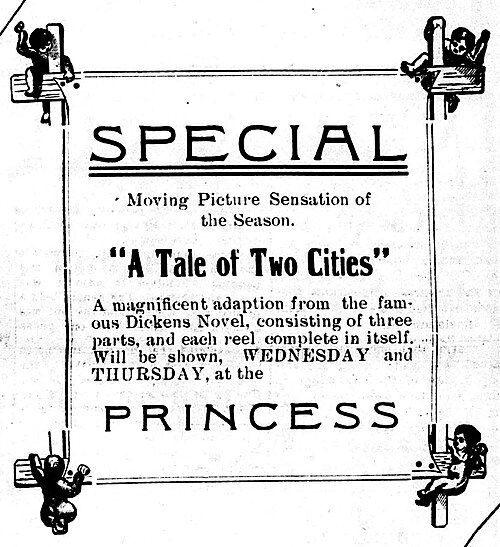

A Tale of Two Cities

Plot

This silent adaptation of Charles Dickens' classic novel follows the intertwined destinies of Charles Darnay, a French aristocrat who renounces his heritage to live in England, and Sydney Carton, a cynical English lawyer who secretly loves Darnay's wife Lucie. Set against the backdrop of the French Revolution and its Reign of Terror, the film depicts the stark contrasts between London and Paris societies. As revolutionary fervor consumes France, Darnay is imprisoned and sentenced to death, leading to Carton's ultimate sacrifice and redemption. The condensed narrative captures the novel's themes of resurrection, sacrifice, and the transformative power of love amid historical upheaval.

About the Production

This was one of the earliest cinematic adaptations of Dickens' work, created during a period when film studios were beginning to recognize the commercial potential of literary adaptations. The production faced the challenge of condensing Dickens' complex 45-chapter narrative into a format suitable for early cinema's time constraints. As was typical for Vitagraph productions of this period, the film was likely shot quickly on existing studio sets with minimal location work.

Historical Background

This film was produced during a transformative period in cinema history, when the medium was transitioning from novelty to legitimate art form. In 1911, the film industry was still establishing its conventions, with most productions being one-reel shorts of 10-15 minutes. The United States was rapidly becoming the world's dominant film producer, with companies like Vitagraph leading the way. The film's release coincided with growing international tensions that would eventually lead to World War I, though the French Revolution setting allowed for historical distance from contemporary political concerns. This period also saw the rise of the star system, with actors like Maurice Costello and Florence Turner developing fan followings that drove box office success.

Why This Film Matters

As one of the earliest film adaptations of a major literary work, this film represents an important milestone in the relationship between literature and cinema. It demonstrated the potential of film to bring classic stories to mass audiences who might never have read the original novels. The film also exemplifies the early 20th century American fascination with European history and culture, particularly dramatic periods like the French Revolution. Its production by Vitagraph, one of the pioneering American studios, reflects the growing sophistication of the U.S. film industry and its ambition to tackle complex literary subjects despite the technical limitations of the era.

Making Of

The production was typical of Vitagraph's approach during this period, utilizing their roster of contract players who were already familiar to audiences. Director William Humphrey was both an actor and director for Vitagraph, bringing his theatrical experience to the adaptation process. The film would have been shot on the company's Brooklyn studio lot, with painted backdrops and minimal sets representing both London and Paris. As with most films of this era, there was no recorded dialogue, so actors relied on exaggerated gestures and facial expressions to convey emotion. The intertitles would have been minimal due to the film's short length, relying instead on the audience's familiarity with the source material.

Visual Style

The cinematography would have been typical of Vitagraph productions in 1911, utilizing stationary camera positions with basic lighting setups. The film would have been shot on 35mm black and white film stock, with the cinematographer employing medium shots and close-ups to capture the actors' expressions. As was standard for the period, the visual style would have been theatrical in nature, with compositions influenced by stage presentations. The lack of location shooting meant that historical settings were created using studio sets and painted backdrops, requiring creative solutions to suggest the dual locations of London and Paris.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical terms, the film represented the growing sophistication of narrative cinema in 1911. The adaptation of such a complex literary work demonstrated the expanding capabilities of film storytelling within the constraints of the single-reel format. The film would have utilized Vitagraph's standard technical equipment and practices of the period, including their proprietary film processing methods. The production likely employed some of the early editing techniques being developed at the time, including cross-cutting between parallel storylines to maintain narrative coherence despite the extreme condensation of the source material.

Music

As a silent film, it would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The exact musical selections would have varied by venue, but typical accompaniment might include popular classical pieces, patriotic songs, and mood-appropriate selections from theater orchestras. Larger theaters might have employed small orchestras, while smaller venues used piano accompaniment. The music would have been chosen to enhance the dramatic moments and help convey the emotional tone of scenes, particularly during the revolutionary sequences and the film's climactic scenes.

Famous Quotes

It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times

Recalled to life

Memorable Scenes

- The final guillotine scene where Sydney Carton sacrifices himself for Charles Darnay, which would have been the emotional climax of the condensed adaptation, featuring dramatic gestures and expressions typical of silent era acting to convey the momentous sacrifice without dialogue

Did You Know?

- This film is now considered lost, as no known copies survive in any film archive or private collection

- It was one of at least three different film adaptations of 'A Tale of Two Cities' released in 1911, demonstrating the novel's enduring popularity

- John Bunny, who played a role in this film, was one of the first true film comedians and had his own production company at Vitagraph

- The film was released during the golden age of silent film adaptations of literary classics, when studios raced to bring famous novels to the screen

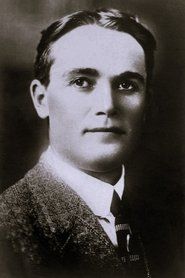

- Maurice Costello, one of the stars, was known as 'the first matinee idol of American cinema' and was one of the highest-paid actors of his time

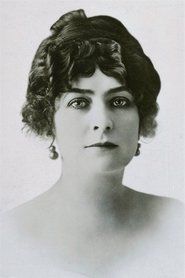

- Florence Turner was often called 'the Vitagraph Girl' and was one of America's first movie stars with a devoted fan following

- The film's release came just 16 years after the birth of cinema, making it an extremely early example of literary adaptation

- Vitagraph Studios was one of the most prolific production companies of the early silent era, producing hundreds of short films annually

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews in trade publications like The Moving Picture World generally praised the film for its ambitious attempt to adapt such a complex novel. Critics noted the quality of the performances, particularly Maurice Costello's portrayal of the dual protagonists. However, some reviewers expressed concern about the extreme condensation required to fit the story into a single reel. Modern critics cannot evaluate the film directly due to its lost status, but film historians recognize it as an important example of early literary adaptation and the development of narrative cinema techniques.

What Audiences Thought

The film was reportedly well-received by audiences of 1911, who were familiar with the source material and appreciated seeing the famous characters brought to life on screen. The star power of Maurice Costello and Florence Turner likely contributed to its commercial success. Audiences of this era were still marveling at the magic of moving pictures, and literary adaptations provided a familiar framework for understanding this new medium. The film's brevity made it suitable for the typical theater program of the time, which usually featured multiple short films.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Charles Dickens' novel 'A Tale of Two Cities' (1859)

- Stage adaptations of Dickens' work

- Earlier literary film adaptations by Vitagraph

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent film adaptations of 'A Tale of Two Cities' (1917, 1922, 1935, 1958, 1980, 2008)

- Other Vitagraph literary adaptations

- Early historical dramas in cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Lost film - no known copies survive in any film archive or private collection. Like approximately 90% of American films produced before 1920, this film has been lost due to the decomposition of nitrate film stock and inadequate preservation practices in the early film industry.