The Star Boarder

Plot

A young landlady (Minta Durfee) becomes infatuated with her charming star boarder (Charlie Chaplin), leading to various romantic encounters in her boarding house. Her mischievous young son, suspicious of their relationship, decides to investigate and discovers their indiscretions. The boy then creates a magic lantern show featuring shadow puppets that dramatically reenacts the compromising moments he has witnessed. During a public performance for other boarders and neighbors, the child's innocent but revealing expose creates hilarious chaos and embarrassment for the mother and her admirer. The film culminates in a comedic resolution as the embarrassed parties must deal with the consequences of their exposed relationship.

About the Production

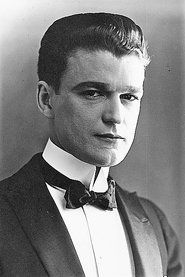

This was one of Chaplin's early films at Keystone Studios, produced during his first year in American cinema. The film was shot quickly in the typical Keystone fashion of one or two days, utilizing the studio's indoor sets and minimal outdoor locations. The magic lantern sequence was particularly innovative for its time, requiring careful choreography and lighting to create the shadow puppet effects. George Nichols, an experienced actor-turned-director, was one of several directors Chaplin worked with at Keystone before taking full directorial control of his films.

Historical Background

1914 was a watershed year in cinema history, marking the transition from short films to feature-length productions and the establishment of Hollywood as the center of American filmmaking. World War I had just begun in Europe, affecting international film production and distribution, but American cinema was experiencing unprecedented growth. The Keystone Studios under Mack Sennett was pioneering the art of film comedy, developing the slapstick style that would dominate early cinema. Charlie Chaplin, who had joined Keystone in late 1913, was rapidly becoming one of the most popular comedians in the world. The film industry was still in its infancy, with most productions being one-reelers (10-12 minutes) shot in a matter of days. This period saw the development of many film techniques and narrative conventions that would become standard in cinema. The magic lantern show in 'The Star Boarder' reflects the transitional nature of 1914 cinema, bridging Victorian entertainment forms with emerging film technology.

Why This Film Matters

'The Star Boarder' represents an important milestone in Charlie Chaplin's artistic development and the evolution of American film comedy. While not as well-known as Chaplin's later masterpieces, it showcases his early experimentation with character development and narrative structure. The film's use of a child's perspective to expose adult hypocrisy was relatively sophisticated for its time and foreshadowed the social commentary that would become central to Chaplin's work. The magic lantern sequence demonstrates early cinema's fascination with visual trickery and special effects, techniques that would become increasingly sophisticated. As a product of Keystone Studios, the film exemplifies the chaotic, energetic comedy style that dominated early American film and influenced generations of comedians. The boarding house setting reflects the urban immigrant experience that was central to American life in the early 20th century. This film, along with Chaplin's other 1914 works, helped establish the template for film comedy that would evolve throughout the silent era and beyond.

Making Of

The production of 'The Star Boarder' took place during Keystone Studios' most prolific period, when they were churning out comedies at a breakneck pace. Chaplin, still relatively new to American cinema, was working under the guidance of Mack Sennett and various directors including George Nichols. The magic lantern sequence required careful planning and coordination, as the shadow puppet effects had to be synchronized with the actors' reactions. Minta Durfee, who was married to Fatty Arbuckle, was a regular Keystone player and had good chemistry with Chaplin. The film was shot in the Keystone Studios facility in Edendale, Los Angeles, which was then a rural area perfect for filming. Chaplin was already beginning to assert creative control over his performances, even though he hadn't yet become the auteur director he would later become. The quick shooting schedule typical of Keystone meant that much of the comedy was improvised on set, with the actors building on established gags and situations.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'The Star Boarder' was typical of Keystone Studios productions in 1914, utilizing stationary cameras with basic panning and tracking movements. The film was shot in black and white on 35mm film, with the standard aspect ratio of the era. The magic lantern sequence required special lighting techniques to create the shadow puppet effects, representing an early form of special effects cinematography. Indoor scenes were lit with the harsh, flat lighting common in early studio productions, while outdoor scenes benefited from natural California sunlight. The camera work was functional rather than artistic, focusing on capturing the action clearly for the audience. The film employed basic close-ups for emotional moments, a technique still relatively new in 1914. The boarding house sets were designed to allow for clear sightlines and comic business, with doorways and staircases serving as comic obstacles. The cinematography served the comedy rather than standing out as artistic, which was typical of Keystone's production philosophy.

Innovations

The most notable technical achievement in 'The Star Boarder' was the magic lantern sequence, which demonstrated early special effects capabilities in cinema. The shadow puppet effects required careful coordination between lighting, props, and performers to create the illusion of a magic lantern projection. This sequence represented an innovative use of in-camera effects and practical effects that predated more sophisticated optical printing techniques. The film also utilized the standard Keystone technical approach of rapid editing and multiple camera setups to capture the chaotic comedy. The boarding house set design allowed for complex staging of comic business, with multiple entrances and exits creating opportunities for farcical situations. While not groundbreaking in terms of cinematography, the film demonstrated the growing sophistication of film language in 1914, with clear narrative progression and character development. The technical aspects served the comedy effectively, showing how Keystone Studios had mastered the craft of producing entertaining comedies quickly and efficiently.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Star Boarder' had no recorded soundtrack but would have been accompanied by live music during theatrical exhibitions. The typical accompaniment would have been provided by a pianist in smaller theaters or a small orchestra in larger venues. The music would have been selected from standard compilations of photoplay music, with pieces chosen to match the mood of each scene - comic music for the slapstick moments, romantic themes for the landlady and boarder scenes, and playful melodies for the child's sequences. The magic lantern show might have featured special musical effects or novelty instruments to enhance the sense of wonder. Some theaters might have used sound effects such as bells, whistles, or other noisemakers to punctuate the comic moments. The musical accompaniment was crucial to silent film experience, helping to guide audience emotions and enhance the comedy. While no specific musical score was composed for this film, the accompanist would have drawn from the extensive library of photoplay music available to theaters of the era.

Famous Quotes

The magic lantern show reveals more than intended - a child's innocence exposes adult indiscretions.

In the boarding house of life, every room holds a secret, and every shadow tells a story.

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic magic lantern show sequence where the child uses shadow puppets to reenact the landlady and boarder's secret encounters, creating hilarious embarrassment as the other boarders watch the unwitting expose unfold.

- The various sneaking scenes where Chaplin and Durfee attempt to have private moments, constantly interrupted by the suspicious child or other boarders.

- The final chaos scene where all characters react to the revelation, with exaggerated expressions and physical comedy typical of Keystone style.

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first films where Chaplin began developing his signature 'Little Tramp' character, though the persona wasn't fully formed yet.

- Minta Durfee was married to fellow comedian Roscoe 'Fatty' Arbuckle at the time this film was made.

- Edgar Kennedy would later become famous for his 'slow burn' comedy style and appear in over 400 films.

- The magic lantern show sequence was considered technically innovative for 1914, showcasing early special effects techniques.

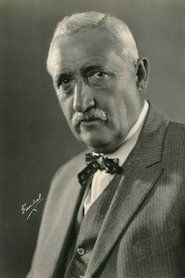

- George Nichols was both a director and actor who appeared in over 200 films, often working with Chaplin during his Keystone period.

- This film was released during Chaplin's explosive rise to fame in 1914, when he made over 30 films in a single year.

- Keystone Studios was known for its chaotic, improvisational style, and this film exemplifies their approach to comedy.

- The film's theme of exposing hypocrisy through a child's innocence was relatively sophisticated for early comedy.

- Chaplin would later take full creative control of his films, but during this period he was still learning the craft of directing.

- The boarding house setting was a common trope in early comedies, allowing for multiple character interactions and misunderstandings.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of 'The Star Boarder' were generally positive, with critics noting Chaplin's growing comic talents and the film's inventive magic lantern sequence. The trade papers of the era, such as Moving Picture World and The New York Dramatic Mirror, praised the film's humor and technical cleverness. Critics particularly appreciated the child's role in exposing the adult characters' indiscretions, seeing it as a fresh approach to comedy. Modern film historians view the work as an important stepping stone in Chaplin's development, noting how it shows his progression from pure slapstick toward more character-driven comedy. The film is often cited in studies of early cinema as an example of how quickly Chaplin was mastering the medium and developing his unique style. While not considered a masterpiece by modern standards, it is valued by Chaplin scholars and silent film enthusiasts for its historical importance and glimpse into the comedian's early career.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1914 responded enthusiastically to 'The Star Boarder,' as they did to most of Chaplin's Keystone productions. The film's mix of slapstick comedy, romantic situations, and the clever magic lantern sequence proved popular with theater-goers of the era. Chaplin's growing star power ensured good attendance for his films, and this one was no exception. The child character's role in the story resonated with family audiences, while the adult situations provided entertainment for older viewers. Contemporary audience reports suggest that the magic lantern show sequence was particularly well-received, with viewers appreciating the technical innovation and comic timing. As with many Keystone films, the fast pace and visual gags played well to the diverse audiences of early nickelodeons and movie theaters. While specific box office figures are not available, the film's success contributed to Chaplin's meteoric rise to become one of the highest-paid and most popular entertainers in the world by the end of 1914.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- French and Italian comedies of the early 1910s

- Vaudeville and stage comedy traditions

- Earlier Keystone comedies featuring similar situations

- Mack Sennett's comedy style

- Max Linder's French comedies

- Music hall and variety show formats

This Film Influenced

- Later Chaplin films featuring children as central characters

- Other Keystone comedies with similar boarding house settings

- Silent comedies that used magic lantern or projection sequences

- Films that employed children exposing adult hypocrisy

- Early sound comedies that adapted similar plot structures

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of 'The Star Boarder' is somewhat uncertain, as is common with many early Keystone films. While not officially listed as lost, complete prints may be rare or fragmented. Some archives and film preservation organizations may hold copies or fragments of the film. The Keystone Studios output from this period suffered from poor storage conditions and the unstable nitrate film stock used in the era. However, given Chaplin's importance in cinema history, efforts have likely been made to preserve his early work. The film may exist in archives such as the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art, or various film preservation foundations. Some versions may be available through restoration projects or in collections of early American cinema. The quality of surviving copies, if any, would vary depending on their preservation history.