The Strong Man

"The Little Man Who Was Afraid of Everything... Except Love!"

Plot

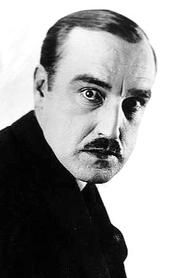

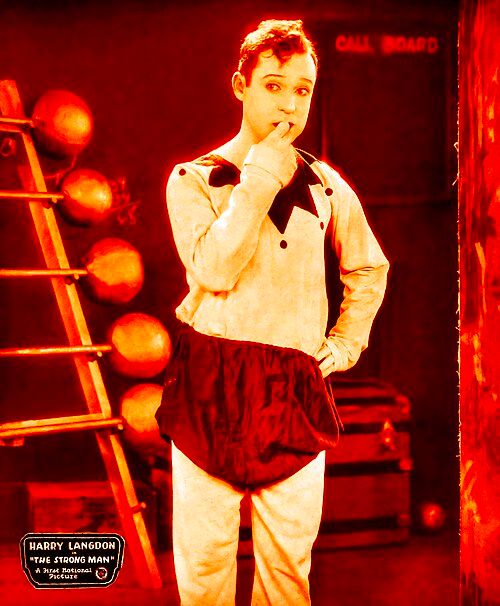

Paul Bergot, a meek and gentle Belgian soldier fighting in World War I, receives heartfelt letters and a photograph from his American pen pal Mary Brown, with whom he falls deeply in love despite never having met her. After the war ends, Paul travels to America as the assistant to Zandow the Great, a vaudeville strongman, all while searching for his beloved Mary Brown. Upon arrival in the rough-and-tumble town of Sandville, Paul discovers that Mary is actually the daughter of the local postmaster and works at the post office. When Zandow becomes incapacitated after a brawl, the timid Paul must unexpectedly take his place on stage as the strongman, leading to chaos and comedy. Through a series of misunderstandings and mishaps, Paul's genuine character and hidden strength ultimately win Mary's heart, proving that true strength comes from within rather than physical power.

About the Production

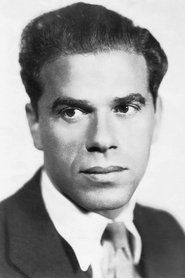

This was the first film that Frank Capra directed for Harry Langdon, marking the beginning of their collaboration. Capra was hired after Langdon's previous director, Harry Edwards, left the production. The film was shot in just over a month during the spring of 1926. The famous post office sequence required extensive set construction and was filmed over several days. Langdon, known for his meticulous preparation, rehearsed his physical comedy routines extensively, sometimes spending hours perfecting a single gag. The strongman competition scene involved actual circus performers and athletes to create authentic atmosphere.

Historical Background

The Strong Man was produced during the golden age of silent cinema in 1926, a period when American film was reaching new heights of artistic and commercial success. The film reflected the post-World War I era's fascination with European immigrants coming to America in search of the American Dream. Released during the Roaring Twenties, it captured the nation's optimistic spirit while also addressing the psychological trauma many veterans carried from the war. The film emerged at a time when comedy was evolving from simple slapstick to more sophisticated character-driven humor. The vaudeville setting was particularly relevant, as vaudeville was still a major form of entertainment in America, though it would soon be eclipsed by talking pictures. The film's release came just before the transition to sound, making it one of the last great silent comedies before the industry was revolutionized by 'The Jazz Singer' in 1927.

Why This Film Matters

'The Strong Man' represents a pivotal moment in American comedy cinema, bridging the gap between pure slapstick and character-driven comedy. Harry Langdon's 'little man' persona influenced countless later comedians, including Jerry Lewis and Woody Allen. The film's exploration of innocence versus corruption in American society reflected broader cultural anxieties during the Jazz Age. Its success helped establish Frank Capra as one of America's most important directors, who would later create films that defined American values during the Great Depression. The movie's theme of finding strength in weakness became a recurring motif in American popular culture. The film also demonstrated how comedy could address serious issues like post-war trauma and immigration while remaining entertaining. Its influence can be seen in later films about unlikely heroes and the fish-out-of-water genre.

Making Of

The making of 'The Strong Man' marked a significant turning point in both Frank Capra's and Harry Langdon's careers. Capra, then a relatively unknown director, was brought in to replace Harry Edwards after creative differences with Langdon. The collaboration initially was tense, as Langdon was accustomed to having significant creative control. However, Capra's vision for combining pathos with comedy resonated with Langdon's style. The famous scene where Langdon must perform as the strongman was filmed in one continuous take, with Langdon performing all his own stunts. The production faced challenges during the post office sequence, where Langdon's meticulous attention to detail caused multiple delays as he insisted on perfecting every comedic moment. The film's success led to a power struggle between Langdon and Capra, with Langdon eventually taking more control over their subsequent collaborations, which some critics believe led to the decline of Langdon's career.

Visual Style

The cinematography by George J. Folsey employed innovative techniques that enhanced the film's comedic and emotional impact. Folsey used soft-focus lighting to emphasize Langdon's innocent, childlike features, creating an almost ethereal quality around the character. The post office sequence utilized deep focus photography to create depth in the chaotic environment, allowing multiple comedic actions to occur simultaneously. Shadow and light were used symbolically throughout the film, with Paul often appearing in soft, warm light during his romantic moments, while the vaudeville world was shot in harsher, more theatrical lighting. The camera movement was deliberately restrained during Langdon's performance scenes to emphasize his physical comedy, but more dynamic during action sequences. The film's visual style influenced Capra's later work, particularly his use of lighting to create emotional atmosphere.

Innovations

'The Strong Man' featured several technical innovations for its time. The film used advanced matte painting techniques for the vaudeville theater scenes, creating the illusion of a much larger space than actually existed. The post office sequence employed a complex system of hidden wires and pulleys to create the illusion of chaos without endangering the actors. The film's editing, particularly in the climactic strongman competition scene, was unusually rapid for the period, using quick cuts to build tension and comedy. The makeup department developed new techniques for creating Langdon's distinctive 'baby face' look, using subtle contouring and lighting rather than heavy prosthetics. The film also experimented with multiple exposure techniques for dream sequences, though these were ultimately cut from the final version. These technical achievements contributed to the film's polished, professional appearance that set it apart from many contemporary comedies.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Strong Man' was originally accompanied by live musical scores in theaters. The typical orchestral score included popular songs of the era such as 'My Blue Heaven' and 'Baby Face' (which became associated with Langdon). The music was carefully synchronized to enhance the emotional beats of the story, with romantic themes for Paul and Mary's scenes and more jaunty, comedic music for the vaudeville sequences. Modern restorations have included newly composed scores by silent film accompanists like Ben Model and the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra. These scores attempt to recreate the musical experience of 1926 while using contemporary recording technology. The film's lack of dialogue actually enhanced its international appeal, as the visual comedy transcended language barriers.

Famous Quotes

Paul Bergot: 'I am not a strong man... but I am a good man.'

Mary Brown: 'Sometimes the strongest hearts come in the smallest packages.'

Zandow: 'The show must go on, even if the strong man can't!'

Postmaster: 'In America, anything is possible if you believe in yourself.'

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic strongman competition where Paul, despite his fear, must perform impossible feats of strength for the audience, leading to both disaster and triumph.

- The chaotic post office sequence where Paul searches for Mary Brown amid a whirlwind of mail, packages, and frantic customers.

- Paul's first arrival in America, where his innocent wonder at the new world contrasts with the rough reality of Sandville.

- The tender moment when Paul finally meets Mary Brown at the post office, their first face-to-face encounter after months of correspondence.

Did You Know?

- This was the film that established Harry Langdon as one of the 'big four' silent comedians alongside Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd.

- Frank Capra considered this film his breakthrough as a director, calling it 'the first picture I ever made that had any quality to it.'

- Harry Langdon was 41 years old when he played the character of Paul, though he appeared much younger on screen.

- The film was so successful that it led to Langdon receiving a contract from Paramount Pictures worth $7,500 per week.

- The character of Zandow the Great was played by Arthur Thalasso, who was actually a professional strongman in real life.

- The film's title sequence featured an innovative animated sequence created by Walt Disney's early studio.

- Priscilla Bonner, who played Mary Brown, was actually married to director Harry Edwards, Langdon's former director.

- The post office set was so elaborate and realistic that it was later used in several other silent films.

- Langdon's distinctive 'baby face' look was created through careful makeup application and lighting techniques.

- The film was one of the first comedies to deal with post-war trauma and the psychological effects of World War I.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'The Strong Man' as a masterpiece of silent comedy. The New York Times called it 'a triumph of cinematic art' and specifically noted Harry Langdon's 'subtle and poignant performance.' Variety magazine declared it 'the best comedy of the year' and predicted great things for both Langdon and Capra. Modern critics have continued to praise the film; Roger Ebert included it in his 'Great Movies' list, calling it 'a perfect blend of comedy and pathos.' The film is often cited by film scholars as a prime example of how silent comedy could achieve emotional depth without dialogue. The British Film Institute ranks it among the top 100 silent films ever made. Critics particularly praise the film's balanced approach to humor and heartbreak, noting how it avoids the sentimentality that plagued many comedies of the era.

What Audiences Thought

The Strong Man was a tremendous box office success upon its release, earning over $1 million domestically, an impressive sum for 1926. Audiences embraced Harry Langdon's gentle, childlike character, finding his innocence refreshing compared to the more cynical personas of other comedians. The film's emotional core resonated with post-war audiences who understood the trauma of returning soldiers. Movie theaters reported packed houses and repeat viewings, with many patrons specifically requesting the film. The film's success made Langdon one of the highest-paid stars in Hollywood, commanding $7,500 per week. Contemporary audience letters preserved in studio archives reveal that viewers particularly connected with the film's message about inner strength and the immigrant experience. The film remained popular through the late 1920s and was frequently re-released in revival theaters during the 1940s and 1950s.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Honorary Award (1929) - Harry Langdon for his unique and brilliant comedy performances

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Charlie Chaplin's 'The Kid' (1921)

- Buster Keaton's 'The General' (1926)

- Harold Lloyd's 'The Freshman' (1925)

- F.W. Murnau's 'The Last Laugh' (1924)

This Film Influenced

- City Lights (1931)

- Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936)

- The Graduate (1967)

- Being There (1979)

- Forrest Gump (1994)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Strong Man has been well-preserved and is considered to be in excellent condition. The film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 2007 for being 'culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.' A complete 35mm print exists in the Library of Congress collection. The film has been digitally restored by several archives including the UCLA Film and Television Archive and the Museum of Modern Art. The restoration process involved cleaning and repairing original nitrate prints, and the results have been released on Blu-ray and DVD by Kino Lorber with newly composed musical scores. Unlike many silent films, 'The Strong Man' was never considered lost, though some early releases were missing minor scenes that have since been recovered from various sources.