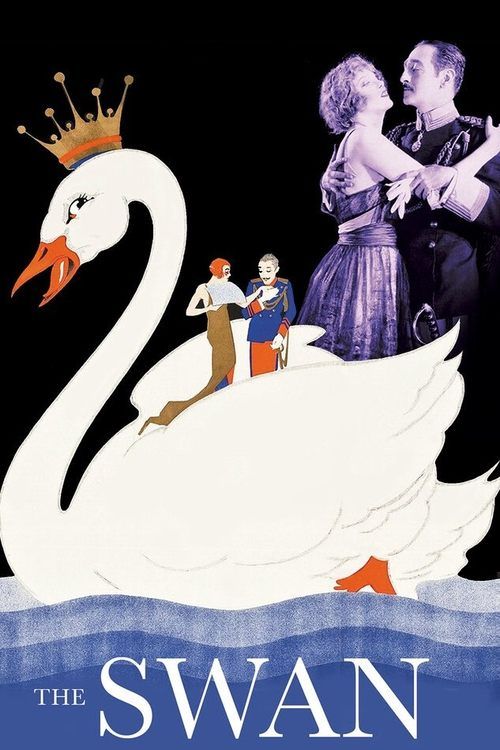

The Swan

"A Royal Romance of Love and Duty"

Plot

Princess Alexandra (Frances Howard), a beautiful but impoverished European princess, is being pressured by her mother to marry for wealth and position rather than love. While visiting her family's estate, she encounters the charming Dr. Walter (Adolphe Menjou), a humble tutor who captures her heart, and the wealthy Prince Albert (Ricardo Cortez), whom her family favors. Torn between duty and desire, Princess Alexandra must navigate the complexities of royal expectations and personal happiness. The film culminates in a series of misunderstandings and revelations that ultimately lead to a resolution where true love triumphs over arranged marriage, though not without significant emotional cost and sacrifice.

About the Production

This was one of Dimitri Buchowetzki's first American films after his immigration from Europe. The production featured elaborate European palace sets designed by Hans Dreier, Paramount's celebrated art director. The film was shot during the height of the silent era's opulence, with extensive costume design by Travis Banton to create authentic royal court atmosphere. Buchowetzki brought his European sensibility to the production, emphasizing visual storytelling over the theatrical origins of the source material.

Historical Background

The Swan was produced during the golden age of silent cinema in 1925, a period when Hollywood studios were reaching their peak of artistic and commercial success. This was an era of significant immigration of European talent to Hollywood, with directors like Buchowetzki bringing continental sophistication to American films. The mid-1920s saw America's fascination with European royalty at its height, despite the country's democratic ideals. The film reflected the post-World War I period's romanticization of old-world aristocracy, contrasting with America's modernity. Paramount Pictures, under the leadership of Adolph Zukor, was establishing itself as one of the major studios, specializing in sophisticated productions that appealed to urban, middle-class audiences. The film's release came just two years before the introduction of sound in motion pictures, making it part of the final wave of purely silent dramatic features.

Why This Film Matters

The Swan represents an important example of Hollywood's adaptation of European theatrical works for American audiences during the silent era. The film helped establish the template for royal romance films that would become a recurring genre throughout cinema history. Its success demonstrated the viability of adapting European plays for silent film audiences, influencing subsequent productions. The film also showcased the growing sophistication of American studio productions, particularly in set design and costume creation. As one of the vehicles for Adolphe Menjou, it contributed to establishing the archetype of the sophisticated leading man that would influence male star personas for decades. The film's themes of duty versus love in royal contexts would be revisited numerous times in cinema, making this early version culturally significant as a prototype.

Making Of

The production faced several challenges typical of mid-1920s Hollywood. Director Dimitri Buchowetzki, still adjusting to American studio methods, often clashed with producers over his European directing style, which emphasized longer takes and more subtle performances than typical American films of the era. Frances Howard, who was contemplating retirement, was particularly difficult during production, demanding multiple retakes and special treatment. The elaborate palace sets required significant construction time and budget, causing delays. The film's score was composed by Josiah Zuro, Paramount's house composer, who created original themes for each character. The production team conducted extensive research into European royal customs to ensure authenticity in costumes and settings, though they took liberties for dramatic effect.

Visual Style

The cinematography was handled by Charles Rosher, one of the era's most respected cameramen who would later win two Academy Awards. Rosher employed soft focus techniques particularly in scenes featuring Frances Howard, creating a romantic, ethereal quality that emphasized her character's princess status. The film utilized extensive lighting techniques to create the illusion of European palace interiors, with Rosher using backlighting and practical lighting effects to simulate candlelight and grand chandeliers. The exterior scenes were shot on Paramount's backlot with painted backdrops combined with real landscaping to create convincing European landscapes. Rosher's camera work showed the influence of German expressionist cinema in its use of shadows and dramatic lighting, particularly in the more emotional scenes.

Innovations

The film featured several technical achievements typical of Paramount's mid-1920s productions. The elaborate palace sets utilized innovative construction techniques to create the illusion of grand European architecture on studio backlots. Special effects included double exposure techniques for dream sequences and sophisticated matte paintings for establishing shots of fictional European kingdoms. The costume department developed new dyeing techniques to create historically accurate royal colors that photographed well in black and white. The film's intertitles were particularly sophisticated, using decorative borders and elegant typography that matched the film's royal theme. Paramount's processing laboratory used new film stock that provided better contrast and detail, particularly important for capturing the intricate details of costumes and sets.

Music

As a silent film, The Swan was accompanied by live musical scores in theaters. Paramount provided a detailed musical cue sheet for theater orchestras, compiled by Josiah Zuro. The score featured adaptations of classical pieces by European composers including Chopin, Tchaikovsky, and Strauss, along with original compositions by Zuro. Major themes were composed for each character: a waltz for Princess Alexandra, a more stately theme for Prince Albert, and a gentle melody for Dr. Walter. The musical accompaniment emphasized the film's romantic and comedic elements, with the orchestra providing emotional cues and dramatic emphasis during key scenes. In larger theaters, the film was often accompanied by full orchestras, while smaller venues used piano or organ accompaniment following the same musical structure.

Famous Quotes

"A princess must learn to love with her head, not her heart." - Princess Alexandra's mother

"In a palace of gold, the simplest truth becomes the most valuable treasure." - Dr. Walter

"Duty is the crown we wear, love is the crown we seek." - Prince Albert

Memorable Scenes

- The grand ballroom scene where Princess Alexandra first encounters both suitors, featuring elaborate choreography and hundreds of extras in period costume

- The garden confrontation between the princess and Dr. Walter, where their true feelings are revealed through subtle gestures and expressions

- The final throne room scene where the princess makes her ultimate decision, utilizing dramatic lighting and camera angles to emphasize the emotional weight of her choice

Did You Know?

- Dimitri Buchowetzki was a Russian émigré who had directed films in Russia, Sweden, and Germany before coming to Hollywood

- Frances Howard retired from acting after this film to marry producer Samuel Goldwyn

- The film was based on Ferenc Molnár's Hungarian play 'A Hattyú Vigjáték Három Felvonásban' (The Swan Comedy in Three Acts)

- This was the first of three adaptations of Molnár's play - followed by 'One Romantic Night' (1930) and 'The Swan' (1956)

- Adolphe Menjou was one of the highest-paid actors of the 1920s, known for his sophisticated matinée idol roles

- Ricardo Cortez, born Jacob Krantz, was one of many actors who changed their names for Hollywood success

- The film's intertitles were written by Julian Johnson, a prominent screenwriter and film critic of the era

- Paramount invested heavily in the production's European settings to capitalize on American audiences' fascination with royalty

- The film's release coincided with the peak of silent film production before the transition to sound

- Despite being a romance, the film contained significant comedic elements that were unusual for royal dramas of the period

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception was generally positive, with Variety praising the film's 'lavish production values' and 'excellent performances.' The New York Times noted Frances Howard's 'charming portrayal' and Adolphe Menjou's 'usual sophistication.' Motion Picture Magazine highlighted the film's 'beautiful photography' and 'authentic European atmosphere.' However, some critics felt the adaptation was too theatrical, with Photoplay noting that 'the stage origins are still visible in the static nature of some scenes.' Modern critics have reassessed the film as a competent but not exceptional example of mid-1920s romantic drama, with particular appreciation for Buchowetzki's visual style and the production design. The film is now studied primarily for its place in the evolution of royal romance films and as an example of European directorial influence on Hollywood.

What Audiences Thought

The film was moderately successful with audiences, particularly appealing to women and fans of romantic melodramas. Contemporary theater reports indicated good attendance in major urban markets, especially in cities with large European immigrant populations who appreciated the authentic court settings. The film's romantic elements and beautiful costumes were particularly praised by female moviegoers of the era. However, it did not achieve the blockbuster status of some other Paramount productions of 1925. Audience letters published in fan magazines of the time expressed appreciation for Menjou's performance and the film's visual beauty, though some found the plot predictable. The film's moderate success was sufficient to justify the later remakes, demonstrating enduring audience interest in the story.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- European royal court dramas

- Ferenc Molnár's theatrical works

- German expressionist cinema

- Hollywood romantic melodramas

- Broadway stage adaptations

This Film Influenced

- One Romantic Night (1930)

- The Swan (1956)

- Roman Holiday (1953)

- The Princess Diaries (2001)

- The Prince and Me (2004)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Swan (1925) is considered a lost film. No complete copies are known to exist in any film archives or private collections. Only fragments, still photographs, and the film's intertitles survive in various archives including the Library of Congress and the Paramount archive. The loss of this film is particularly significant as it represents the first screen adaptation of Molnár's popular play and an early example of Dimitri Buchowetzki's American work. The film's disappearance reflects the tragic loss of approximately 75% of American silent films due to nitrate decomposition, studio neglect, and lack of preservation efforts in the early decades of cinema.