Fighting Blood

Plot

Set in the aftermath of the American Civil War, 'Fighting Blood' follows a former Union soldier who relocates his family to the untamed Dakota Territory to start a new life. Tensions rise when the young son, portrayed by Robert Harron, quarrels with his father and defiantly leaves their homestead. While riding alone in the surrounding hills, the son witnesses a band of Native Americans attacking a neighboring family's settlement. Realizing the imminent danger to his own family, he races back to warn them, pursued relentlessly by the attacking warriors in a thrilling chase sequence that tests his courage and loyalty.

About the Production

This film was produced during D.W. Griffith's prolific period at Biograph, where he directed hundreds of short films. The production utilized the natural landscapes of New Jersey and California to stand in for the Dakota Territory, a common practice in early Westerns. The film was shot on 35mm black and white film stock typical of the era, with Griffith already beginning to experiment with more sophisticated camera techniques and narrative structures that would later define his style.

Historical Background

1911 was a pivotal year in American cinema, occurring during the transition from the novelty period of film to the emergence of narrative storytelling as the dominant form. The film industry was consolidating around the Motion Picture Patents Company (the 'Edison Trust'), though independent producers were already challenging this monopoly. D.W. Griffith was at Biograph during this period, rapidly advancing the art of cinematic storytelling through techniques like cross-cutting, varied camera angles, and sophisticated narrative structures. The Western genre was particularly popular during this era, reflecting America's ongoing fascination with frontier mythology and the recent closing of the frontier. The depiction of Native Americans in films like 'Fighting Blood' reflected contemporary attitudes and stereotypes, presenting them as antagonists in the settlement narrative. This was also the year before the industry's major migration from the East Coast to Hollywood, making films like this part of the final wave of significant productions centered around the New York area.

Why This Film Matters

'Fighting Blood' represents an important milestone in the development of the Western genre and American narrative cinema. As one of D.W. Griffith's early attempts at sophisticated storytelling within the constraints of a one-reel format, it demonstrates the director's growing mastery of cinematic techniques that would later revolutionize filmmaking. The film contributed to the establishment of Western tropes that would dominate American cinema for decades, including the noble pioneer family, the threatening Native American 'other,' and the redemption of the rebellious son through heroic action. Its survival provides modern viewers with a window into early 20th-century American values and racial attitudes, particularly regarding the settlement of the American West. The film also showcases Griffith's early experiments with suspense and action sequences, techniques that would influence countless future directors and help establish the visual language of cinema.

Making Of

The production of 'Fighting Blood' took place during a transformative period in American cinema when D.W. Griffith was rapidly developing the language of film. Working under the constraints of the Biograph Company's one-reel format (approximately 17 minutes), Griffith had to tell a complete story with character development, conflict, and resolution in a remarkably short time. The film was shot on location in Fort Lee, New Jersey, which was then the center of American film production before the industry's migration to Hollywood. Griffith was already beginning to employ techniques that would become cinematic staples, including cross-cutting between parallel actions during the chase sequence and the use of close-ups to emphasize emotional moments. The cast was drawn from Griffith's regular troupe of Biograph actors, with whom he had developed a shorthand communication style that allowed for efficient filming despite the primitive working conditions of early cinema sets.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'Fighting Blood' was handled by Billy Bitzer or Arthur Marvin, Griffith's regular cameramen at Biograph. The film exhibits the relatively static camera positions typical of 1911, but Griffith was already beginning to vary his shot sizes and angles to enhance storytelling effectiveness. The outdoor location shooting allowed for natural lighting, which gave the images a greater sense of realism compared to studio-bound productions. The chase sequence would have employed multiple camera setups to capture the pursuit from different perspectives, demonstrating the emerging technique of cross-cutting to build suspense. The composition of shots follows the theatrical traditions of the era, with actors typically positioned center-frame, but Griffith was already experimenting with more dynamic framing to emphasize emotional moments and action sequences.

Innovations

While 'Fighting Blood' may not appear technically sophisticated by modern standards, it represented several important achievements for its time. The film's effective use of cross-cutting during the chase sequence was relatively advanced for 1911, demonstrating Griffith's growing mastery of parallel action editing. The location shooting in natural settings, rather than relying entirely on painted backdrops, provided a greater sense of realism that was still uncommon in many productions of the era. The film's successful compression of a complete narrative arc into a single reel showed Griffith's developing skill in economical storytelling. The coordination of the action sequences, particularly the chase scenes with horseback riding, required considerable logistical planning in an era before sophisticated stunt coordination. These technical elements, while individually modest, collectively contributed to the film's effectiveness and pointed toward the more sophisticated techniques Griffith would develop in his later work.

Music

As a silent film, 'Fighting Blood' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original exhibition. The specific musical score is not documented, but typical accompaniment for a Western drama of this period would have included popular songs of the era, classical excerpts, and improvisation by the theater's pianist or organist. The music would have been synchronized to the on-screen action, with faster tempos during the chase sequence and more somber melodies for emotional moments. Some theaters might have used compiled 'cue sheets' that suggested appropriate musical pieces for different scenes. The lack of a fixed soundtrack meant that each exhibition of the film could have a unique musical interpretation depending on the skill and repertoire of the individual musician.

Did You Know?

- This was one of approximately 300 short films D.W. Griffith directed for the Biograph Company between 1908 and 1913.

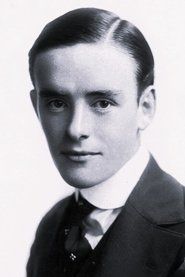

- Robert Harron, who plays the son, would become one of Griffith's most frequently used actors, appearing in many of his major films including 'The Birth of a Nation' and 'Intolerance'.

- The film was released when Westerns were becoming increasingly popular with American audiences, reflecting the nation's fascination with frontier mythology.

- Like many films of this era, 'Fighting Blood' was likely shot in just a few days due to the rapid production schedule at Biograph.

- The Native American characters in the film were portrayed by white actors in makeup, a common and now controversial practice of the time.

- The film's title refers to the idea of inherited or innate fighting spirit, a theme Griffith explored in several of his early works.

- This film survives today in the archives of the Museum of Modern Art and the Library of Congress.

- The chase sequence was considered particularly exciting for 1911 audiences and demonstrated Griffith's growing mastery of action filmmaking.

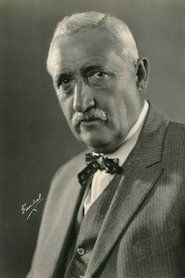

- George Nichols, who plays the father, was the father of famed director Hal Roach and appeared in over 200 films between 1908 and 1930.

- Kate Bruce, who portrays the mother, was another regular in Griffith's Biograph films, appearing in more than 150 of his shorts.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception of 'Fighting Blood' is difficult to document thoroughly due to the limited film criticism infrastructure of 1911. However, reviews in trade publications like The Moving Picture World generally praised Griffith's Biograph productions for their technical quality and storytelling sophistication. Modern film historians and critics view the film as an important example of Griffith's early development as a director, noting his emerging mastery of cross-cutting during the chase sequence and his ability to create emotional resonance within the severe time constraints of a one-reel film. While not as celebrated as Griffith's later feature-length epics, 'Fighting Blood' is recognized by scholars as a significant work in the director's filmography and in the broader development of American narrative cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception of 'Fighting Blood' in 1911 was generally positive, as evidenced by the continued demand for Griffith's Biograph films during this period. The film's Western theme and action elements appealed strongly to contemporary moviegoers, particularly working-class audiences who frequented nickelodeons. The chase sequence, in particular, would have provided the kind of thrilling spectacle that early cinema audiences craved. The father-son conflict and ultimate reconciliation offered emotional depth that elevated the film above simpler action pictures of the era. While specific box office records for individual Biograph shorts are not available, the company's continued production of similar films suggests that audiences responded well to this formula. Modern audiences viewing the film in archival contexts often appreciate it as a historical artifact that demonstrates both the limitations and achievements of early narrative cinema.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage melodramas of the late 19th century

- Contemporary dime novels about the West

- Earlier Biograph Western shorts

- Theatrical traditions of American frontier drama

- Popular literature about post-Civil War settlement

This Film Influenced

- Later Griffith Western shorts

- The development of chase sequences in silent cinema

- The father-son reconciliation trope in Western films

- Biograph's subsequent Western productions