In the Land of the Head Hunters

Plot

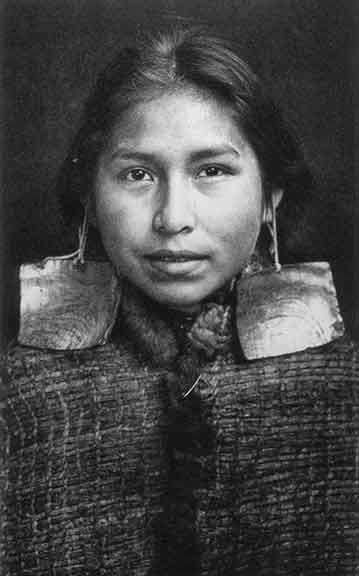

In the Land of the Head Hunters follows the story of Motana, the son of a Kwakwaka'wakw chief, who seeks to marry Naida, the beautiful daughter of a sorcerer. To prove his worthiness, Motana must undertake a dangerous quest to slay the feared sea monster, the Gonakadet. After successfully completing this task and marrying Naida, Motana's village is attacked by a rival tribe, leading to his capture and enslavement. Through his courage and the help of supernatural forces, Motana eventually escapes and returns to reclaim his bride and restore honor to his people. The film combines elements of romance, adventure, and traditional Kwakwaka'wakw mythology, showcasing ceremonial dances, totem pole carving, and other cultural practices.

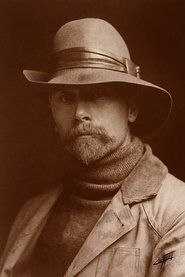

About the Production

Edward S. Curtis, primarily known as an ethnographic photographer, invested $75,000 of his own money into this project. He spent three years making the film, living among the Kwakwaka'wakw people and gaining their trust. The production faced numerous challenges including the remote filming location, technical difficulties with early film equipment, and the need to transport heavy equipment by canoe to coastal villages. Curtis encouraged the Kwakwaka'wakw actors to revive traditional ceremonies and practices that had been suppressed by Canadian authorities, including potlatch ceremonies that were illegal at the time.

Historical Background

In 1914, when this film was made, Native American and First Nations peoples were facing intense pressure to assimilate into mainstream North American society. In Canada, the potlatch ceremony—a central part of Kwakwaka'wakw culture—had been banned since 1885 as part of government efforts to suppress indigenous traditions. The film industry itself was still in its infancy, with feature films only recently becoming common. Ethnographic filmmaking was virtually nonexistent, and most representations of Native peoples in popular media were stereotypical and often played by white actors in makeup. Curtis's work represented a radical departure from these practices, though it still reflected the paternalistic attitudes of the time, viewing indigenous cultures as vanishing and needing preservation. The film emerged during a period of renewed interest in Native American cultures among some segments of white society, even as government policies continued to suppress indigenous practices.

Why This Film Matters

In the Land of the Head Hunters holds immense cultural significance as a rare visual record of Kwakwaka'wakw culture at a time when traditional practices were being actively suppressed. The film documents authentic ceremonial regalia, dances, and cultural practices that might otherwise have been lost. For the Kwakwaka'wakw people today, the film represents an invaluable connection to their ancestors and traditions. It also marks an important milestone in film history as the first feature with an entirely Native North American cast, challenging the Hollywood convention of white actors playing indigenous roles. The film's restoration and re-release has sparked renewed interest in Curtis's work and its complex legacy—both as a preservation effort and as an example of outsider interpretation of indigenous culture. Contemporary scholars and indigenous communities continue to debate Curtis's methods and motives, but the film's value as a cultural document remains undisputed.

Making Of

Edward S. Curtis approached filmmaking as an extension of his ethnographic work, aiming to preserve what he believed were the disappearing cultures of Native Americans. He spent considerable time living with the Kwakwaka'wakw people, documenting their daily lives and ceremonies. The production was a collaborative effort between Curtis and the Kwakwaka'wakw community, who provided authentic costumes, props, and cultural knowledge. Many of the ceremonial objects and regalia used in the film were actual sacred items that had been preserved by families despite government bans. The filming process itself was arduous, requiring the crew to transport equipment by canoe to remote coastal villages. Curtis encouraged the revival of traditional practices that had been suppressed, including potlatch ceremonies that were illegal under Canadian law at the time. The Kwakwaka'wakw participants saw the film as an opportunity to preserve their cultural heritage and share it with the world.

Visual Style

The cinematography of In the Land of the Head Hunters is remarkable for its time, featuring stunning location photography in the coastal wilderness of British Columbia. Curtis applied his photographic eye to the moving image, creating carefully composed shots that highlight both the natural beauty of the landscape and the intricate details of Kwakwaka'wakw ceremonial regalia. The film makes effective use of the coastal setting, with dramatic shots of war canoes against mountain backdrops and scenes filmed on the open water. Curtis employed innovative techniques for the period, including underwater photography for scenes involving the sea monster. The original film included color tinting for certain scenes, particularly those involving supernatural elements, adding visual interest to the otherwise black and white footage. The restored version reveals the sophistication of the cinematography, with shots that demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of visual storytelling.

Innovations

In the Land of the Head Hunters featured several technical innovations for its time. Curtis employed the latest camera equipment available in 1914, allowing for location filming in challenging coastal environments. The production utilized special effects techniques to create the sea monster sequence, including underwater photography and mechanical props. The film's use of authentic locations rather than studio sets was unusual for a feature of this period. The original 35mm nitrate film stock was fragile, making the survival of any footage remarkable. The 2013 digital restoration used state-of-the-art technology to repair damage, stabilize the image, and enhance the surviving footage while preserving the visual character of the original. This restoration represents a significant achievement in film preservation, demonstrating how modern technology can rescue and restore historically important works from the silent era.

Music

As a silent film, In the Land of the Head Hunters was originally accompanied by live musical performances during screenings. The original score has been lost, but it likely incorporated popular musical cues of the silent era. For the 1973 re-release under the title 'In the Land of the War Canoes,' a new musical score was composed by John J. B. Kelly and performed by the Kwakwaka'wakw group 'Ksan.' The 2013 restoration features a new musical score composed by Timothy Brock, which incorporates traditional Kwakwaka'wakw music and instruments alongside classical orchestration. This contemporary score attempts to bridge the gap between Curtis's early 20th-century sensibilities and modern appreciation for indigenous musical traditions. The soundtrack for the restoration includes field recordings of authentic Kwakwaka'wakw songs and chants, providing cultural context for the visual elements of the film.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, there are no spoken quotes, but the intertitles include: 'Motana, son of the chief, seeks the hand of Naida, daughter of the sorcerer.'

Intertitle: 'To win his bride, Motana must conquer the dreaded Gonakadet, monster of the deep.'

Intertitle: 'The war canoes of the Kwakwaka'wakw – swift as arrows, deadly as spears.'

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic sea monster sequence where Motana battles the Gonakadet, featuring innovative underwater photography and mechanical effects for the period.

- The elaborate potlatch ceremony showcasing authentic Kwakwaka'wakw dances, songs, and ceremonial regalia that had been banned by the Canadian government.

- The war canoe scenes with multiple canoes navigating the coastal waters of British Columbia, demonstrating traditional maritime skills.

- The totem pole carving sequence showing traditional techniques and designs, providing rare documentation of this cultural practice.

- The climactic battle scene between rival tribes, featuring authentic weapons and combat techniques from Kwakwaka'wakw tradition.

Did You Know?

- This was the first feature-length film with an entirely Native North American cast, predating Robert Flaherty's 'Nanook of the North' by eight years.

- Edward S. Curtis was primarily a photographer famous for his 20-volume work 'The North American Indian' before making this film.

- The film was originally titled 'In the Land of the Head Hunters' but was later re-released in 1973 as 'In the Land of the War Canoes' with a new musical score.

- Many of the ceremonial practices shown in the film had been banned by the Canadian government, making this film a rare visual record of these traditions.

- The film was considered lost for decades until a damaged copy was discovered in 1947 in the archives of the Field Museum in Chicago.

- The Kwakwaka'wakw actors wore authentic ceremonial regalia, some of which were centuries old and had been hidden from authorities.

- Curtis paid his Native actors $3 per day, which was a substantial sum at the time.

- The film's plot was loosely based on traditional Kwakwaka'wakw stories, though Curtis took significant dramatic liberties.

- The original film included color tinting for certain scenes, a common practice in the silent era.

- A complete restoration of the film was completed in 2013 using digital technology to repair damage and enhance the surviving footage.

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of the film were mixed, with many critics praising its visual beauty and exotic subject matter while questioning its authenticity and dramatic structure. The New York Times noted its 'picturesque qualities' but found the plot 'somewhat confusing.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film more favorably, recognizing its historical importance despite its ethnographic limitations. The 2013 restoration received widespread acclaim, with critics noting how the film transcends its ethnographic origins to create a visually stunning work of art. Scholars have highlighted the film's complex position between documentary and fiction, authentic performance and staged spectacle. While Curtis's romanticized vision and cultural misunderstandings have been criticized, the film's visual power and historical significance are now widely acknowledged.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception in 1914 was modest, as the film struggled to find commercial success despite its unique subject matter. Many viewers were drawn to its exotic imagery and authentic portrayal of Native American life, which differed dramatically from the stereotypical representations common in Hollywood films of the era. The film found more success in educational and anthropological circles than with general audiences. Following its rediscovery and restoration in the 21st century, the film has found new audiences among film enthusiasts, historians, and indigenous communities. Modern screenings, particularly those accompanied by live performances of traditional Kwakwaka'wakw music, have been well received, with audiences appreciating both the film's historical significance and its visual artistry.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Curtis's photographic work 'The North American Indian'

- Traditional Kwakwaka'wakw oral narratives

- Contemporary adventure films

- Ethnographic documentation practices

This Film Influenced

- Nanook of the North (1922)

- Man of Aran (1934)

- Moana (1926)

- Grass: A Nation's Battle for Life (1925)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for decades until a damaged 16mm copy was discovered in 1947 at the Chicago Field Museum. This incomplete version was missing several scenes and had deteriorated significantly. In 2008, a collaborative restoration project began involving the UCLA Film & Television Archive, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Cinémathèque Québécoise. The 2013 restoration combined elements from multiple sources including the original 35mm nitrate camera negative, the 16mm copy, and additional fragments discovered in other archives. The restoration has been digitally enhanced to repair damage and stabilize the image, though approximately one-third of the original footage remains lost. The restored version runs 65 minutes, shorter than the original runtime, which is believed to have been approximately 80-90 minutes.