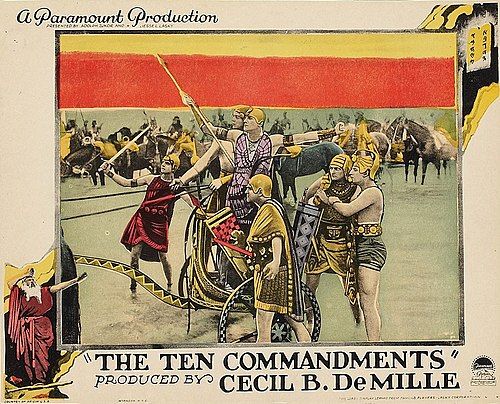

The Ten Commandments

"The Greatest Event in the History of Motion Pictures"

Plot

Cecil B. DeMille's 1923 epic masterpiece unfolds in two distinct parts. The first segment vividly portrays the biblical story of Moses (Theodore Roberts), from his birth and adoption by Pharaoh's daughter to his divine calling to lead the Hebrew slaves out of Egypt. The narrative follows Moses confronting Pharaoh Rameses (Charles De Rochefort), witnessing the ten plagues, parting the Red Sea, and ascending Mount Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments, only to find his people worshipping a golden calf upon his return. The second part transitions to a modern-day (1920s) San Francisco setting, demonstrating the commandments' relevance through the story of two brothers, carpenter John McTavish and corrupt contractor Dan McTavish, who are rivals for the affection of Mary Leigh (Estelle Taylor). When John discovers that Dan has used inferior materials to construct a cathedral, their moral conflict illustrates the enduring power of the commandments in contemporary life, culminating in a dramatic resolution that reinforces the film's central message about divine law versus human temptation.

About the Production

The film featured one of the largest sets ever constructed in Hollywood history, with the Egyptian city spanning 12 acres and including 21 sphinxes weighing 5 tons each. The parting of the Red Sea sequence was filmed by pouring 300,000 gallons of water through a specially constructed dam in the Guadalupe Dunes. Over 2,500 actors and 3,000 animals were employed for the biblical sequences. The modern story was filmed in color using the early Technicolor process for its opening prologue, making it one of the first films to incorporate color sequences.

Historical Background

The film emerged during the Roaring Twenties, a period of significant social change and technological advancement in America. The 1920s saw a resurgence of religious fundamentalism as a reaction against the perceived moral decay of the Jazz Age, culminating in the 1925 Scopes Trial over the teaching of evolution. DeMille's film tapped into this cultural tension by presenting biblical stories with unprecedented spectacle while simultaneously addressing contemporary moral issues. The film's production coincided with Hollywood's transition from short films to feature-length epics, as studios competed to create increasingly elaborate productions that would attract audiences away from the growing popularity of radio. The film's massive budget and scale reflected the industry's confidence in cinema's future as a dominant cultural medium. Additionally, the film's release came just four years before the introduction of sound in motion pictures, making it one of the last great silent epics and representing the pinnacle of silent film technical achievement.

Why This Film Matters

'The Ten Commandments' revolutionized the biblical epic genre and established the template for all subsequent religious films in Hollywood. Its dual narrative structure, combining biblical and contemporary stories, created a new cinematic language for exploring moral themes. The film's unprecedented success proved that religious content could be commercially viable on a massive scale, encouraging studios to invest in other biblical productions. Its technical achievements, particularly the special effects used for the plagues and the parting of the Red Sea, pushed the boundaries of what was possible in silent cinema. The film also helped establish Cecil B. DeMille as Hollywood's master of the epic spectacle, a reputation that would define his career. The movie's emphasis on moral values and its direct engagement with religious themes reflected and influenced American cultural attitudes toward faith and cinema. Its preservation of the Ten Commandments as a central moral framework resonated with audiences during a period of rapid social change and continues to influence how biblical stories are adapted for the screen.

Making Of

The production of 'The Ten Commandments' was an undertaking of unprecedented scale in 1923. Cecil B. DeMille, determined to create a film that would elevate cinema to an art form comparable to classical theater, spent months in pre-production planning. The Egyptian set was constructed in the remote Guadalupe Dunes of California, requiring workers to build a temporary town to house the cast and crew. The famous parting of the Red Sea sequence was achieved through a combination of practical effects: two enormous tanks of water were released simultaneously through a specially constructed channel, creating the illusion of water walls. The production faced numerous challenges, including extreme weather conditions in the desert location, the death of several animals during filming, and the technical difficulties of coordinating thousands of extras. DeMille's meticulous attention to detail extended to the costumes, which were based on extensive research of ancient Egyptian art and artifacts. The modern segment was filmed concurrently with the biblical sequences, creating a unique dual narrative structure that was revolutionary for its time.

Visual Style

The film's cinematography, led by Bert Glennon, was groundbreaking for its time and featured innovative techniques that would influence filmmaking for decades. The biblical sequences employed dramatic lighting and shadow effects to create a sense of divine presence and supernatural power. The parting of the Red Sea sequence used multiple camera angles and innovative perspectives to enhance the spectacle, including shots from above to capture the massive scale of the effect. The cinematography contrasted the warm, golden tones of the Egyptian sequences with the cooler, more naturalistic lighting of the modern story, visually reinforcing the film's dual narrative structure. The use of forced perspective and miniature models created the illusion of massive structures and vast landscapes. The film also featured early examples of camera movement, including slow zooms and tracking shots that were technically challenging in the silent era. The color prologue sequence, while brief, demonstrated the potential of color cinematography for enhancing narrative impact.

Innovations

The film pioneered numerous technical innovations that would become standard in later film productions. The special effects team, led by Roy Pomeroy, developed groundbreaking techniques for the biblical plagues, including the use of double exposure, matte paintings, and miniature models. The parting of the Red Sea sequence remains one of the most impressive technical achievements of silent cinema, combining practical water effects with carefully timed editing to create a seamless illusion. The production utilized the largest set ever built at the time, covering 12 acres and featuring structures that were fully functional for filming. The film's use of the early two-strip Technicolor process for its opening prologue represented one of the first successful integrations of color into a feature-length narrative. The production also developed innovative techniques for crowd control and coordination, using signal flags and horn blasts to direct thousands of extras during large-scale scenes. The film's editing, particularly the cross-cutting between the biblical and modern stories, was considered revolutionary for its time and influenced narrative techniques in subsequent films.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Ten Commandments' was accompanied by musical scores performed live in theaters during its original run. The film's official score was composed by Hugo Riesenfeld, one of the era's most prominent film composers, who created a comprehensive musical program that synchronized with the on-screen action. The score incorporated classical pieces, original compositions, and popular hymns to enhance the emotional impact of key scenes. For the biblical sequences, Riesenfeld used dramatic, orchestral arrangements with brass and percussion to create a sense of grandeur and divine intervention. The modern story featured more contemporary musical themes, including popular songs of the 1920s. The score was published for theater orchestras and included detailed cues for different-sized ensembles, ensuring consistent musical accompaniment across various venues. Modern restorations of the film have featured newly composed scores by contemporary silent film musicians, including organ and orchestral arrangements that attempt to recreate the original theatrical experience.

Famous Quotes

The law of God is written not in tablets of stone, but in the hearts of men.

Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

Where there is no vision, the people perish.

The blood of the lamb shall be your salvation.

What does it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his soul?

Memorable Scenes

- The parting of the Red Sea sequence, where massive walls of water dramatically part to allow the Hebrews to cross on dry land, remains one of cinema's most iconic special effects achievements.

- The Golden Calf sequence, featuring thousands of extras in wild revelry, contrasted with Moses's righteous anger upon descending from Mount Sinai.

- The plague sequences, particularly the darkness over Egypt and the death of the firstborn, showcased innovative special effects techniques.

- The opening Technicolor prologue, depicting the creation of the tablets, was one of the earliest uses of color in narrative cinema.

- The modern San Francisco cathedral collapse scene, which dramatically illustrates the consequences of corruption and moral failure.

Did You Know?

- The massive Egyptian set was left standing in the Guadalupe Dunes for decades and became a local tourist attraction until it was gradually reclaimed by the sand dunes, with archaeologists still discovering pieces today.

- This was the most expensive film ever made at the time of its release, with a budget that exceeded $1.4 million.

- Director Cecil B. DeMille was so committed to authenticity that he consulted biblical scholars and historians, though he took artistic liberties for dramatic effect.

- The film's success directly led to DeMille's 1956 remake, which he considered his magnum opus.

- The color prologue sequence was one of the earliest uses of Technicolor in a feature film, though the rest of the movie was in black and white.

- Over 5,000 extras were employed during the filming of the Exodus sequence, making it one of the largest crowd scenes in silent cinema.

- The film's premiere was held at the Criterion Theatre in New York City with tickets costing an unprecedented $5 each.

- DeMille reportedly experienced a religious conversion during production and became a devout Christian for the remainder of his life.

- The special effects team used Jell-O to create the appearance of the plague of locusts, as it held its shape well under the hot studio lights.

- The original film negative was destroyed in a 1930s vault fire, but copies survived and have been preserved by various film archives.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics hailed the film as a masterpiece of cinematic art and a triumph of the medium. The New York Times praised it as 'the most impressive and important picture yet produced by the American film industry,' while Variety declared it 'a picture that will stand for all time as a monument to the art of motion pictures.' Critics particularly lauded the film's spectacular effects, ambitious scope, and DeMille's direction. The moral message of the film was widely praised as wholesome and uplifting, with many reviewers noting its potential to elevate cinema's cultural status. Modern critics and film historians continue to regard the 1923 version as a landmark achievement in silent cinema, often comparing it favorably to the 1956 remake for its innovative techniques and raw visual power. The film is frequently cited in film studies as a crucial example of early American epic filmmaking and remains a subject of scholarly analysis for its religious themes and technical innovations.

What Audiences Thought

The film was an enormous commercial success, becoming the highest-grossing film of 1923 and one of the most profitable films of the silent era. Audiences were captivated by its spectacular effects and grand scale, with many attending multiple viewings to fully appreciate the visual details. The film's moral message resonated strongly with 1920s audiences, who were navigating the cultural tensions between traditional values and modern lifestyles. Contemporary reports described emotional reactions from viewers, particularly during religious scenes, with some audience members reportedly weeping during the Exodus sequence. The film's popularity extended beyond traditional movie theaters, with special screenings organized by churches and religious organizations across the country. Its success spawned numerous imitations and established a market for religious epics that would continue for decades. The film's enduring popularity is evidenced by its continued screenings at revival houses and film festivals, where it continues to draw audiences interested in classic cinema and religious history.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Award (Honorary) for Unique and Artistic Production - 1929 (retrospective award for 1927/28 season)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Bible (Book of Exodus)

- D.W. Griffith's 'Intolerance' (1916) - for its epic scale and dual narrative structure

- Italian historical epics such as 'Cabiria' (1914)

- Victor Hugo's 'Les Misérables' - for themes of moral redemption

- Contemporary religious revivals and fundamentalist movements

This Film Influenced

- The Ten Commandments (1956) - DeMille's own remake

- Ben-Hur (1925 and 1959)

- The King of Kings (1927)

- Samson and Delilah (1949)

- The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965)

- The Prince of Egypt (1998)

- Noah (2014)

- Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in various film archives including the Library of Congress, the UCLA Film and Television Archive, and the Museum of Modern Art. While the original camera negative was lost in a vault fire in the 1930s, complete prints survive and have been restored multiple times. The most recent restoration was completed in 2010 by Paramount Pictures, featuring newly color-tinted sequences based on original documentation. The film has been selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. Some of the Technicolor footage remains lost, but the majority of the film exists in high-quality prints that have been digitally remastered for home video release.