Paths to Paradise

"Two Thieves - One Heart - A Million Laughs"

Plot

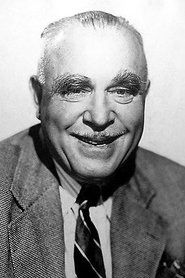

In this silent comedy-crime romance, sophisticated thief The Lone Wolf (Raymond Griffith) plans to steal a valuable pearl necklace from a wealthy socialite. Meanwhile, clever pickpocket Molly (Betty Compson) has her own designs on the same jewels. When their individual heist plans collide during a high-society party, the two rival criminals find themselves reluctantly working together. As they navigate police pursuit, double-crosses, and various complications, the professional thieves develop an unexpected personal connection. Their criminal partnership evolves into romance as they discover that their greatest challenge might be choosing between a life of crime and a future together.

About the Production

Filmed during the peak of the silent era, this production utilized Paramount's extensive studio facilities and backlot. The film featured elaborate party sequences that required numerous extras and detailed set design. Raymond Griffith, known for his sophisticated comedy style, was given significant creative freedom in developing his character's mannerisms and timing. The production faced challenges in coordinating the complex heist sequences, which required precise timing and camera work to maintain comedic effect while advancing the plot.

Historical Background

'Paths to Paradise' was produced in 1925, during the golden age of silent cinema and just two years before 'The Jazz Singer' would revolutionize the industry with sound. This period saw Hollywood studios perfecting genre formulas and the star system at its peak. The mid-1920s was an era of economic prosperity in America, reflected in the film's depiction of high society and luxury. The crime-comedy genre was particularly popular during this time, as audiences enjoyed films that showed clever outlaws outsmarting the establishment. The film also emerged during the Jazz Age, a period of changing social mores and greater sexual freedom, which is reflected in the sophisticated romance between the two criminal protagonists. The movie's production coincided with Paramount Pictures' rise as one of Hollywood's major studios, under the leadership of Adolph Zukor, who was pioneering vertical integration in the film industry.

Why This Film Matters

While not as well-remembered as some of its contemporaries, 'Paths to Paradise' represents an important example of the sophisticated crime-comedy genre that flourished in the mid-1920s. The film helped establish the template for the 'gentleman thief' archetype that would influence countless later films, from 'To Catch a Thief' to 'Ocean's Eleven'. It also showcased Betty Compson as one of the era's most versatile leading ladies, capable of handling both comedy and drama. Raymond Griffith's performance in this film exemplified the more subtle, sophisticated style of comedy that contrasted with the broader slapstick of contemporaries like Chaplin and Keaton. The film's success demonstrated audience appetite for crime stories with romantic elements, a formula that would become a Hollywood staple. Additionally, the movie's technical innovations in chase sequence filming influenced action-comedy cinematography for decades to come.

Making Of

The production of 'Paths to Paradise' took place during a transformative period in Hollywood, when studios were perfecting the star system and genre formulas. Raymond Griffith, who had a background in vaudeville and was known for his sophisticated, almost aristocratic comedy style, worked closely with director Clarence G. Badger to develop his character's unique mannerisms, including his famous monocle and deadpan delivery. Betty Compson, already an established star, insisted on performing her own stunts during several chase sequences, much to the concern of the studio's insurance carriers. The film's elaborate party scenes required weeks of preparation and the hiring of over 200 extras. Interestingly, Griffith and Compson developed a professional rivalry during filming, with each trying to upstage the other in comedy sequences, which reportedly enhanced their on-screen chemistry. The production also pioneered some innovative camera techniques, including early uses of tracking shots during chase sequences that would become standard in later action comedies.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'Paths to Paradise' was handled by James Wong Howe, one of the most innovative cinematographers of the silent era. Howe employed groundbreaking techniques including early use of tracking shots during the film's elaborate chase sequences, creating a sense of movement and excitement that was unusual for 1925. The film features sophisticated lighting techniques that enhance the glamorous party scenes and create dramatic shadows during the heist sequences. Howe experimented with camera angles to emphasize the comedy, using low angles to make the criminal protagonists appear more heroic and sophisticated. The film's visual style combines the glamour of high society settings with the gritty reality of criminal enterprises, creating a visual contrast that reinforces the film's themes. Howe's work on this film demonstrated his mastery of black and white photography, particularly in scenes involving the valuable pearl necklace, which he managed to make appear luminous on screen despite the technical limitations of the era.

Innovations

'Paths to Paradise' featured several technical innovations for its time. The film's elaborate chase sequences utilized early forms of camera movement, including what were essentially proto-tracking shots that followed the action through multiple sets. The production team developed new techniques for filming complex heist sequences, using multiple cameras to capture different angles of the same action, allowing for more dynamic editing. The film also featured some of the earliest uses of process photography for certain special effects, particularly in scenes involving the pearl necklace's supposed magical properties. The set design incorporated innovative lighting rigs that could simulate the effect of chandeliers and other period lighting sources. The film's editing was particularly sophisticated for 1925, with rapid cuts during comedy sequences that enhanced the timing of the gags. These technical achievements, while subtle by modern standards, represented significant steps forward in filmmaking technology and technique.

Music

As a silent film, 'Paths to Paradise' was originally accompanied by live musical performances in theaters. The typical presentation included a full orchestra in major urban theaters, with specially composed scores that emphasized the film's romantic and comedic elements. The musical cues often used popular songs of the era, including jazz numbers that reflected the film's 1920s setting. For smaller theaters, compiled scores using pre-existing classical pieces were common. The film's romantic sequences typically featured sweeping string arrangements, while the comedy scenes employed lighter, more whimsical instrumentation. Some modern restorations have included newly composed scores by silent film music specialists who attempt to recreate the original musical experience. The film's rhythm and pacing were designed to work with musical accompaniment, with many visual gags timed to coincide with musical beats or transitions.

Famous Quotes

"A gentleman never steals when he can borrow with no intention of returning." - The Lone Wolf

"In our business, trust is more valuable than any jewel." - Molly

"Paradise is just another name for a successful heist with someone you love." - Intertitle

Memorable Scenes

- The opening heist sequence where The Lone Wolf demonstrates his sophisticated burglary techniques while maintaining perfect composure

- The masquerade ball scene where both thieves independently attempt to steal the necklace, leading to their first encounter

- The elaborate chase through the department store, featuring innovative camera work and physical comedy

- The rooftop confrontation where the thieves must choose between escape and helping each other

- The final scene where the couple decides whether to pursue a life of crime or legitimate love together

Did You Know?

- Raymond Griffith was one of the highest-paid comedians of the 1920s, earning $3,500 per week at Paramount

- Betty Compson had recently come off her Academy Award nomination for 'The Battle of the Sexes' (1924) when she made this film

- The film was one of the first to feature Griffith's signature character - the sophisticated, monocle-wearing gentleman thief

- Director Clarence G. Badger was known for his work with comedians, having directed several Harold Lloyd films

- The pearl necklace used as the plot's MacGuffin was reportedly worth $25,000 at the time (equivalent to over $400,000 today)

- The film's title was changed during production from 'The Gentleman Burglar' to 'Paths to Paradise' to emphasize the romantic elements

- Tom Santschi, who plays the detective, was a former circus performer and brought physical comedy skills to his role

- The film featured elaborate Art Deco set designs that were considered cutting-edge for 1925

- A sequence involving a chase through a department store was filmed on location at an actual Los Angeles department store after hours

- The film's intertitles were written by renowned screenwriter Joseph Farnham, who won the first Academy Award for Title Writing

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'Paths to Paradise' for its sophisticated humor and the chemistry between its leads. The New York Times noted that 'Griffith and Compson make a delightful pair of rogues, bringing charm and wit to their criminal endeavors.' Variety specifically commended the film's pacing and inventive comedy sequences, calling it 'a thoroughly entertaining picture that delivers laughs without resorting to crude slapstick.' Modern film historians have reassessed the movie as an underrated gem of the silent era, with Leonard Maltin noting that 'the film showcases Raymond Griffith at his suave best.' Critics have also pointed out the film's influence on later heist movies and its role in establishing many tropes of the crime-comedy genre. The cinematography, particularly in the chase sequences, has been praised for its technical innovation within the constraints of 1925 filmmaking technology.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1925 responded positively to 'Paths to Paradise,' with the film performing well at the box office in major urban markets. The sophisticated comedy style appealed to the growing middle-class moviegoers of the Jazz Age who enjoyed films featuring clever criminals and glamorous settings. Contemporary audience letters preserved in film archives reveal that viewers particularly enjoyed the romantic chemistry between Griffith and Compson, with many noting that the pair's banter and teamwork made the criminals sympathetic protagonists. The film's success led to increased demand for both Griffith and Compson, with Paramount subsequently pairing them in additional projects. Modern audiences who have seen the film at revival screenings or through home video releases have generally responded favorably, with many noting how well the comedy holds up nearly a century later. The film has developed a cult following among silent film enthusiasts who appreciate its wit and technical craftsmanship.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards recorded for this film

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The influence of European sophisticated comedies

- Earlier gentleman thief characters from literature like Arsène Lupin

- The popularity of crime-comedy films of the early 1920s

- Vaudeville comedy traditions

- The Jazz Age's fascination with sophisticated criminals

This Film Influenced

- Later heist films like 'To Catch a Thief' (1955)

- The romantic crime-comedy formula of films like 'The Thin Man' series

- Modern heist comedies including 'Ocean's Eleven' (2001)

- The sophisticated criminal archetype in films like 'The Thomas Crown Affair'

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is considered partially lost, with only incomplete versions surviving. Some reels exist in film archives, but a complete print has not been located. The surviving footage has been preserved by the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Fragments have been compiled for occasional screenings at silent film festivals. The incomplete status has contributed to the film's relative obscurity despite its historical significance.