Waxworks

"Where Dreams and Nightmares Take Form in Wax"

Plot

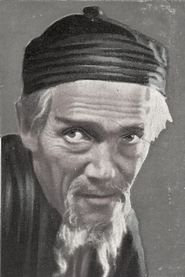

A young poet seeking employment is hired by the owner of a wax museum located within a traveling circus to write imaginative backstories for three of his most popular wax figures: the Caliph Harun al-Rashid, the Russian Tsar Ivan the Terrible, and the mysterious Jack the Ripper. As the poet works on his stories, he and the wax museum owner's daughter, Eva, find themselves increasingly immersed in these fantastic tales, imagining themselves as characters within each narrative. The film unfolds as an anthology, with each story coming to life through vivid Expressionist visuals and dreamlike sequences. The boundaries between reality and fantasy blur as the creative process transforms into a shared romantic journey for the young couple. The wax figures themselves seem to come alive, their stories becoming increasingly intertwined with the lives of their creators.

About the Production

This was one of the final major German Expressionist films before the movement's decline in the mid-1920s. The film's innovative use of moving cameras and fluid tracking shots represented a departure from the more static compositions typical of earlier Expressionist works. The wax museum sequences were particularly challenging to film, requiring elaborate lighting setups to create the eerie, lifelike quality of the figures. The production faced significant financial difficulties during filming, nearly leading to its cancellation before UFA stepped in to provide additional funding.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the height of the Weimar Republic's cultural golden age, a period of extraordinary artistic creativity in Germany despite economic and political instability. German Expressionism, which had dominated cinema since 'The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari' (1920), was beginning to evolve toward more realistic styles, and 'Waxworks' represents a transitional work incorporating both Expressionist visual elements and more naturalistic acting. The year 1924 was particularly significant in German cinema, marking the establishment of UFA as a major international studio and the beginning of German films' influence on Hollywood. The film's themes of authoritarian figures (Harun al-Rashid, Ivan the Terrible) and urban terror (Jack the Ripper) reflected contemporary anxieties about political instability and the dark side of modernization. The wax museum setting itself was a popular cultural phenomenon of the era, representing the public's fascination with both historical spectacle and macabre entertainment.

Why This Film Matters

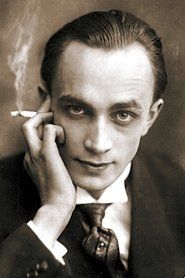

'Waxworks' holds a crucial place in cinema history as one of the most sophisticated examples of German Expressionist filmmaking and as a pioneering work in the horror anthology genre. Its influence can be traced through countless later films, from Universal's horror classics of the 1930s to modern anthology horror films. The film's innovative visual techniques, particularly its fluid camera movements and imaginative set designs, helped establish a visual language that would be adopted by filmmakers worldwide. Conrad Veidt's portrayal of Ivan the Terrible created a template for cinematic depictions of historical tyrants that would be referenced for decades. The film's exploration of the relationship between creator and creation, reality and illusion, anticipated later surrealist and psychological horror films. Its preservation and restoration in the late 20th century helped spark renewed interest in German Expressionist cinema among film scholars and enthusiasts.

Making Of

The production of 'Waxworks' was marked by significant creative tensions between its two credited directors, Paul Leni and Leo Birinski. Leni, who had a background in visual arts and set design, emphasized the film's Expressionist visual style, while Birinski focused more on the narrative structure and psychological elements. The casting process was particularly challenging, as Emil Jannings was initially reluctant to play the relatively small role of the wax museum owner, preferring more substantial dramatic parts. He was eventually persuaded by the opportunity to work with the innovative visual concepts Leni proposed. The elaborate wax museum set took weeks to construct, with special attention paid to lighting effects that would make the wax figures appear to move and change expression. Conrad Veidt underwent extensive makeup transformations for his role as Ivan the Terrible, spending up to four hours each day in the makeup chair. The film's most technically challenging sequence was the dreamlike transition between stories, which required innovative optical printing techniques that were cutting-edge for 1924.

Visual Style

The cinematography, primarily credited to Helmar Lerski, represents some of the most innovative work of the silent era. Lerski employed groundbreaking techniques including sweeping tracking shots that moved through the wax museum exhibits, creating a sense of fluid movement that was revolutionary for 1924. The lighting design was particularly sophisticated, using multiple light sources to create the illusion that the wax figures were actually moving and changing expression. Each of the three story segments had its own distinct visual style: the Harun al-Rashid sequence used warm, exotic lighting and elaborate set designs; the Ivan the Terrible segment employed stark, angular lighting and distorted perspectives to emphasize the tyrant's madness; and the Jack the Ripper sequence used deep shadows and limited lighting to create maximum suspense. The film also made innovative use of superimposition and double exposure techniques, particularly in the dream sequences that connect the three stories.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations that would influence cinema for decades. The most significant was its use of what Leni called 'the moving camera' - extensive tracking shots that glided through sets, creating a sense of continuous movement that was rare in 1924. The film also employed sophisticated optical printing techniques for its dream sequences and transitions between stories. The special effects used to bring the wax figures to life were particularly advanced for their time, using a combination of lighting tricks, multiple exposures, and carefully timed movements by actors in wax-like makeup. The set design by Robert Neppach and Erich Czerwonski featured movable elements that could be adjusted between takes to create the illusion of transformation. The film's makeup effects, particularly Conrad Veidt's transformation into Ivan the Terrible, set new standards for cinematic makeup artistry.

Music

As a silent film, 'Waxworks' would have been accompanied by live musical performances in theaters during its original release. The original German score was composed by Giuseppe Becce, one of the most prolific film composers of the silent era, who created specific musical themes for each of the three story segments. The Harun al-Rashid music incorporated Middle Eastern-inspired motifs, the Ivan the Terrible segment used dramatic, dissonant passages to emphasize the tyrant's madness, and the Jack the Ripper sequence employed suspenseful, atonal compositions. Different theaters would have adapted these scores based on their available musicians, ranging from full orchestras in prestigious cinemas to single pianists in smaller venues. Modern restorations of the film have featured newly composed scores by contemporary musicians, including versions by the Alloy Orchestra and others who attempt to recreate the spirit of the original while using modern musical sensibilities.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitle) 'In the realm of dreams, reality and fantasy dance as one'

(Intertitle) 'Every figure has a story waiting to be told'

(Intertitle) 'The wax remembers what history forgets'

(Intertitle) 'In the poet's mind, even death comes alive'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence tracking through the wax museum with its eerie, lifelike figures

- Conrad Veidt's manic performance as Ivan the Terrible during the feast scene

- The dreamlike transition between stories as the poet and Eva float through various landscapes

- The Jack the Ripper pursuit through foggy London streets with innovative use of shadows and lighting

- The final scene where the wax figures seem to come alive as the poet completes his stories

Did You Know?

- Director Paul Leni used innovative camera techniques including sweeping tracking shots that were revolutionary for the time, particularly in the Harun al-Rashid sequence

- Emil Jannings, who played the wax museum owner, would later become the first recipient of the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1929

- Conrad Veidt's portrayal of Ivan the Terrible was so intense that it reportedly frightened some cast members during filming

- The original screenplay was written by Henrik Galeen, who also wrote 'The Golem' (1920) and 'Nosferatu' (1922)

- The film's English title 'Waxworks' was actually given during its American release in 1925, while the German title was 'Das Wachsfigurenkabinett'

- William Dieterle, who later became a prominent Hollywood director, appears in a small role as one of the poets competing for the job

- The Jack the Ripper sequence was considered so terrifying that some theaters cut it entirely from their showings

- The film was one of the first to use the anthology format, influencing later horror compilation films

- The wax figures were created by prominent Berlin sculptor Hermann Haller, who was renowned for his realistic sculptures

- The film's original negative was believed lost for decades until a complete print was discovered in the Soviet Union archives in the 1970s

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release, German critics praised the film's visual inventiveness and technical achievements, with particular acclaim for Paul Leni's direction and the performances of Emil Jannings and Conrad Veidt. The film's anthology structure was noted as innovative, though some critics found the transitions between stories somewhat abrupt. International critics, especially in France and the United States, were impressed by the film's artistic ambitions and visual sophistication, though some found the horror elements too intense for mainstream audiences. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a masterpiece of Expressionist cinema, with many considering it superior to Leni's later Hollywood work. The film is now recognized for its influence on the horror genre and its role in transitioning German cinema from Expressionism to the more realistic 'New Objectivity' style that would dominate the late 1920s.

What Audiences Thought

Contemporary audience reactions were mixed but generally positive, with many viewers particularly impressed by the film's visual spectacle and the vivid storytelling of the three segments. The Harun al-Rashid sequence was especially popular with audiences, who enjoyed its exotic setting and romantic elements. However, the Jack the Ripper segment proved too intense for some viewers, leading to complaints and even walkouts in several theaters. Despite these challenges, the film performed reasonably well at the German box office, particularly in urban centers where audiences were more accustomed to avant-garde cinema. The film's international release was more limited, but it found appreciative audiences in France and Britain where German Expressionist films had developed a cult following. Modern audiences rediscovered the film through various restorations and revivals, with many contemporary viewers expressing surprise at the sophistication of its visual effects and storytelling techniques.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were given to the film during its initial release, as formal award ceremonies were not yet established in Germany

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- The Golem (1920)

- Nosferatu (1922)

- German Expressionist painting

- Gothic literature

- Edgar Allan Poe's tales

- The Thousand and One Nights

This Film Influenced

- Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932)

- The Black Cat (1934)

- Dead of Night (1945)

- The Fall of the House of Usher (1960)

- Creepshow (1982)

- Tales from the Darkside (1983)

- Pulp Fiction (1994)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered partially lost for decades until a complete 35mm print was discovered in the Soviet Union archives in the 1970s. This print had been seized by Soviet authorities after World War II and stored in the Gosfilmofond archive. The film underwent a major restoration by the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation in the 1990s, which involved cleaning the surviving elements and reconstructing missing scenes from various sources. The restored version premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1998. Several versions of varying quality exist, including tinted versions that replicate the original color effects used in some German releases. The film is now preserved in several major archives including the Museum of Modern Art, the British Film Institute, and the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv.