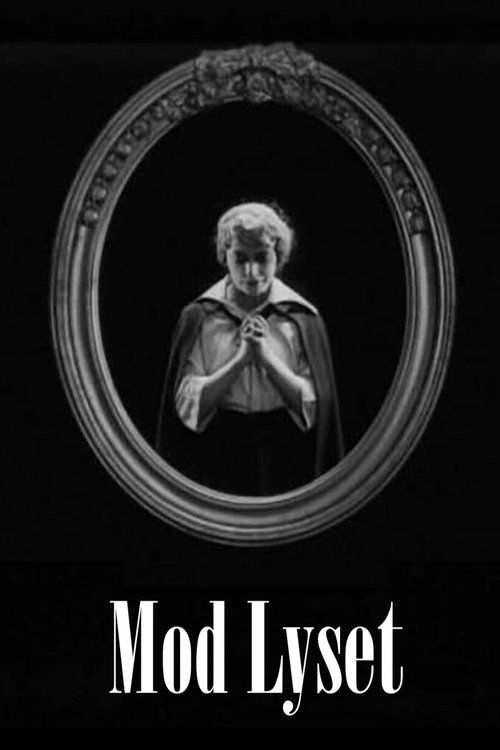

Towards the Light

Plot

Countess Ysabel is a wealthy young woman surrounded by numerous suitors vying for her affection and fortune. She becomes captivated by an elegant and adventurous baron who successfully wins her heart, yet she continues to toy with the emotions of other men, unable to commit fully to any single relationship. The consequences of her manipulative behavior become devastating when a young man, heartbroken by her rejection, takes his own life, bringing the weight of mortality into her privileged world. Simultaneously, the baron reveals a terrible secret that shatters Ysabel's perception of him and their relationship, forcing her to confront the reality of her choices. As her carefully constructed social world begins to crumble around her, Ysabel must face the moral and emotional consequences of her actions, leading her toward a path of redemption and self-discovery.

About the Production

The film was produced during the final years of Denmark's golden age of silent cinema, when Nordisk Film was still one of Europe's most influential production companies. The production utilized natural lighting techniques that were innovative for the time, particularly in scenes symbolizing the protagonist's journey 'toward the light.' The film was shot on location at several Danish estates that provided authentic settings for the aristocratic drama.

Historical Background

The film was produced in 1919, during the immediate aftermath of World War I, a period of profound social and cultural transformation across Europe. Denmark, though neutral during the war, experienced significant economic and social changes that influenced its cinema. The film reflects the era's growing interest in psychological realism and moral questioning, moving away from the more simplistic melodramas of earlier cinema. This period also saw the decline of Danish cinema's international dominance, as German and American industries gained prominence. The film's themes of redemption and moral consequences resonated with audiences grappling with the war's aftermath and seeking meaning in a changed world. The aristocratic setting and critique of privilege also reflected the growing social tensions that would eventually lead to greater democratization across European societies.

Why This Film Matters

'Towards the Light' represents a crucial transition point in European cinema, bridging the early melodramatic traditions with the more psychologically complex films of the 1920s. Asta Nielsen's performance in this film exemplifies the new naturalistic acting style that would influence generations of actors. The film's exploration of female agency and moral complexity was progressive for its time, offering a nuanced portrayal of a woman's journey from superficiality to self-awareness. The technical innovations in lighting and cinematography contributed to the visual language of cinema, particularly in using light as metaphor. The film also stands as a testament to Denmark's significant but often overlooked contribution to early cinema history, preserving the artistic achievements of the Nordic silent film tradition.

Making Of

The production of 'Towards the Light' took place during a challenging period for European cinema, following the devastation of World War I. Director Holger-Madsen, known for his meticulous attention to psychological detail, worked closely with Asta Nielsen to develop a character that embodied both the glamour and moral complexity of the post-war aristocracy. The filming required extensive location shooting at Danish manor houses, which presented logistical challenges given the limited transportation available in 1919. Nielsen, who had significant creative control, insisted on performing her own stunts and refused to use a body double for the emotionally demanding scenes. The film's lighting design was particularly innovative, with cinematographer Louis M. Sørensen employing techniques to create visual metaphors for the protagonist's journey from moral darkness toward enlightenment. The production faced financial constraints due to the post-war economic situation, but Nordisk Film's commitment to quality filmmaking ensured the project's completion with high production values.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Louis M. Sørensen employs innovative techniques for its time, particularly in its use of natural lighting and shadow to create psychological depth. The film features several scenes shot with dramatic backlighting to symbolize the protagonist's moral journey, with the lighting gradually becoming brighter as the story progresses toward redemption. Sørensen utilized moving camera shots that were relatively advanced for 1919, including tracking shots during emotional confrontation scenes. The composition frequently frames characters through architectural elements like doorways and windows, creating visual metaphors for their psychological states. The film's visual style balances the ornate settings of aristocratic life with intimate close-ups that capture nuanced emotional expressions, reflecting the transition from theatrical to cinematic acting styles.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations that were significant for 1919. The lighting design, particularly the use of chiaroscuro effects to represent moral states, was ahead of its time. The production employed multiple camera setups for complex scenes, allowing for more dynamic editing than was typical in Danish cinema of the period. The film's special effects, particularly in the suicide sequence, used innovative in-camera techniques rather than the more common post-production tricks. The makeup and costume design featured subtle aging effects that showed the psychological toll on the protagonist, a sophisticated approach for the era. The film also experimented with narrative pacing, using longer takes for emotional moments while maintaining a brisk overall rhythm that kept audiences engaged.

Music

As a silent film, 'Towards the Light' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical score would have been provided by a theater organist or small orchestra, using classical pieces and popular music of the era. The emotional scenes likely featured Romantic-era compositions by composers like Chopin or Brahms, while the more dramatic moments would have used Wagnerian selections. The film's Danish premiere probably included music by Danish composers, though specific documentation of the original musical accompaniment has been lost. Modern screenings of restored versions often feature newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the emotional tone and period authenticity of the original presentations.

Famous Quotes

The light we seek is not without, but within the soul we have long neglected

Every heart broken in vanity leaves a scar upon the breaker's own soul

In the dance of society, some lead while others merely follow the music of their own destruction

Secrets are like shadows - they grow longest when the light is furthest away

True nobility lies not in birth, but in the courage to face one's own darkness

Memorable Scenes

- The suicide sequence, filmed with innovative camera angles and lighting to create emotional impact without being gratuitous

- The baron's secret revelation scene, shot in one continuous take that builds tension through performance and camera movement

- The final scene where Ysabel walks toward literal and metaphorical light, using natural lighting to symbolize her redemption

- The ballroom sequence where multiple suitors compete for Ysabel's attention, showcasing the film's impressive production design and choreography

- The intimate confrontation between Ysabel and the baron after the suicide, featuring nuanced performances and subtle camera work

Did You Know?

- Asta Nielsen was one of the highest-paid and most famous actresses in Europe during this period, commanding unprecedented creative control over her films

- The film's original Danish title 'Mod Lyset' literally translates to 'Toward the Light,' reflecting its themes of redemption and moral clarity

- Director Holger-Madsen was a medical doctor before turning to filmmaking, which influenced his focus on psychological realism in his films

- The film was one of the last major Danish productions before the country's film industry was largely overshadowed by German cinema in the 1920s

- Nordisk Film, the production company, was founded in 1906 and is still operational today, making it the world's oldest continuously operating film studio

- The suicide scene was considered controversial for its time and was censored or cut in several countries

- Asta Nielsen's distinctive acting style, which emphasized subtle facial expressions and natural movement, was revolutionary for silent cinema

- The film's intertitles were written by acclaimed Danish screenwriter Laurids Skands

- The baron's secret revelation scene was shot in one continuous take, a technical achievement for 1919

- The film was exported to over 20 countries, helping maintain Denmark's cultural influence during the post-war period

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its psychological depth and Asta Nielsen's nuanced performance, with Danish newspapers calling it 'a masterpiece of emotional truth.' German critics particularly highlighted the film's technical achievements in lighting and composition. The film received mixed reviews in France, where some critics found the moral themes too heavy-handed. Modern film historians have reassessed the work as an important example of late Danish silent cinema, noting its sophisticated narrative structure and visual storytelling. The film is now recognized as a significant work in both Nielsen's filmography and in the broader context of European silent cinema, with particular appreciation for its innovative use of light as symbolic element.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by contemporary audiences, particularly in Denmark and Germany, where it enjoyed successful theatrical runs. Viewers responded strongly to Nielsen's performance and the film's emotional intensity. The controversial suicide scene generated significant discussion and debate among audiences, with some finding it too disturbing while others praised its realism. The film's themes of redemption resonated with post-war audiences seeking moral clarity and hope. Box office records indicate the film was commercially successful, though not as profitable as some of Nielsen's earlier works. Modern audiences who have seen the film through rare screenings and archives often comment on its surprisingly modern sensibilities and psychological sophistication.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The psychological dramas of August Blom

- Swedish naturalist cinema of Victor Sjöström

- German expressionist visual techniques

- 19th-century Danish literature

- The moral plays of Henrik Ibsen

This Film Influenced

- Later psychological dramas of the 1920s

- German films about moral redemption

- Danish cinema of the 1920s

- Films featuring complex female protagonists

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is partially preserved with some scenes missing or damaged. The Danish Film Institute holds an incomplete copy of the original nitrate print, with approximately 70% of the film surviving. Several key sequences exist in good condition, while others are available only in fragmented form. Restoration efforts have been ongoing, with the most recent digital restoration completed in 2018 combining materials from multiple archives. The missing intertitles have been reconstructed from original scripts and reviews. While not a completely lost film, its incomplete status makes screenings rare and valuable for cinema historians.