisticated for its time, using multiple light sources to create depth and dimension in the compositions. The film's special effects, while subtle, included carefully executed matte paintings and glass shots that expanded the visual scope of the production. The preservation and restoration process in 2016 also represented a technical achievement, using digital technology to stabilize the image, repair damage, and enhance contrast while maintaining the film's original visual character.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Racket' was originally presented with musical accompaniment that varied by theater and location. The score was typically provided by the theater's house organist or orchestra, using compiled music from various sources rather than a composed score. The film's mood and pacing were enhanced through carefully selected musical cues, with tense scenes accompanied by dramatic, dissonant music and moments of triumph underscored with heroic themes. The original cue sheets, discovered with the preserved print, suggest a mix of classical pieces, popular songs of the era, and specially arranged stock music. For the 2016 restoration, a new musical score was commissioned to accompany screenings, though it remains faithful to the style and spirit of 1920s silent film accompaniment. The restored version uses a combination of period-appropriate orchestral music and original compositions that enhance the film's dramatic moments without overwhelming the visual storytelling. The music effectively supports the film's themes of corruption and justice, using leitmotifs for different characters and situations. The soundtrack's role in creating atmosphere is particularly important in scenes without intertitles, where music carries the emotional weight of the narrative.

Famous Quotes

You can't fight the whole city, Captain. You'll get yourself killed.

I didn't take this job to make friends. I took it to clean up this town.

In this city, the law and the criminals work together. The only difference is the uniforms.

Justice isn't blind in this town - she's on the payroll.

When you fight a racket, you don't just fight the gangsters. You fight the whole system that protects them.

Memorable Scenes

- The tense confrontation in Scarsi's office where the mob boss tries to bribe Captain McQuigg, showcasing the moral battle between corruption and integrity

- The dramatic rooftop chase sequence where McQuigg pursues one of Scarsi's henchmen across the city skyline, demonstrating innovative camera work and stunt coordination

- The climactic courtroom scene where McQuigg presents his evidence against Scarsi, revealing the extent of the corruption network

- The opening sequence establishing the city's criminal underworld through a series of quick cuts showing various illegal operations

- The emotional scene where McQuigg's family is threatened, raising the personal stakes of his battle against crime

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first films nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture (then called 'Outstanding Picture') at the inaugural 1929 Academy Awards

- The film was considered lost for decades until a complete print was discovered in the Howard Hughes film collection

- Louis Wolheim's performance as the mob boss was so convincing that he received death threats from real gangsters

- The film's release coincided with the height of Prohibition, making its crime themes particularly relevant to contemporary audiences

- Director Lewis Milestone won his first Academy Award the year before for 'Two Arabian Knights', making this a highly anticipated follow-up

- The original Broadway play ran for 119 performances and starred Edward G. Robinson, who would later become famous for gangster roles

- The film was banned in several cities due to its depiction of police corruption and violence

- A remake was planned in the 1950s but never materialized due to difficulties with the Production Code

- The Academy Film Archive preserved the film in 2016 using funding from the National Film Preservation Foundation

- The film's success helped establish the gangster genre as a viable commercial category in Hollywood

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'The Racket' for its bold storytelling and realistic depiction of urban crime. The New York Times hailed it as 'a powerful and timely drama that pulls no punches in its portrayal of city corruption,' while Variety noted its 'gripping narrative and outstanding performances.' Critics particularly singled out Louis Wolheim's performance as the mob boss, with many calling it one of the most convincing villain portrayals of the silent era. The film's direction by Lewis Milestone received widespread acclaim for its innovative camera work and tight pacing. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as an important precursor to the gangster genre, with the British Film Institute describing it as 'a remarkably sophisticated crime drama that anticipates many of the themes and visual styles of later film noir.' The film's nomination for Best Picture at the first Academy Awards was seen as validation of its artistic merits, though some contemporary critics questioned whether such gritty subject matter deserved recognition alongside more prestigious productions. Today, film scholars appreciate 'The Racket' for its historical significance and its role in establishing conventions that would define American crime cinema for decades.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1928 responded enthusiastically to 'The Racket,' drawn by its timely subject matter and reputation for being 'ripped from the headlines.' The film performed strongly at the box office, particularly in urban areas where audiences could relate to its depiction of city corruption and gangster violence. Moviegoers praised the film's excitement and suspense, with many commenting on its realistic portrayal of crime and its fast-paced action sequences. The chemistry between Thomas Meighan and Louis Wolheim was particularly well-received, with audiences enjoying their cat-and-mouse dynamic. The film's success led to increased demand for more gangster pictures, helping establish the genre as a commercial staple. Despite some controversy over its violent content, 'The Racket' avoided the moral panic that would later greet films like 'Little Caesar' and 'The Public Enemy,' perhaps because its hero was clearly established as a moral authority figure. Modern audiences who have seen the restored version often express surprise at its sophistication and visual style, with many noting how well it holds up compared to later sound gangster films. The film's preservation has allowed new generations to appreciate its contribution to American cinema history.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Honorary Award (1929) - Lewis Milestone for 'Unique and Artistic Production' (special award for the year)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Front Page (play)

- Underworld (1927 film)

- Chicago crime stories of the 1920s

- German Expressionist cinema

- Broadway melodramas

- New York journalism

- Realist theater movement

This Film Influenced

- Little Caesar (1931)

- The Public Enemy (1931)

- Scarface (1932)

- G Men (1935)

- The Big Sleep (1946)

- On the Waterfront (1954)

- The Untouchables (1987 TV series)

- The Departed (2006)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was preserved by the Academy Film Archive in 2016 with funding from the National Film Preservation Foundation. For decades, 'The Racket' was considered a lost film, with only fragments known to exist. A complete 35mm print was discovered in the Howard Hughes film collection, which had been acquired by the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. The restoration process involved cleaning the original elements, repairing damage, and creating new preservation masters for both archival and exhibition purposes. The restored version premiered at the Academy's Samuel Goldwyn Theater as part of the 'Lost and Found' film series. The preservation effort ensured that this historically significant film, one of the first Best Picture nominees, remains accessible to scholars and audiences. The Academy Film Archive maintains the original preservation elements and makes the restored version available for screenings at film archives, museums, and special cinema events worldwide.