Mabel's Blunder

Plot

Mabel, a young woman engaged to her boss's son, finds herself in an awkward position when her employer makes persistent unwanted advances toward her. To escape his attentions, Mabel disguises herself as a man, leading to a series of comedic misunderstandings and mistaken identities. The gender-bending scenario escalates when her fiancé fails to recognize her in disguise, creating a web of confusion that drives the slapstick comedy. The film culminates in a chaotic chase sequence where Mabel must maintain her disguise while trying to reunite with her true love and expose her boss's inappropriate behavior.

About the Production

This was one of the early films where Mabel Normand took on directing duties, showcasing her multifaceted talent in the male-dominated film industry of the 1910s. The film was shot quickly, typical of Keystone's rapid production schedule, with most scenes completed in one or two takes. The gender-bending elements were considered quite daring for the time period, reflecting the more permissive attitudes in early cinema before the Hays Code.

Historical Background

1914 was a pivotal year in cinema, occurring during the transition from short films to feature-length movies and before the establishment of the Hollywood studio system as it would later be known. This period saw the rise of comedy as a dominant genre, with Keystone Studios leading the field in slapstick innovation. The film was released just as World War I was beginning in Europe, though America's involvement would not come until 1917. In the film industry, 1914 marked the beginning of the exodus from New York to Los Angeles, with Keystone Studios being among the early establishments in what would become Hollywood. Women like Mabel Normand still had significant creative opportunities in the industry, a situation that would change dramatically by the 1920s.

Why This Film Matters

Mabel's Blunder represents an important milestone in early cinema as it showcases one of the few women directors of the silent era in action. The film's treatment of workplace harassment and female agency was remarkably progressive for its time, addressing themes that would remain relevant throughout cinema history. The gender-bending comedy elements prefigured later films that would use similar devices for social commentary. As a product of Keystone Studios, it exemplifies the rapid-fire, chaotic comedy style that would influence generations of comedians and filmmakers. The film also demonstrates the creative freedom that existed in early cinema before the imposition of censorship codes like the Hays Code, which would later restrict such content.

Making Of

Mabel Normand directed this film during her peak years at Keystone Studios, working closely with Mack Sennett who mentored her in directing. The production was typical of Keystone's fast-paced approach, with minimal scripting and heavy reliance on improvisation and physical comedy. Normand's dual role as director and star required her to direct scenes while also performing, a challenging feat that demonstrated her exceptional talent. The gender-bending elements required careful choreography to maintain the comedic effect while keeping the disguise believable within the context of silent film comedy. The film was shot on Keystone's Edendale studio lot, with exterior scenes filmed on the surrounding streets of Los Angeles, which were still relatively undeveloped at the time.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Frank D. Williams and Hans F. Koenekamp employed the straightforward, functional style typical of Keystone productions, with clear compositions designed to maximize the visibility of physical comedy. The camera work prioritized the performers' actions over artistic flourishes, using medium shots to capture full-body movements essential to the slapstick sequences. The film utilized the natural lighting available on the Keystone lot and Los Angeles locations, creating the bright, high-contrast look characteristic of early California filmmaking. The camera movement was minimal, relying instead on carefully choreographed performer movement within the frame to create visual interest.

Innovations

While not technologically innovative in terms of camera work or editing, the film demonstrated advanced narrative techniques for its period, particularly in its handling of mistaken identity and gender disguise. The continuity editing was more sophisticated than many contemporary films, maintaining clear spatial and temporal relationships despite the rapid pace. The film's success in making the gender disguise believable within the comedic context required careful attention to costume design and performance, representing an achievement in visual storytelling. The chase sequences, though standard for Keystone, showed efficient use of multiple locations and extras to create the illusion of a sprawling pursuit.

Music

As a silent film, Mabel's Blunder would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its original theatrical run. The typical Keystone score would have consisted of popular songs of the era, classical pieces, and original improvisations by the theater's pianist or organist. The music would have been synchronized to enhance the comedic timing, with faster tempos during chase sequences and more romantic themes during the scenes between Mabel and her fiancé. No original score has survived, though modern restorations are typically accompanied by newly composed period-appropriate music.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles. No specific quotes from the intertitles have been widely documented as particularly memorable, though the visual gags and physical comedy were the primary vehicles for the film's humor.

Memorable Scenes

- The transformation scene where Mabel disguises herself as a man, complete with suit, hat, and mustache, which was considered quite daring for 1914. The chase sequence through the Keystone studio lot, where Mabel in disguise must evade both her boss and her confused fiancé while maintaining her masculine persona. The climactic reveal scene where the disguise comes off, leading to the resolution of the various misunderstandings and the exposure of the boss's inappropriate behavior.

Did You Know?

- This was one of the first films where Mabel Normand was credited as both director and star, establishing her as a pioneering woman in early Hollywood

- The film showcases early examples of gender-bending comedy that would become more common in later decades

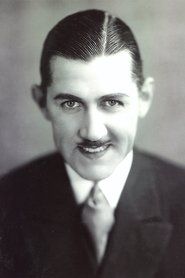

- Harry McCoy, who plays the lecherous boss, was a frequent collaborator with both Mabel Normand and Mack Sennett

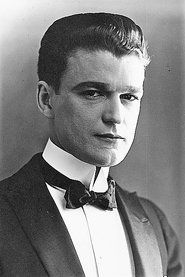

- Charley Chase appears under his real name Charles Parrott in this early role before becoming a comedy star in his own right

- The film was produced during Keystone's most prolific period, when the studio was releasing multiple short films per week

- Mabel Normand was one of the few women in early cinema to achieve both critical and commercial success as a director

- The film's themes of workplace harassment were remarkably progressive for 1914

- Keystone Studios was known for its chaotic comedic style, which is fully displayed in this film's chase sequences

- The preservation of this film is particularly valuable as it showcases Normand's directorial style, much of which has been lost due to film deterioration

- The film's success led to more directing opportunities for Normand, though she eventually focused primarily on acting

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews praised the film for its clever premise and Mabel Normand's dual talents as both director and performer. Variety noted the film's 'ingenious plot' and 'excellent execution' while highlighting Normand's 'natural comedic timing.' Modern film historians recognize the work as an important example of early female directorship and a sophisticated comedy that transcended typical Keystone fare. Critics have pointed out the film's subtle social commentary on gender dynamics and workplace power structures, elements that give it depth beyond its slapstick surface. The film is now regarded as one of Normand's most significant directorial efforts and a valuable artifact of early feminist cinema.

What Audiences Thought

The film was well-received by contemporary audiences who appreciated Normand's comedic talents and the film's clever premise. Theater audiences responded particularly well to the gender-bending elements and the chaotic chase sequences that were hallmarks of Keystone comedies. The film's success at the box office helped cement Normand's status as one of the most popular comediennes of the era. Modern audiences who have seen the film through screenings at film archives and festivals have noted its surprisingly progressive themes and sophisticated humor that holds up remarkably well over a century later.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Keystone comedy style

- Mack Sennett's production methods

- French and Italian slapstick traditions

- Stage comedy conventions of the 19th century

This Film Influenced

- Later gender-bending comedies

- Workplace romance films

- Slapstick chase sequences in sound films

- Comedies featuring female protagonists in male disguise

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has survived and is preserved in several film archives, including the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. While some deterioration is evident, the film remains largely intact and viewable. It has been included in several DVD collections of Keystone comedies and Mabel Normand's work. The preservation of this film is particularly significant as it represents one of the few surviving examples of Mabel Normand's work as a director.