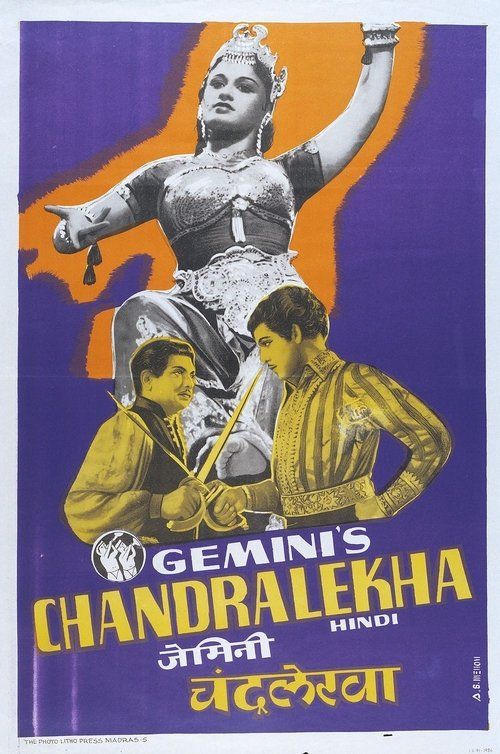

Chandralekha

"The Greatest Indian Spectacle Ever Filmed!"

Plot

Chandralekha tells the epic tale of two brothers, Veer Singh and Shashank, heirs to a royal kingdom who both fall deeply in love with the beautiful and independent village dancer Chandralekha. When their father dies, the evil Shashank usurps the throne and imprisons his virtuous brother Veer, then kidnaps Chandralekha and forces her to agree to marry him. On the day of the wedding, Chandralekha cleverly requests a special drum dance performance, which serves as a secret signal to Veer's loyal followers who have been hiding in the countryside. The drums contain weapons, and during the performance, Veer's army emerges, leading to an spectacular battle between the brothers' forces. In the end, good triumphs as Veer defeats Shashank and wins Chandralekha's hand, restoring justice to the kingdom.

About the Production

The film took five years to complete (1943-1948) due to various production challenges including World War II restrictions on film stock. The famous drum dance sequence alone took six months to choreograph and film. Over 400 dancers and extras were employed for the spectacular finale battle sequence. The film's elaborate sets included a full-scale replica of a royal palace and massive outdoor locations for the battle scenes.

Historical Background

Chandralekha was produced and released during a pivotal moment in Indian history - just months after India gained independence from British rule in August 1947. The film's themes of justice, freedom, and the triumph of good over evil resonated deeply with a nation experiencing its first taste of self-governance. The late 1940s also saw the Indian film industry transitioning from the colonial era to an independent identity, with filmmakers exploring more ambitious projects. The film's massive budget and scale reflected the newfound optimism and ambition of post-independence India. Additionally, the period saw growing tensions between India and Pakistan, and the film's message of unity and justice served as a subtle commentary on the need for national cohesion during challenging times.

Why This Film Matters

Chandralekha revolutionized Indian cinema by establishing the template for the big-budget spectacle film. Its success proved that Indian audiences would embrace films with grand production values, elaborate dance sequences, and spectacular action scenes. The film's nationwide release strategy in multiple languages created a new model for film distribution in India's multilingual market. The drum dance sequence became iconic and has been referenced and parodied in numerous Indian films over the decades. The film also elevated the status of the South Indian film industry, proving that regional cinema could compete with Bollywood in terms of quality and commercial success. Chandralekha's influence can be seen in the grandeur of modern Indian epics and historical films, and it remains a reference point for filmmakers attempting large-scale productions.

Making Of

The making of Chandralekha was as epic as the film itself. Production began in 1943 but faced numerous setbacks, including the loss of the initial footage in a studio fire. Director S. S. Vasan, known as a perfectionist, insisted on reshooting everything with even grander vision. The casting process was rigorous - T. R. Rajakumari was chosen from over 200 actresses for the title role after a series of screen tests. The film's most elaborate sequence, the drum dance, required months of preparation. The drums were specially designed with hollow interiors to conceal weapons, a detail that required close coordination between the prop department and choreographers. The massive battle sequence was filmed over 45 days with hundreds of extras, many of whom were actual martial artists recruited from local gymnasiums. The film's post-production took over a year due to the complex editing and special effects required for the action sequences.

Visual Style

The cinematography by K. Ramnoth was groundbreaking for Indian cinema. He employed innovative camera techniques including dramatic low angles for the palace sequences, sweeping crane shots for the battle scenes, and close-ups that emphasized the emotional intensity of the performances. The drum dance sequence featured complex tracking shots that followed the dancers' movements in perfect synchronization. Ramnoth used special lighting techniques to create dramatic shadows and highlights, particularly in the palace interiors and night scenes. The film also made extensive use of matte paintings and miniature effects for establishing shots of the kingdom, techniques that were rarely used in Indian cinema at the time. The battle sequences utilized multiple cameras to capture the scale of the action, a technique that would become standard in later Indian action films.

Innovations

Chandralekha pioneered several technical innovations in Indian cinema. The film was one of the first to use synchronous sound recording for the elaborate dance sequences. The special effects team created innovative techniques for the battle scenes, including wire work for stunt sequences and pyrotechnics that were far more sophisticated than anything previously seen in Indian films. The production design team built some of the largest sets ever constructed in Indian cinema up to that time, including a full-scale replica of a royal palace that covered over two acres. The film's editing techniques, particularly in the action sequences, introduced a new level of dynamism to Indian film editing. The drum dance sequence required the development of special sound recording equipment to capture the complex percussion arrangements accurately.

Music

The music for Chandralekha was composed by the legendary duo S. Rajeswara Rao and M. D. Parthasarathy, with lyrics by Papanasam Sivan and Kothamangalam Subbu. The soundtrack became immensely popular and is still remembered today. The film featured 12 songs, each carefully integrated into the narrative. The most famous was the drum dance sequence music, which combined traditional Indian percussion with orchestral arrangements. The songs showcased a blend of classical Carnatic music with more contemporary orchestration, reflecting the film's approach of combining traditional Indian elements with modern cinematic techniques. The soundtrack was released in both Tamil and Hindi versions, with different lyricists but maintaining the same musical compositions. The film's music played a crucial role in its success, with records selling in record numbers across India.

Famous Quotes

Chandralekha: 'The drums that dance today will sing the song of freedom tomorrow!'

Veer Singh: 'Justice may be delayed, but it can never be defeated.'

Shashank: 'Power is not given, it is taken!'

Chandralekha: 'A woman's heart is not a prize to be won, but a gift to be earned.'

Memorable Scenes

- The legendary drum dance sequence where 200 dancers perform with drums containing hidden weapons, culminating in a dramatic revelation and the beginning of the rebellion

- The spectacular battle sequence between the brothers' armies, featuring hundreds of extras, real weapons, and groundbreaking stunt choreography

- Chandralekha's defiant speech before her forced wedding, where she declares her loyalty to justice over tyranny

- The opening sequence establishing the royal kingdom with elaborate palace sets and grand processions

Did You Know?

- Chandralekha was the first Indian film to have a nationwide release using multiple language versions (Tamil and Hindi simultaneously)

- The film's budget of ₹30 lakh was equivalent to the cost of building 10 luxury homes in Madras at the time

- Director S. S. Vasan mortgaged his entire studio to finance the film's production

- The famous drum dance sequence featured 200 dancers and was choreographed by renowned dance master Vazhuvoor Ramiah Pillai

- The film's success established Gemini Studios as one of India's premier film production houses

- A special train called the 'Chandralekha Express' was used to transport the film's prints across India for its release

- The battle sequence in the climax used real swords and weapons, though blunted for safety

- The film was India's official entry to the Venice Film Festival in 1948

- S. S. Vasan reportedly spent more on the film's publicity than most films' entire production budgets

- The film's sets were so elaborate that they remained standing for years as tourist attractions at Gemini Studios

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics hailed Chandralekha as a masterpiece of Indian cinema. The Times of India called it 'a landmark in Indian filmmaking that sets new standards for production values and artistic achievement.' International critics at the Venice Film Festival praised its visual spectacle and technical excellence. Modern critics continue to regard it as a classic, with the British Film Institute describing it as 'one of the most important films in Indian cinema history.' The film is particularly praised for its innovative cinematography, especially in the drum dance and battle sequences. However, some contemporary critics noted that the plot followed conventional melodramatic patterns, though they acknowledged that the execution was extraordinary.

What Audiences Thought

Chandralekha was a phenomenal success with audiences across India. The film broke box office records in every major city and ran for over 200 days in many theaters, achieving 'silver jubilee' status. Audiences were particularly captivated by the drum dance sequence, which became a cultural phenomenon. The film's dialogue and songs became popular catchphrases, and Chandralekha's character became an iconic representation of the strong, independent Indian woman. The film's success was unprecedented for a South Indian production in North Indian markets, proving that regional cinema could have nationwide appeal. Even decades after its release, the film continues to be screened at film festivals and retrospectives, drawing enthusiastic responses from both older audiences who remember its original release and younger viewers discovering it for the first time.

Awards & Recognition

- Best Film Award at the 1st Filmfare Awards (1954) - Special Award for Cinematic Excellence

- Certificate of Merit for Best Feature Film in Tamil at the National Film Awards (India)

- Best Art Direction Award at the International Film Festival of India

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Hollywood historical epics such as 'The Adventures of Robin Hood' (1938)

- Indian classical dance traditions

- Traditional Indian folk theater forms

- Mythological Indian stories from the Mahabharata and Ramayana

This Film Influenced

- Mughal-e-Azam (1960)

- Sholay (1975)

- Lagaan (2001)

- Baahubali series (2015-2017)

- Padmaavat (2018)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been partially preserved by the National Film Archive of India (NFAI), though some elements have deteriorated over time. In 2010, a restoration project was undertaken by the Film Heritage Foundation in collaboration with Martin Scorsese's Film Foundation. The restored version premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2011. However, some original elements, particularly the original camera negatives, have been lost due to improper storage in the tropical climate of South India. The surviving prints are occasionally screened at film festivals and special retrospectives, though the quality varies depending on the source material.