Mantrap

"The Girl Who Was Too Much for Any Man!"

Plot

Alverna, a vivacious young manicurist from Minneapolis, impulsively marries Joe Easter, a gentle giant of a backwoodsman, and moves with him to the remote Canadian wilderness. When Ralph Prescott, a sophisticated and wealthy New York divorce lawyer, arrives on vacation, Alverna becomes instantly infatuated with his urban charm and refinement. Bored with her primitive existence, she follows Ralph back to civilization, only to discover that the sophisticated world she craved may not bring her the happiness she expected. The film culminates in a complex emotional triangle where Alverna must choose between the simple, devoted love of her husband and the exciting but potentially hollow allure of city life. Through this journey, the story explores themes of authenticity versus artificiality and the search for genuine connection.

About the Production

The film was shot on location in the Sierra Nevada mountains to authentically depict the Canadian wilderness setting. Director Victor Fleming insisted on real outdoor shooting rather than studio backdrops to capture the contrast between civilization and nature. The production faced challenges with weather conditions during location shooting, with unexpected snowfall requiring schedule adjustments. Clara Bow performed many of her own stunts, including scenes near rushing water and on rough terrain. The film was rushed into production to capitalize on Bow's growing popularity from her recent success in 'The Plastic Age' (1925).

Historical Background

1926 was a pivotal year in American cinema, representing the height of the silent film era just before the transition to sound. The Roaring Twenties were in full swing, with flapper culture, jazz music, and changing social mores reflected in popular entertainment. This film emerged during a period of significant social change, when women's roles were evolving and the tension between traditional values and modern lifestyles was a prominent cultural theme. The year also saw the rise of the studio system, with Paramount Pictures establishing itself as a major force in Hollywood. The film's release coincided with the publication of Sinclair Lewis's novel, capturing the public's fascination with the contrast between urban sophistication and rural authenticity that defined much of 1920s American literature and cinema.

Why This Film Matters

'Mantrap' holds significant cultural importance as a defining film of the Jazz Age and a crucial work in establishing Clara Bow as the quintessential flapper icon. The film perfectly captured the spirit of the 1920s, embodying the era's fascination with modernity, sexual liberation, and the clash between traditional and contemporary values. It helped codify the 'flapper' archetype in cinema, influencing countless subsequent films and popular culture representations of 1920s women. The movie's exploration of female agency and desire, though somewhat constrained by era conventions, was progressive for its time and reflected the changing role of women in American society. Its success demonstrated the commercial viability of films centered on strong, independent female protagonists, paving the way for more women-centered narratives in Hollywood.

Making Of

The production of 'Mantrap' was marked by significant tension between Clara Bow and director Victor Fleming, who initially doubted her acting abilities but was ultimately impressed by her natural talent and screen presence. Bow, who came from a troubled Brooklyn background, found an unlikely mentor in Ernest Torrence, who helped her with dramatic scenes. The film's wilderness sequences were particularly challenging to shoot, with the cast and crew enduring primitive conditions for authenticity. Fleming, known for his demanding directing style, pushed Bow to deliver more nuanced performances beyond her typical flapper roles. The chemistry between Bow and her co-stars was genuine, with Torrence's paternal off-screen relationship with Bow translating perfectly to their on-screen dynamic. The film's success surprised Paramount executives, who had initially considered it a minor production but quickly recognized its potential after seeing early footage.

Visual Style

The cinematography by James Wong Howe employed innovative techniques for both studio and location shooting, creating a visual contrast between the sophisticated urban environments and the rugged wilderness. Howe utilized natural lighting extensively in the outdoor sequences, particularly in the mountain locations, to enhance the authenticity of the backwoods setting. The film featured notable tracking shots and camera movements that were advanced for the period, especially during the chase sequences through the forest. The visual style emphasized the contrast between the confined, artificial spaces of the city and the expansive, natural landscapes of the wilderness, using lighting and composition to reinforce the film's thematic concerns. Howe's work on this film demonstrated his mastery of both studio lighting and location cinematography, techniques that would influence his later acclaimed work in sound films.

Innovations

While not groundbreaking in technical innovation, 'Mantrap' demonstrated notable advances in location shooting techniques and the integration of outdoor footage with studio scenes. The film's production team developed improved methods for transporting and operating camera equipment in rugged mountain terrain, techniques that would influence subsequent location-based productions. The seamless blending of location footage with studio-interior scenes was particularly impressive for the period, with careful attention to lighting consistency and continuity. The film also featured sophisticated editing techniques for its chase sequences and romantic montages, using cross-cutting and parallel action to build tension and emotional impact. The sound recording techniques used for the musical accompaniment in larger theaters were also notably advanced for the period.

Music

As a silent film, 'Mantrap' was accompanied by a musical score compiled from various classical and popular pieces, with theater organists or small orchestras providing live accompaniment during screenings. The original cue sheets suggested music ranging from classical composers like Mendelssohn and Tchaikovsky to contemporary popular songs of the 1920s. The score emphasized the emotional contrasts in the story, using lively jazz-influenced pieces for scenes with Alverna and more traditional melodies for the wilderness sequences. Paramount provided detailed musical direction to theaters to ensure consistent emotional impact across different venues. The musical accompaniment played a crucial role in conveying the film's comedic and romantic elements, particularly in scenes where Clara Bow's expressive performance needed musical support to enhance the emotional resonance.

Famous Quotes

Intertitle: 'She was a human mantrap - and every man was her victim!'

Intertitle: 'In the wilderness, a man can find himself - or lose himself!'

Intertitle: 'City lights or starlight - which would you choose?'

Intertitle: 'Sometimes the cage you fly to is smaller than the one you left!'

Memorable Scenes

- Clara Bow's energetic introduction as the vivacious manicurist, establishing her character's charm and flirtatious nature

- The dramatic wilderness chase sequence where Alverna follows Ralph through the rugged Canadian landscape

- The poignant confrontation scene where Joe Easter discovers Alverna's desire to leave for the city

- The sophisticated city party scene where Alverna feels out of place among Ralph's worldly friends

- The emotional climax where Alverna must choose between her two very different worlds

Did You Know?

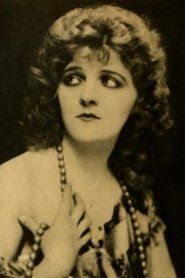

- This film was Clara Bow's first major starring role and helped establish her as 'The It Girl' of the 1920s

- Based on the 1926 novel of the same name by Sinclair Lewis, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1930

- The film's success led to Clara Bow receiving a $5,000 per week contract, making her one of the highest-paid actresses in Hollywood

- Ernest Torrence, who played Joe Easter, was a classically trained opera singer before turning to acting

- The film was one of the first to prominently feature the 'flapper' archetype that would define 1920s cinema

- Victor Fleming later directed such classics as 'The Wizard of Oz' and 'Gone with the Wind'

- The film's title 'Mantrap' refers both to the literal wilderness setting and metaphorically to Alverna's captivating effect on men

- Sinclair Lewis reportedly disliked the film adaptation, feeling it oversimplified his novel's social commentary

- The movie was remade in 1931 as 'Mantrap' with a different cast, but the 1926 version is considered superior

- Clara Bow's performance in this film directly led to her casting in the iconic film 'It' (1927), which cemented her 'It Girl' status

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Mantrap' for its entertainment value and Clara Bow's magnetic performance, with Variety calling it 'a thoroughly enjoyable picture with plenty of action and romance.' The New York Times highlighted Bow's 'vital and spirited' performance, noting her natural charisma and screen presence. Modern critics have reassessed the film as an important transitional work in Bow's career and a significant example of 1920s comedy-drama. Film historians appreciate its faithful adaptation of Sinclair Lewis's themes while maintaining broad commercial appeal. The film is now recognized as a key text in understanding the evolution of the romantic comedy genre and the representation of women in silent cinema.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences embraced 'Mantrap' enthusiastically, making it one of the biggest box office hits of 1926. Clara Bow's performance resonated particularly strongly with young women who identified with her character's independence and vitality. The film's blend of comedy, romance, and outdoor adventure appealed to a broad demographic, from urban sophisticates to rural viewers. Movie theaters reported packed houses and repeat viewings, with many fans specifically drawn to see the rising star who would soon be dubbed 'The It Girl.' The film's success established a loyal fan base for Bow that would sustain her career through the transition to sound. Contemporary audience letters and fan magazines reveal that viewers were particularly captivated by the on-screen chemistry between Bow and her co-stars, as well as the film's stunning location photography.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards were given for this film, as the Academy Awards were not established until 1929

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Sinclair Lewis's novel 'Mantrap' (1926)

- Contemporary romantic comedies of the 1920s

- The literary tradition of nature vs. civilization narratives

- The growing flapper culture of the Jazz Age

This Film Influenced

- 'It' (1927) - Clara Bow's subsequent breakout role

- Subsequent romantic comedies featuring independent female protagonists

- Films exploring urban-rural contrasts

- Later adaptations of Sinclair Lewis works

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in complete form and has been preserved by major film archives including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. A restored version was released on DVD by Kino Lorber as part of their Clara Bow collection, featuring a new musical score. While some wear is evident in existing prints, the overall visual quality is quite good for a film of its vintage. The restoration work has particularly enhanced the clarity of the location footage, bringing out the beauty of the wilderness photography.