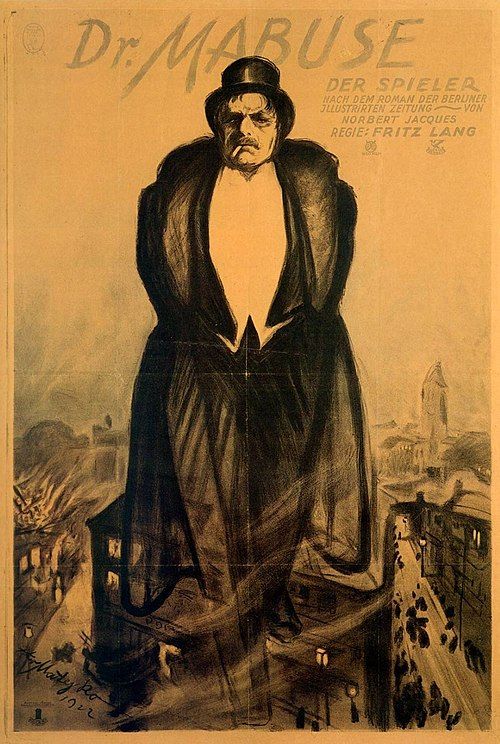

Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler

"A Master of Disguise and Hypnotic Power Rules the Criminal Underworld"

Plot

Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler follows the exploits of Dr. Mabuse, a criminal mastermind and master of disguise who uses hypnotic powers and psychological manipulation to control a vast criminal empire in 1920s Berlin. Operating from his secret headquarters, Mabuse orchestrates elaborate schemes including stock market manipulation, counterfeiting operations, and targeted thefts, all while maintaining multiple identities. When Police Commissioner von Wenk begins investigating a series of mysterious crimes that seem psychologically orchestrated, he finds himself pitted against Mabuse's sophisticated criminal network. The film explores Mabuse's psychological warfare against his victims and the authorities, particularly his manipulation of wealthy targets like Edgar Hull through rigged card games and hypnotic suggestion. As the investigation intensifies, Mabuse's empire begins to unravel under pressure from both law enforcement and internal betrayals, leading to a climactic confrontation between the criminal mastermind and the determined police commissioner.

About the Production

The film was originally released in two parts due to its considerable length. Part 1 was titled 'Der große Spieler: Ein Bild der Zeit' (The Great Gambler: A Picture of the Time) and Part 2 was 'Inferno: Ein Spiel von Menschen unserer Zeit' (Inferno: A Play of People of Our Time). The production employed over 100 actors and featured elaborate sets designed by Hermann Warm, Robert Neppach, and Erich Kettelhut. The film's shooting schedule extended over several months in 1921-1922, requiring complex logistics for the numerous location and studio scenes depicting 1920s Berlin nightlife.

Historical Background

Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler emerged during a turbulent period in German history, the early years of the Weimar Republic. The film was produced in 1921-1922, during the height of the hyperinflation crisis that would devastate the German economy in 1923. This economic chaos, combined with the social upheaval following World War I, created fertile ground for stories about criminal masterminds and social decay. The film's depiction of a shadowy criminal empire manipulating society from behind the scenes resonated with contemporary fears about political extremism and organized crime. Berlin during this period was known for its decadent nightlife, artistic experimentation, and moral ambiguity, all of which are reflected in the film's atmosphere. The character of Dr. Mabuse can be seen as an embodiment of the anxieties about modernity, psychology, and the loss of traditional values that characterized German intellectual life in the early 1920s. The film's release preceded the golden age of German Expressionist cinema but already showed the movement's influence in its visual style and psychological themes.

Why This Film Matters

Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler holds immense cultural significance as a foundational text in the development of the cinematic supervillain archetype. The character of Dr. Mabuse established the template for the criminal mastermind who uses psychological manipulation rather than brute force, influencing countless later characters from James Bond villains to Batman's adversaries. The film's exploration of mass psychology and manipulation proved prescient, anticipating the rise of totalitarian movements in Europe. Its visual style, combining Expressionist lighting with realistic location shooting, helped bridge the gap between German Expressionism and the more naturalistic styles that would follow. The film's structure as a two-part epic influenced the development of the crime thriller genre, demonstrating how complex criminal conspiracies could be portrayed on screen. In Germany, the film became part of the cultural conversation about modernity and its discontents, while internationally, it helped establish Fritz Lang's reputation as one of cinema's great auteurs. The Mabuse character himself became a recurring figure in German popular culture, appearing in two subsequent Lang films and numerous other media adaptations.

Making Of

The production of Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler was a massive undertaking for the German film industry of 1922. Fritz Lang and his wife Thea von Harbou co-wrote the screenplay, adapting Jacques's novel with significant additions to create a sprawling epic that captured the decadent atmosphere of Weimar Berlin. The casting of Rudolf Klein-Rogge as Mabuse proved pivotal, as his intense, theatrical performance established the template for cinematic supervillains. The film's production design was extraordinarily ambitious, featuring detailed recreations of Berlin's high society venues, underground gambling dens, and opulent interiors. Lang insisted on shooting many scenes on location in actual Berlin establishments to achieve authenticity, a practice that was relatively uncommon for large-scale productions of the era. The hypnotic sequences required innovative camera techniques and multiple exposures, pushing the technical boundaries of silent cinema. The production faced significant challenges due to post-war economic conditions in Germany, including shortages of film stock and resources, yet managed to create one of the most visually sophisticated films of its time.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler, primarily by Carl Hoffmann and Fritz Arno Wagner, represents a pivotal moment in German visual storytelling. The film masterfully blends Expressionist lighting techniques with location photography, creating a distinctive visual language that bridges stylized studio work and documentary-like realism. The camera work employs innovative techniques including tracking shots, unusual angles, and sophisticated use of shadows to create psychological tension. The hypnotic sequences feature groundbreaking special effects using multiple exposures and superimposition to visualize Mabuse's mental control over his victims. The cinematography of the casino and nightclub scenes uses dynamic camera movement and elaborate lighting to capture the decadent atmosphere of 1920s Berlin. The visual contrast between Mabuse's shadowy underworld and the opulent world of his victims is achieved through careful lighting design and composition. The film's visual style influenced countless later noir and thriller films, establishing visual conventions for depicting criminal psychology and urban decay that would become genre staples.

Innovations

Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler featured numerous technical innovations that pushed the boundaries of early 1920s filmmaking. The film's special effects, particularly in the hypnotic sequences, used sophisticated multiple exposure techniques to create visual representations of psychological manipulation. The production employed elaborate camera movements including tracking shots and crane work that were technically advanced for the period. The film's lighting design combined Expressionist techniques with realistic location lighting, creating a distinctive visual aesthetic that influenced subsequent film noir. The use of actual Berlin locations alongside studio sets represented an innovative approach to production design. The film's editing, particularly in the cross-cutting between parallel action sequences, demonstrated sophisticated narrative techniques that helped maintain tension across its considerable running time. The makeup and disguise effects used for Mabuse's various transformations were particularly advanced, allowing Rudolf Klein-Rogge to convincingly portray multiple characters. The film's sound design, while limited by the technology of the era, used visual and rhythmic techniques to create auditory illusions through synchronized action.

Music

As a silent film, Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler would have been accompanied by live musical performances during its original theatrical run. The specific scores used in 1922 are not documented, as was typical for the period, with theaters often using stock music or improvisation. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores, most notably a 2014 version by the German ensemble Alraune, which attempts to recreate the musical atmosphere of 1920s Berlin cabarets and classical concert halls. The original German release likely included popular songs of the era and classical pieces, particularly during the nightclub scenes at the Folies Bergères. Contemporary screenings often feature either improvised accompaniment or specially commissioned scores that blend jazz, classical, and experimental elements to match the film's psychological intensity. The absence of synchronized sound actually enhances the film's exploration of non-verbal communication and psychological manipulation, with Lang's visual storytelling doing the work that dialogue would later accomplish.

Famous Quotes

While the film is silent and contains no spoken dialogue, intertitles include key lines such as: 'I am the state!' - Dr. Mabuse's declaration of power

'The human will is the weakest thing in the world' - Mabuse's philosophy of manipulation

'In this game, I am the bank' - Mabuse at the card table

'Your mind is my playground' - During hypnotic sequences

'Fear is the most powerful weapon' - Mabuse's method of control

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Mabuse's criminal network operating across Berlin

- The hypnotic card game where Mabuse psychologically destroys Edgar Hull

- The elaborate disguise sequence where Mabuse transforms into multiple characters

- The police raid on the underground casino, featuring dynamic camera work and chaos

- The final confrontation between Mabuse and Commissioner von Wenk in Mabuse's headquarters

- The Folies Bergères sequence capturing the decadent nightlife of 1920s Berlin

- The stock market manipulation scene showing Mabuse's financial crimes

- The psychological torture sequences demonstrating Mabuse's methods of control

Did You Know?

- The film was based on the novel 'Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler' by Luxembourgish writer Norbert Jacques, who created the character specifically for this adaptation

- Rudolf Klein-Rogge, who played Dr. Mabuse, was married to director Fritz Lang at the time of filming (they divorced in 1923)

- The film was originally over 5 hours long but was cut down for theatrical release

- This was the first of three films Fritz Lang would make about the Dr. Mabuse character, spanning four decades

- The character of Dr. Mabuse was partly inspired by real-life criminal masterminds and the atmosphere of post-WWI Germany

- The film's depiction of stock market manipulation was particularly relevant during the hyperinflation crisis in Germany

- Many of the extras in the casino and nightclub scenes were actual Berlin underworld figures

- The film's elaborate special effects, including superimpositions for hypnotic sequences, were considered groundbreaking for 1922

- The original negative was heavily damaged during WWII but was later restored using various international prints

- The character's name 'Mabuse' was derived from the painter Quentin Metsys, also known as Quentin Massys

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler was largely positive, with German critics praising its ambitious scope and sophisticated narrative structure. The film was recognized as a major achievement in German cinema, with particular appreciation for Rudolf Klein-Rogge's performance and Fritz Lang's direction. Critics noted the film's timely commentary on post-war German society and its innovative visual techniques. International critics were equally impressed when the film was exported, with reviews in France and Britain highlighting its psychological depth and technical accomplishments. Over time, critical appreciation has only grown, with modern film scholars considering it a masterpiece of silent cinema and a crucial work in understanding the development of the thriller genre. Contemporary critics often cite it as a precursor to film noir and note its influence on directors ranging from Alfred Hitchcock to Brian De Palma. The film is now studied for its sophisticated treatment of themes like mass psychology, the nature of evil, and the relationship between crime and modern capitalism.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception in 1922 Germany was generally enthusiastic, with the film proving popular despite its considerable length. The two-part release strategy allowed audiences to experience the story in manageable segments, and both parts performed well at the box office. Contemporary audience reports suggest that viewers were particularly impressed by the film's depiction of Berlin's criminal underworld and its realistic portrayal of the city's nightlife. The hypnotic sequences and special effects generated significant buzz, with word-of-mouth helping to drive attendance. The character of Dr. Mabuse proved particularly compelling to audiences, becoming something of a cultural phenomenon in Germany. The film's success led to increased interest in psychological thrillers and helped establish the crime genre as commercially viable in German cinema. Modern audiences, particularly those interested in film history and silent cinema, continue to be drawn to the film's sophisticated narrative and visual style, with restored versions regularly screening at film festivals and cinematheques worldwide.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were documented for this film, as the German film award system was not yet established in 1922

Film Connections

Influenced By

- German Expressionist cinema

- The novels of Norbert Jacques

- The works of Edgar Allan Poe

- Contemporary German crime literature

- The social conditions of Weimar Germany

- Early psychological theories of Freud and Jung

- The tradition of the master criminal in literature

- Post-WWI German social commentary

This Film Influenced

- The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933)

- The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960)

- M (1931)

- The Third Man (1949)

- The Big Sleep (1946)

- Batman: The Animated Series (1992-1995)

- The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

- Inception (2010)

- The Dark Knight (2008)

- Casino Royale (2006)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved and restored multiple times. The original German negative suffered significant damage during World War II, but various international prints and elements survived. A major restoration was undertaken by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung in the early 2000s, combining elements from German, American, and French sources to create the most complete version available. The restored version runs approximately 237 minutes and includes tinted sequences that replicate the original color schemes. The film is now preserved in several archives worldwide, including the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv in Berlin and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Digital restorations have made the film accessible on Blu-ray and streaming platforms, ensuring its preservation for future generations.