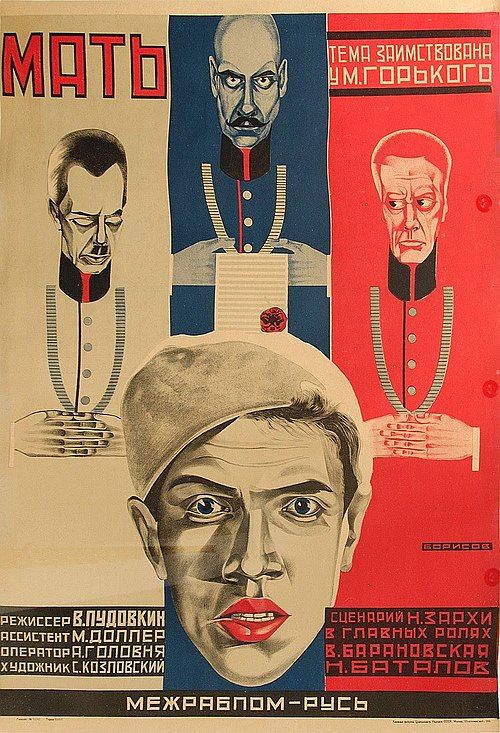

Mother

Plot

Pelageya Nilovna Vlasova is a simple, uneducated woman living in pre-revolutionary Russia who initially supports her husband's conservative, anti-revolutionary views. When her son Pavel becomes involved in revolutionary activities against the Tsarist regime, she finds herself torn between her traditional loyalty to her husband and her growing love for her son. After Pavel is arrested and imprisoned for his political activities, the mother undergoes a profound political awakening, transforming from a passive observer into an active participant in the revolutionary movement. The film culminates powerfully with the mother joining a workers' demonstration and carrying the red flag, symbolizing her complete transformation and commitment to the revolutionary cause. Throughout the narrative, Pudovkin masterfully depicts the mother's internal struggle and eventual liberation, using her personal journey as an allegory for the broader transformation of Russian society during the revolution.

About the Production

Based on Maxim Gorky's 1906 novel of the same name. Pudovkin adapted the novel with significant changes to emphasize the revolutionary message. The film was shot during a period of intense creative experimentation in Soviet cinema. Production took approximately 6-8 months, which was typical for the era. The factory scenes were filmed in actual industrial settings to achieve maximum authenticity. Pudovkin insisted on using real workers as extras in the demonstration scenes to enhance the film's documentary-like quality.

Historical Background

Mother was produced during the NEP (New Economic Policy) period in Soviet history, a time of relative artistic freedom before Stalin's strict socialist realism mandates took effect. The film emerged from the golden age of Soviet cinema when revolutionary filmmakers like Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Vertov were experimenting with the language of cinema itself. It was created to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the 1917 Revolution and served both as artistic expression and political education. The film reflected the Soviet government's efforts to create a new cinematic language that would serve revolutionary ideals. During this period, the Soviet film industry was state-controlled but allowed considerable creative experimentation, leading to some of the most innovative films in cinema history. The film's production coincided with debates about the proper role of art in building socialism, with Pudovkin advocating for cinema that could emotionally move audiences toward revolutionary consciousness.

Why This Film Matters

Mother is considered a cornerstone of Soviet cinema and one of the most influential silent films ever made. It helped establish montage as a fundamental cinematic technique and influenced generations of filmmakers worldwide. The film's use of a personal story to illustrate broader political themes became a template for politically engaged cinema. Its visual style and editing techniques were studied and emulated by filmmakers from Jean-Luc Godard to Stanley Kubrick. The film demonstrated how cinema could combine emotional storytelling with political messaging without sacrificing artistic quality. It established Pudovkin as one of the three great Soviet montage theorists alongside Eisenstein and Vertov. The film's influence extended beyond cinema to other art forms, influencing how artists approached the relationship between individual experience and historical change. It remains a key text in film studies programs worldwide and continues to be analyzed for its innovative techniques and powerful emotional impact.

Making Of

Pudovkin approached 'Mother' as both an artistic and ideological project, believing cinema could serve as a tool for social education and revolutionary propaganda. He developed a unique editing style that contrasted with Eisenstein's approach, focusing more on psychological development through associative montage rather than intellectual montage. The famous scene where the mother imagines her son in prison was created through innovative superimposition techniques. Pudovkin spent months preparing his actors, particularly Vera Baranovskaya, using exercises derived from Stanislavski's system to achieve naturalistic performances. The factory demonstration sequence involved hundreds of extras and was choreographed like a military operation to achieve the desired visual impact. Pudovkin insisted on multiple takes of key emotional scenes, pushing his actors to exhaustion to capture authentic emotional responses. The ice-breaking sequence required dangerous filming conditions with actors working in freezing temperatures to achieve realism.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Anatoli Golovnya was revolutionary for its time, featuring innovative camera movements and compositions that enhanced the psychological drama. Golovnya employed dynamic tracking shots during the demonstration sequences and used unusual camera angles to emphasize the mother's changing perspective. The film's visual style evolved from static, composed shots in the early scenes to more dynamic, mobile cinematography as the mother becomes politically awakened. The famous ice-breaking sequence used multiple cameras and creative angles to create a metaphor for revolutionary force. Golovnya experimented with focus and depth of field to create visual hierarchies that guided viewers' attention to key emotional elements. The film's black and white photography featured rich tonal contrasts that enhanced the dramatic impact of key scenes, particularly the prison sequences and the final demonstration.

Innovations

Mother pioneered several technical innovations that became standard in cinema. Pudovkin developed what he called 'relational editing,' where shots were linked not just by content but by emotional and psychological associations. The film featured innovative use of superimposition to represent internal psychological states, particularly in the mother's dream sequences. The ice-breaking scene demonstrated groundbreaking special effects using combination printing and multiple exposure techniques. Pudovkin experimented with varying shot lengths to control emotional rhythm, using shorter cuts during moments of tension and longer takes for emotional reflection. The film's structure, divided into five distinct episodes, influenced narrative approaches in both Soviet and international cinema. The demonstration sequences featured complex crowd choreography that required precise timing and coordination, setting new standards for mass scenes in film.

Music

As a silent film, Mother was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater. The original Soviet score was composed by Vladimir Deshevov and emphasized Russian folk themes combined with modernist elements to reflect the film's blend of traditional and revolutionary themes. The score used leitmotifs to represent different characters and ideas, with the mother's theme evolving from simple, melodic passages to more complex, triumphant arrangements as she undergoes her transformation. Modern restorations have featured newly composed scores by artists such as Timothy Brock, who created orchestral arrangements that respect the film's Soviet origins while appealing to contemporary audiences. The original musical cues emphasized percussive elements during the demonstration scenes to create rhythmic momentum, while using more lyrical passages for the intimate family moments.

Famous Quotes

"Don't be afraid, mother. The truth is stronger than the Tsar." - Pavel to his mother

"I was blind, but now I see." - The mother during her political awakening

"The ice is breaking! The ice is breaking!" - Chanted during the demonstration sequence

Memorable Scenes

- The ice-breaking sequence where workers use their collective strength to break through frozen river ice, serving as a powerful metaphor for revolutionary force

- The mother's nightmare sequence where she imagines her son suffering in prison, using innovative superimposition techniques

- The final demonstration scene where the mother transforms from passive observer to active participant by seizing the red flag

- The prison visitation scene where the mother's political awakening begins through her son's revolutionary teachings

- The factory strike sequence that showcases Pudovkin's mastery of crowd choreography and dynamic editing

Did You Know?

- Director Vsevolod Pudovkin was a student of Lev Kuleshov and helped develop the influential Kuleshov effect theory of montage

- The film was considered lost for decades before being rediscovered and restored in the 1960s

- Vera Baranovskaya, who played the mother, was a theater actress making her film debut

- Pudovkin wrote a seminal book on film theory titled 'Film Technique and Film Acting' where he used 'Mother' as a primary example

- The film's structure follows five distinct episodes: 'The Meeting,' 'The Home,' 'The Arrest,' 'The Trial,' and 'The Street Demonstration'

- Maxim Gorky, the author of the source novel, personally approved Pudovkin's adaptation despite significant changes from the book

- The famous ice-breaking scene was created using special effects involving glass and clever editing techniques

- The film was banned in several countries including the United States until the 1930s due to its revolutionary content

- Pudovkin cast non-professional actors for many of the worker roles to achieve greater authenticity

- The red flag in the final scene was actually white during filming and colored red through tinting in post-production

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised Mother as a masterpiece of revolutionary art, with particular admiration for its emotional power and technical innovation. Western critics initially had mixed reactions due to political biases, but over time recognized its artistic merits. The film was championed by influential critics like André Bazin, who praised its psychological depth and emotional authenticity. Modern critics consistently rank it among the greatest films of the silent era, with particular appreciation for Pudovkin's sophisticated use of montage to develop character psychology rather than merely create intellectual juxtapositions. The film is frequently cited in academic studies for its innovative narrative structure and visual storytelling techniques. Contemporary film scholars often compare it favorably with Eisenstein's 'Battleship Potemkin' as an alternative approach to revolutionary cinema that emphasizes individual transformation over collective action.

What Audiences Thought

Soviet audiences in 1926 responded enthusiastically to Mother, with many reporting that it helped them understand the revolutionary struggle through its personal, emotional approach. The film was particularly popular among workers and peasants who could identify with the mother's journey from political ignorance to revolutionary consciousness. International audiences were initially limited due to political barriers, but where it was shown, it often received strong responses for its emotional power. The film's success led to increased demand for similar works that combined political messaging with personal drama. Over the decades, audiences at revival screenings have continued to respond strongly to the film's emotional core and technical brilliance. Modern audiences often report being surprised by how contemporary the film feels despite its age, particularly its sophisticated editing and emotional storytelling.

Awards & Recognition

- Named one of the Top 12 Greatest Films of All Time by the Brussels World's Fair (1958)

- Voted Best Film of the Year by Soviet critics (1926)

- Honored at the First International Film Festival in Moscow (1935)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Maxim Gorky's novel 'Mother' (1906)

- Lev Kuleshov's montage theory

- D.W. Griffith's narrative techniques

- German Expressionist cinema

- Soviet constructivist art

- Stanislavski's acting system

This Film Influenced

- The End of St. Petersburg (1927)

- Storm Over Asia (1928)

- The New Babylon (1929)

- October: Ten Days That Shook the World (1928)

- The General Line (1929)

- Zemlya (1930)

- The Battleship Potemkin (1925) - in terms of revolutionary cinema development

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was believed lost for many years but was rediscovered in the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow. It has been fully restored by several archives including the Museum of Modern Art and the British Film Institute. The most recent restoration was completed in 2005 using original negatives and multiple print sources to create the most complete version available. The restored version includes tinted sequences that match the original 1926 release. The film is preserved in the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress for its cultural and historical significance.