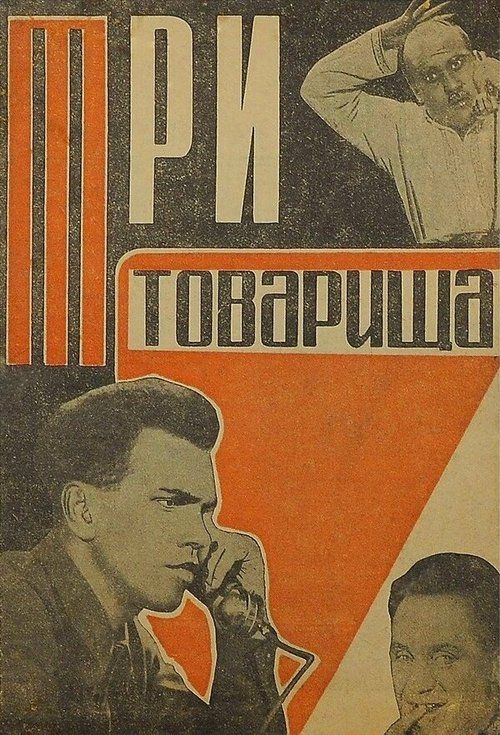

Three Comrades

"The bonds of friendship tested by revolution and progress"

Plot

The story follows Zaitsev, a new construction manager who arrives in a small Soviet town with ambitious plans for rapid industrial expansion. He reconnects with his former Red Army comrades: Glinka, who now directs the local paper factory, and Latsis, who heads the timber rafting operation. Despite their shared revolutionary past, Zaitsev's aggressive modernization approach and his association with opportunistic sycophants create tension with his old friends. As Zaitsev pushes forward with his expansion plans, revelations about his methods and character come to light, exposing the conflict between revolutionary ideals and the practical challenges of Soviet industrialization. Ultimately, Zaitsev is forced to leave the town, leaving his comrades to continue their work in building socialism through more measured means.

About the Production

The film was produced during the height of Stalin's Five-Year Plans, reflecting the Soviet emphasis on industrialization and socialist construction. Director Semyon Timoshenko was one of the prominent figures in Soviet cinema during this period, known for his ability to blend entertainment with ideological messaging. The production faced typical challenges of 1930s Soviet filmmaking, including limited resources and strict ideological oversight from state authorities.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a critical period in Soviet history, the mid-1930s, when Stalin's industrialization drive was in full swing. The Five-Year Plans were transforming the Soviet Union from an agricultural society into an industrial powerhouse, often at tremendous human cost. This era also saw the establishment of socialist realism as the official artistic doctrine, requiring all art to be realistic in form and socialist in content. The film's focus on industrial construction, revolutionary friendship, and ideological purity perfectly reflected the priorities and tensions of this period. The Great Purge would begin in 1936, making this film one of the last works of relative artistic freedom before the most repressive period of Stalin's rule.

Why This Film Matters

Three Comrades stands as an important example of how Soviet cinema navigated the complex demands of entertainment and ideology during the Stalin era. The film contributed to the development of the socialist realist style in cinema, balancing dramatic storytelling with didactic elements. It helped establish the template for films about Soviet industrial heroes and the importance of collective work over individual ambition. The movie's exploration of friendship tested by ideological progress resonated with audiences who had experienced the rapid changes of Soviet modernization. It also demonstrated how Soviet cinema could address complex social issues within the constraints of state-approved narratives, influencing subsequent generations of Soviet filmmakers.

Making Of

The production took place at Lenfilm, one of the Soviet Union's most prestigious film studios. Director Semyon Timoshenko, known for his efficient working methods, completed the film relatively quickly by Soviet standards. The cast included several actors who had served in the Red Army, adding authenticity to their portrayals of former comrades. The factory scenes were shot in actual working paper mills, requiring careful coordination with industrial production schedules. The script underwent multiple revisions to satisfy both artistic and ideological requirements from state film authorities. The film's balance of entertainment value with socialist realist principles made it a model example of how Soviet cinema was supposed to function during the Stalin era.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Vladimir Rapoport employed both documentary-style realism for the industrial sequences and more romanticized lighting for the dramatic scenes. The camera work emphasized the scale of Soviet industrial achievement through sweeping shots of factories and construction sites, while maintaining an intimate focus on the characters' emotional journeys. The visual contrast between the old town and the new industrial construction symbolized the transformation of Soviet society. The use of location shooting in actual factories added authenticity to the production scenes, a technique that was still relatively innovative in Soviet cinema of the 1930s.

Innovations

The film was notable for its extensive use of location shooting in working industrial facilities, which presented significant technical challenges for the 1930s Soviet film industry. The production team developed new techniques for filming in noisy factory environments while maintaining clear audio recording. The cinematography employed innovative camera movements to capture the scale of industrial operations, including crane shots that were technically advanced for the time. The film's editing style balanced the rhythmic pace of industrial sequences with more measured pacing for dramatic scenes, demonstrating sophisticated understanding of film rhythm. These technical achievements helped establish new standards for Soviet industrial filmmaking.

Music

The musical score was composed by Dmitri Kabalevsky, who would later become one of the Soviet Union's most celebrated composers. The soundtrack combines heroic orchestral themes for the industrial sequences with more intimate melodies for the personal drama scenes. The music incorporates elements of Soviet folk songs and revolutionary anthems, grounding the story in Soviet cultural traditions. The score was particularly praised for its ability to enhance the emotional impact of the friendship narrative without overwhelming the ideological content. Kabalevsky's work on this film helped establish his reputation as a composer who could successfully serve both artistic and state requirements.

Did You Know?

- Director Semyon Timoshenko was a veteran of both the Russian Civil War and early Soviet cinema, bringing authentic experience to the military comradery depicted

- The film was released during the second Five-Year Plan (1933-1937), a period of intense industrialization in the USSR

- Mikhail Zharov, who played one of the leads, would later become a People's Artist of the USSR, the highest artistic honor in the Soviet Union

- The paper factory setting was chosen deliberately to showcase Soviet industrial achievements in a sector important for education and propaganda

- The film's themes of friendship tested by ideological differences reflected real tensions in Soviet society during the 1930s

- Timoshenko was known for his ability to create commercially successful films that still satisfied Soviet ideological requirements

- The character of Zaitsev represents the 'New Soviet Man' archetype, though with flaws that make the story more complex

- The film was one of several in 1935 that explored the theme of revolutionary friendship in the context of socialist construction

- Cinematographer Vladimir Rapoport would later work on several classic Soviet war films

- The film's release coincided with the 18th anniversary of the October Revolution, making its themes particularly timely

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film for its successful blend of entertainment value with ideological messaging. Pravda, the official newspaper of the Communist Party, commended the film for showing 'the correct path of socialist construction through the lens of human relationships.' Critics particularly appreciated the performances of the three leads and the authentic depiction of industrial life. In later Soviet film criticism, the film was recognized as a classic example of 1930s socialist realist cinema. Modern film scholars have re-evaluated the work as a sophisticated example of how filmmakers worked within and sometimes subtly subverted the constraints of the Soviet system.

What Audiences Thought

The film was popular with Soviet audiences upon its release, particularly among workers and industrial managers who could relate to its setting and themes. Audiences appreciated the emotional core of the friendship story while also responding to the film's optimistic vision of Soviet progress. The movie ran successfully in theaters across the Soviet Union for several months, an unusually long run for the period. Veterans of the Civil War found particular resonance in the depiction of comradeship tested by new challenges. The film's success helped cement Semyon Timoshenko's reputation as one of Soviet cinema's most reliable directors.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize (Second Class) - 1936 (for outstanding achievement in Soviet cinema)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet socialist realist literature

- Works of Maxim Gorky

- Earlier Soviet industrial films like 'Turksib' (1929)

- The writings of Nikolai Ostrovsky

- Stalinist cultural doctrine

This Film Influenced

- The Great Citizen

- 1938

- The Radiant Path

- 1940

- The Return of Vasil Borykinov

- 1953

- The Chairman

- 1964

- Andrei Rublev

- 1966

- ],

- similarFilms

- The Height,1957,Communist,1957,Nine Days of One Year,1962,The Beginning,1970,Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears,1980,famousQuotes,In revolution, we were brothers in arms. In peace, we must be brothers in construction.,A factory is not just machines and paper, it's the future of our people.,Progress without principle is just another form of destruction.,True comradeship survives not only war, but peace as well.,The hardest battle is not against enemies, but against our own weaknesses.,memorableScenes,The emotional reunion scene where the three Red Army veterans meet again in the industrial town, their uniforms replaced by work clothes but their bond still evident,The tense confrontation in the paper factory director's office where ideological differences between old friends come to a head,The sequence showing the timber rafting operation, combining documentary-style realism with dramatic cinematography,The final departure scene where Zaitsev leaves the town, with his former comrades watching from the factory grounds,preservationStatus,The film has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond of Russia, the state film archive. A restored version was released in the 1970s as part of a Soviet classic cinema restoration project. The film exists in its complete form with good image and sound quality, though some minor deterioration is visible in certain sequences. Digital restoration was completed in 2015 as part of the 80th anniversary of Soviet cinema celebrations.,whereToWatch,Available in the Gosfilmofond digital archive,Occasionally screened at classic film festivals and retrospectives,Available through select academic film libraries specializing in Soviet cinema,Some versions available on specialized streaming platforms for classic world cinema