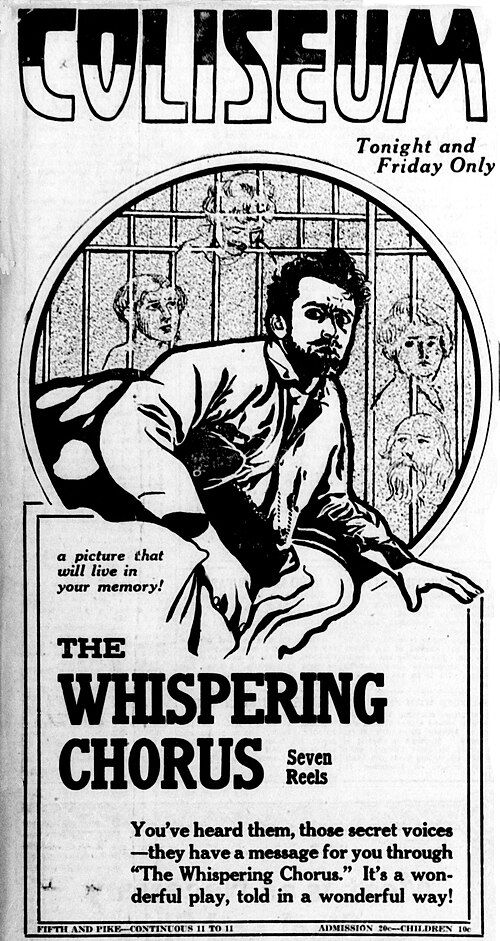

The Whispering Chorus

"A story of a man who murdered himself to escape from himself"

Plot

John Trimble, a weak-willed accountant, embezzles $5,000 from his employer and, unable to face the consequences, plots an elaborate escape with a criminal associate. They murder a drifter and mutilate the body beyond recognition, burying it in Trimble's place to make everyone believe he has died. Trimble assumes a new identity as John Fielding and moves to another town, where he eventually becomes a respected citizen and falls in love with a woman named Jane. Years later, when the body is discovered, Trimble is arrested and charged with his own murder, leading to a sensational trial. During the proceedings, his mother attends and, upon seeing him, dies from the shock, but not before extracting a promise that he maintain his new identity since his former wife has remarried the Governor and is expecting a child.

About the Production

The film was one of Cecil B. DeMille's most sophisticated early works, featuring innovative use of split-screen effects to show the protagonist's internal conflict. The production faced challenges with the graphic nature of some scenes, particularly the murder sequence, which was controversial for its time. DeMille insisted on realistic makeup effects for the mutilated body scene, pushing the boundaries of what was acceptable in 1918 cinema.

Historical Background

The Whispering Chorus was produced during the final year of World War I, a time when American society was grappling with questions of morality, responsibility, and redemption. The film reflected the growing sophistication of American cinema as it moved away from simple melodramas toward more complex psychological narratives. 1918 was also a period of significant change in Hollywood, with the studio system becoming more established and directors like DeMille gaining unprecedented creative control. The film's themes of guilt and moral responsibility resonated with audiences dealing with the aftermath of war and the social upheavals of the era. The production took place during the Spanish Flu pandemic, which affected filming schedules and may have contributed to the film's dark, somber tone.

Why This Film Matters

The Whispering Chorus represents a pivotal moment in American cinema's transition toward psychological complexity and moral ambiguity. Its innovative visual techniques, particularly the use of split-screen to represent internal conflict, influenced countless subsequent films. The movie helped establish the template for the 'guilt-ridden protagonist' narrative that would become a staple of film noir decades later. Its exploration of identity and the consequences of moral failure resonated with audiences and critics alike, elevating the cultural perception of movies from mere entertainment to serious art. The film's success demonstrated that audiences were ready for more sophisticated storytelling, paving the way for the complex narratives of the 1920s and beyond.

Making Of

Cecil B. DeMille was deeply invested in this project, seeing it as an opportunity to explore complex moral themes beyond the simple melodramas common at the time. The production was notably ambitious for its budget, with DeMille insisting on elaborate sets for the courtroom scenes and realistic location shooting. Raymond Hatton underwent a significant transformation for his role, losing weight and adopting a hunched posture to convey his character's moral decay. The famous split-screen sequences required innovative camera techniques and multiple exposures, which were technically challenging in 1918. DeMille worked closely with his cinematographer to develop new methods for visualizing the 'whispering chorus' effect, using superimposed images and double exposures. The film's controversial content, particularly the murder scene, required careful negotiation with censors of the time.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Alvin Wyckoff was groundbreaking for its time, featuring innovative use of split-screen to visualize the protagonist's internal conflict. The film employed multiple exposure techniques to create the 'whispering chorus' effect, showing multiple versions of the character's conscience simultaneously. Wyckoff used dramatic lighting contrasts to emphasize the moral ambiguity of the story, with deep shadows representing the character's guilt. The courtroom sequences featured unusually mobile camera work for 1918, with tracking shots that added tension and realism to the proceedings. The visual style combined realistic settings with expressionistic lighting to create a dreamlike quality that reflected the psychological nature of the narrative.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations that would become standard in cinema. Most notably, it featured some of the earliest uses of split-screen to show simultaneous action and internal thoughts. The production developed new techniques for makeup effects, particularly for the mutilated body sequence, which were remarkably realistic for the time. The film also experimented with camera movement, using tracking shots in the courtroom scenes that were technically demanding in 1918. The multiple exposure techniques used to create the 'whispering chorus' effect required precise timing and coordination between the camera and performers.

Music

As a silent film, The Whispering Chorus was accompanied by live musical performances during its original theatrical run. The score was composed by William Furst, who created a complex orchestral arrangement that emphasized the film's psychological tension. The music featured recurring leitmotifs for different characters and emotional states, particularly a haunting melody that represented the 'whispering chorus' of conscience. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the emotional impact of the original music while using contemporary orchestration techniques.

Famous Quotes

The whispers of conscience are louder than any voice of reason.

To escape yourself, you must first destroy yourself.

Sometimes the greatest crime is not what we do, but who we become.

In the courtroom of life, we are all judged by the jury of our own conscience.

Memorable Scenes

- The split-screen sequence showing John Trimble's internal conflict as the 'whispering chorus' of his conscience surrounds him

- The murder scene where the drifter is killed and his body mutilated to stand in for Trimble

- The dramatic courtroom revelation where Trimble is confronted with evidence of his own 'death'

- The emotional deathbed scene where Trimble's mother extracts his promise to maintain his new identity

Did You Know?

- The film was considered lost for decades until a complete print was discovered in the 1970s in the Netherlands.

- Cecil B. DeMille considered this one of his most personal films, dealing with themes of guilt and redemption that would recur throughout his career.

- The title refers to the 'whispering chorus' of voices that represents the protagonist's conscience throughout the film.

- Raymond Hatton, who played John Trimble, was one of DeMille's favorite character actors and appeared in over 20 of his films.

- The film's innovative use of split-screen to show the character's inner thoughts was groundbreaking for 1918.

- The courtroom scene was filmed in a single continuous take, a technical feat for the time.

- The film was one of the first to use the concept of a character being tried for his own murder.

- Kathlyn Williams, who played Jane, was a major star of the 1910s and was known as 'The Biograph Girl' before this role.

- The film's success helped establish DeMille as one of Hollywood's premier directors of moral dramas.

- The mutilated body effects were created by early makeup pioneer George Westmore.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised The Whispering Chorus for its bold storytelling and technical innovations. The New York Times called it 'a masterpiece of psychological drama' and specifically noted DeMille's 'daring use of new cinematic techniques to explore the human soul.' Variety praised Raymond Hatton's performance as 'a revelation of depth and subtlety rarely seen on the silver screen.' Modern critics have rediscovered the film as an important precursor to film noir, with many noting its sophisticated treatment of guilt and redemption. The film is now recognized as one of DeMille's most artistically ambitious works, standing in contrast to his later, more spectacular epics.

What Audiences Thought

The film was a commercial success upon its release, drawing large audiences to its multiple theatrical runs. Viewers were particularly struck by the innovative visual effects and the compelling moral dilemma at the story's core. Many contemporary newspaper accounts reported audiences leaving theaters in deep discussion about the film's ethical questions. The film's reputation grew over time, with it being remembered as one of the most thought-provoking dramas of the silent era. Modern audiences who have had the opportunity to see restored versions often express surprise at the film's sophistication and emotional depth, challenging assumptions about the simplicity of early cinema.

Awards & Recognition

- Special Commendation for Moral Significance - National Board of Review (1918)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Dostoevsky's 'Crime and Punishment'

- German Expressionist cinema

- Contemporary American morality plays

This Film Influenced

- The Man Who Cheated Himself

- The Wrong Man

- Film noir of the 1940s and 1950s

- Psychological thrillers of the 1960s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for many years but a complete 35mm print was discovered in the Netherlands Film Archive in the 1970s. This print has since been preserved and restored by film archives including the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. The restored version maintains most of the original's visual quality, though some deterioration is evident in certain scenes. The film is now considered well-preserved compared to many other silent-era features.