The Wedding March

"Love or Money? The Eternal Conflict of the Heart!"

Plot

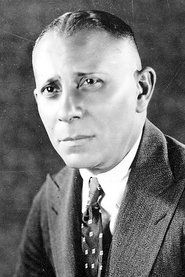

Prince Nikki, an impoverished Austrian aristocrat played by Erich von Stroheim, falls deeply in love with Mitzi, a beautiful innkeeper's daughter portrayed by Fay Wray, while stationed in a small Tyrolean village. Despite their genuine connection, Nikki's family pressures him to marry into wealth to restore their dwindling fortune, specifically targeting Cecilia, the daughter of a wealthy prince. The film follows Nikki's internal struggle between his heart's desire and his duty to family and social position, set against the backdrop of pre-World War I Vienna's aristocratic society. As the wedding approaches, Nikki must choose between true love and financial security, leading to tragic consequences that explore the destructive nature of class divisions and social expectations. The narrative culminates in a powerful examination of sacrifice, regret, and the irreversible consequences of choices made under social pressure.

About the Production

The production was notorious for von Stroheim's perfectionism and attention to detail, with authentic period costumes and sets that drove costs skyward. The original cut ran approximately 4 hours, but Paramount forced von Stroheim to edit it down significantly. The production took over a year to complete, with von Stroheim insisting on authentic Austrian details and refusing to compromise his artistic vision despite studio pressure.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the height of the Jazz Age, a period of dramatic social change and economic prosperity in America, yet it looks back nostalgically at the dying aristocratic world of pre-World War I Europe. This reflection on the past was particularly poignant for audiences in the 1920s who had witnessed the collapse of European monarchies and the old social order. Von Stroheim, an Austrian immigrant who had served in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I, brought authentic insight to the portrayal of aristocratic decline. The film's themes of duty versus personal desire resonated strongly in an era when traditional social structures were being challenged by modern values. The late 1920s also marked the transition from silent films to talkies, making 'The Wedding March' part of the final flowering of silent cinema's artistic ambitions.

Why This Film Matters

'The Wedding March' represents the pinnacle of silent cinema's artistic achievements and stands as a testament to Erich von Stroheim's uncompromising artistic vision. The film's exploration of class conflict, social duty, and personal sacrifice influenced generations of filmmakers and helped establish the melodrama as a serious cinematic art form. Its sophisticated visual storytelling techniques demonstrated how silent films could convey complex emotional and psychological depth without dialogue. The movie's portrayal of European aristocracy's decline captured the nostalgia and melancholy of a generation that had witnessed the transformation of the old world order. The film's troubled production history and subsequent partial loss have made it a legendary example of the artistic struggles between creative visionaries and commercial studios, a theme that continues to resonate in Hollywood today.

Making Of

The production of 'The Wedding March' became legendary in Hollywood for its excess and von Stroheim's obsessive attention to detail. The director, known as 'the greatest director who never completed a film,' spent months researching Austrian aristocracy and insisted on absolute authenticity in every aspect of production. He built enormous, detailed sets including a full-scale replica of a Viennese palace and imported authentic furnishings from Europe. The cast and crew suffered through von Stroheim's demanding methods, with some scenes requiring dozens of takes to achieve his vision. Fay Wray later recounted how von Stroheim made her wear authentic Austrian peasant shoes that were too small, causing her feet to bleed during filming. The production's budget spiraled out of control, leading to intense conflicts with Paramount executives who eventually took control of the final cut, much to von Stroheim's dismay. The director's perfectionism extended to requiring extras to wear authentic period underwear, even though it would never be seen on camera.

Visual Style

The cinematography, primarily by Ben Reynolds and William H. Daniels, was groundbreaking for its use of deep focus and complex tracking shots. The film employed sophisticated lighting techniques to create atmospheric effects, particularly in the Vienna palace sequences where light and shadow were used to emphasize the psychological states of the characters. The camera work included innovative crane shots and elaborate tracking movements that were technically advanced for the period. The visual style combined realistic detail with expressionistic lighting, creating a dreamlike quality that enhanced the film's romantic and tragic elements. The cinematography particularly excelled in crowd scenes, where the camera moved fluidly through hundreds of extras to create a sense of immersive reality.

Innovations

The film was notable for its innovative use of the newly developed panchromatic film stock, which allowed for more natural skin tones and greater detail in both shadows and highlights. The production pioneered techniques for shooting large crowd scenes, using multiple cameras and carefully choreographed movements to create complex visual compositions. The set design included working mechanical devices and authentic period architecture that set new standards for realism in film production. The film also experimented with early color processes for certain sequences, though these elements have been lost in most surviving versions. The makeup techniques developed for the film, particularly for aging the characters, were considered revolutionary at the time.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Wedding March' was accompanied by live orchestral music during its theatrical run. The original score was composed by Josiah Zuro, who created a lush romantic soundtrack that incorporated Austrian waltzes and classical pieces appropriate to the film's setting. The musical accompaniment was particularly important during the wedding sequence, where Schubert's 'Ave Maria' and Wagner's wedding march from 'Lohengrin' were used to dramatic effect. The score emphasized the film's emotional contrasts between the aristocratic world and the simple life of the innkeeper's daughter. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the spirit of the original while taking advantage of contemporary musical resources.

Famous Quotes

'Love is the only thing that makes life worth living' - Prince Nikki

'Duty is heavier than a mountain, death lighter than a feather' - Intertitle

'In Vienna, everything is beautiful except the truth' - Opening intertitle

'We are all prisoners of our birth' - Prince Nikki

'Some hearts are broken before they learn to beat' - Intertitle

Memorable Scenes

- The elaborate wedding march sequence with hundreds of extras in authentic period costumes, representing the pinnacle of the film's visual spectacle

- The intimate scenes between Prince Nikki and Mitzi in the Tyrolean inn, showcasing the chemistry between von Stroheim and Wray

- The masquerade ball in Vienna where the social contrasts are most dramatically displayed

- The final confrontation scene where Prince Nikki must choose between love and money

- The opening military procession establishing the film's historical setting and visual style

Did You Know?

- The film was originally intended to be shown in two parts, but Paramount released only the first part theatrically

- Fay Wray considered this role her breakthrough performance, leading to her casting in 'King Kong' (1933)

- Von Stroheim spent $250,000 building an elaborate replica of Vienna's Prater amusement park for the film

- The director insisted on authentic Austrian military uniforms, importing actual uniforms from Vienna

- Only about half of von Stroheim's original cut survives today, with the rest considered lost

- The film's excessive budget and von Stroheim's uncompromising vision led to his reputation as 'the man you love to hate' in Hollywood

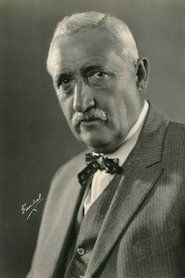

- George Fawcett, who played Prince Nikki's father, was actually 13 years younger than von Stroheim

- The wedding march sequence took weeks to film due to von Stroheim's insistence on perfect crowd choreography

- The film was shot in early Technicolor for certain sequences, though most versions today exist only in black and white

- Von Stroheim used over 3,000 extras for the crowd scenes, an unprecedented number for the time

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics were divided on the film, with many praising von Stroheim's artistic vision and technical mastery while criticizing its excessive length and self-indulgence. The New York Times called it 'a magnificent spectacle' but noted 'its length tries the patience.' Modern critics have reassessed the film more favorably, with many considering it a misunderstood masterpiece of silent cinema. Film historian Kevin Brownlow described it as 'one of the most beautiful and moving films ever made' while acknowledging its tragic incompleteness. The film's reputation has grown over time, with contemporary scholars praising its sophisticated visual style, psychological depth, and critique of class structure. The surviving portions are now studied as examples of silent cinema's highest artistic achievements, despite their fragmented nature.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception was lukewarm, with many finding the film's pacing too slow and its themes too heavy for entertainment. The film's commercial failure was attributed to its length and the public's growing preference for lighter fare during the transition to sound films. However, among film enthusiasts and artistic circles, the movie developed a cult following even in its time. Modern audiences who have seen the surviving fragments often express fascination with its visual beauty and emotional power, despite the incomplete nature of what remains. The film's reputation has benefited from retrospective screenings at film festivals and revival houses, where it is now appreciated as a masterpiece of silent cinema that was ahead of its time.

Awards & Recognition

- National Film Registry - Selected for preservation in 1996 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance

Film Connections

Influenced By

- European literature of the late 19th century

- Austrian operatic tradition

- The works of Arthur Schnitzler

- Viennese café culture

- German Expressionist cinema

- The decline of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

- Von Stroheim's own military experience

This Film Influenced

- The Merry Widow (1934)

- Grand Hotel (1932)

- The Great Waltz (1938)

- The Sound of Music (1965)

- The Last Emperor (1987)

- The Age of Innocence (1993)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film exists in a truncated form with approximately half of von Stroheim's original cut lost. The surviving elements are preserved at the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. A restored version combining various surviving elements was released by Kino International, but significant portions remain missing. The film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 1996. Efforts continue to locate missing footage in archives and private collections worldwide, though the chances of finding a complete version grow increasingly remote.