Quo Vadis?

"The Greatest Spectacle Ever Filmed - Rome in All Her Glory and Shame"

Plot

Set during the tyrannical reign of Emperor Nero in ancient Rome, the film follows Marcus Vinicius, a Roman military commander who becomes infatuated with Lygia, a beautiful Christian hostage living in the household of a retired general. Despite her Christian faith and the protection of her devoted guardian Ursus, Vinicius attempts to possess Lygia, leading him to infiltrate the Christian community in the catacombs where he witnesses their secret prayer meetings led by the Apostle Peter. As Vinicius experiences a spiritual awakening and begins to question his pagan beliefs, Nero orchestrates the devastating Great Fire of Rome and scapegoats the Christians, subjecting them to brutal persecution in the arena. The film culminates in spectacular sequences of Christian martyrdom, including the iconic scene of Lygia being saved from a bull by the superhuman strength of Ursus, while Vinicius must choose between his loyalty to Rome and his newfound love and faith. The narrative concludes with the apostle Peter's martyrdom and the enduring legacy of Christian sacrifice in the face of imperial oppression.

About the Production

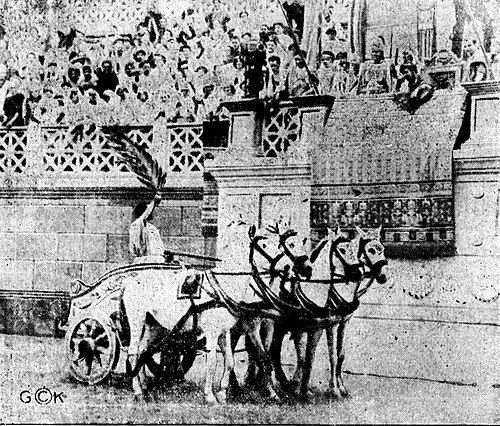

The production involved over 5,000 extras, massive sets including a full reconstruction of ancient Rome, and groundbreaking special effects. The famous arena sequences were filmed using real animals and innovative camera techniques. The production took nearly a year to complete, with meticulous attention to historical accuracy in costumes and props. The fire of Rome sequence was one of the most expensive and dangerous sequences filmed to date, requiring extensive safety precautions and innovative fire effects.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the golden age of Italian cinema, when the country was establishing itself as a dominant force in global filmmaking. 1913 was a period of tremendous cultural and artistic flowering in Italy, with the Futurist movement challenging traditional artistic conventions and the nation still reveling in its recent unification. The film's focus on early Christianity and Roman persecution resonated with contemporary audiences, as tensions between church and state remained significant in Italian society. The massive scale of the production reflected Italy's ambitions to compete with other European powers not just economically and militarily, but culturally as well. The film's emphasis on spectacle and historical grandeur also tapped into growing nationalist sentiments that would later contribute to the rise of fascism. The timing was particularly significant as it predated World War I, which would dramatically alter the European film landscape and end Italy's dominance in international cinema.

Why This Film Matters

'Quo Vadis?' revolutionized the film industry by establishing the template for the historical epic, a genre that would dominate cinema for decades. Its success proved that audiences would embrace long, complex narratives with sophisticated production values, paving the way for feature-length films to become the industry standard. The film's innovative techniques in set design, crowd scenes, and special effects influenced countless subsequent productions, most notably Giovanni Pastrone's 'Cabiria' (1914) and D.W. Griffith's 'Intolerance' (1916). It also established Italy as the epicenter of epic filmmaking, a position it would maintain throughout the silent era. The film's treatment of religious themes and historical events demonstrated cinema's capacity to handle serious, weighty subject matter, elevating the medium's cultural status. Its international success helped create a global market for films, proving that cinema could transcend language barriers. The film's visual vocabulary would be copied and refined for decades, influencing everything from Cecil B. DeMille's biblical epics to modern blockbusters like 'Gladiator'.

Making Of

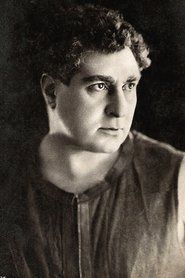

The production of 'Quo Vadis?' was an unprecedented undertaking for its time, requiring innovations in nearly every aspect of filmmaking. Director Enrico Guazzoni insisted on historical authenticity, consulting with historians and archaeologists to ensure accuracy in costumes, architecture, and customs. The massive sets were constructed on the outskirts of Rome, including a partial reconstruction of the Colosseum that could accommodate thousands of extras. The fire sequence was particularly challenging, requiring careful coordination between the special effects team and actors. The cast underwent extensive training, with Bruto Castellani (Ursus) undertaking physical preparation to convincingly portray the character's legendary strength. The film's success led to Guazzoni becoming one of Italy's most celebrated directors, though he struggled to replicate its success with subsequent projects. The production also pioneered techniques in crowd control and extras management, developing systems that would become standard in epic filmmaking.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Alessandro B. San Severino was groundbreaking for its time, featuring innovative camera movements and compositions that enhanced the film's epic scope. The use of deep focus allowed for spectacular crowd scenes with thousands of extras, while careful lighting created dramatic contrasts between the opulent Roman settings and the shadowy catacombs. The film employed traveling shots during action sequences, particularly in the battle and arena scenes, creating a sense of movement and energy rarely seen in cinema of this era. The cinematography also featured elaborate tracking shots that followed characters through massive sets, helping to establish the scale of the production. The fire sequence utilized innovative techniques including multiple exposures and careful color tinting to enhance the dramatic effect. The visual style combined documentary-like realism in the crowd scenes with romantic, painterly compositions for the intimate moments between the main characters. The cinematography's influence can be seen in subsequent epics, particularly in how it balanced spectacle with human emotion.

Innovations

The film pioneered numerous technical innovations that would become standard in epic filmmaking. The massive sets were built using revolutionary construction techniques that allowed for rapid assembly and disassembly, enabling efficient use of studio space. The film utilized innovative matte painting techniques to extend the apparent size of sets and create the illusion of ancient Rome's grandeur. The special effects team developed new methods for creating realistic fire scenes, including controlled burning techniques and safety measures for actors and animals. The crowd scenes employed sophisticated choreography and camera positioning to create the illusion of even larger crowds than actually appeared. The film also featured early experiments with color tinting, particularly in the fire sequences and sunset scenes. The battle sequences utilized innovative camera mounting techniques that allowed for dynamic movement during action scenes. The production also developed new methods for coordinating thousands of extras, creating systems that would influence crowd management in films for decades. These technical achievements represented a significant leap forward in cinematic possibilities and helped establish the vocabulary of epic filmmaking.

Music

As a silent film, 'Quo Vadis?' was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater and location. The typical presentation included a full orchestra performing classical pieces alongside original compositions. The score often incorporated works by Verdi, Puccini, and other Italian composers to enhance the film's dramatic moments. Some theaters used organ accompaniment, while others employed full orchestras with specially commissioned music. The musical cues were carefully synchronized with the on-screen action, with different themes for the main characters and dramatic motifs for key scenes. The fire sequence was typically accompanied by thundering percussion and dramatic brass, while the Christian scenes featured more reverent, spiritual music. Modern restorations have been accompanied by newly composed scores that attempt to recreate the spirit of the original accompaniments while utilizing contemporary musical resources. The film's musical legacy includes its influence on how subsequent epics would use music to enhance their emotional impact and dramatic scope.

Famous Quotes

'Quo Vadis, Domine?' - Peter's question to Jesus on the Appian Way

'Rome burns while Nero fiddles!' - Contemporary description of the emperor's actions

'In the name of Christ, I will not renounce my faith!' - Lygia's defiance

'The blood of martyrs is the seed of the Church.' - Tertullian's quote referenced in the film

'Better to die for Christ than live for Nero!' - Christian rallying cry

Memorable Scenes

- The spectacular recreation of the Great Fire of Rome, with massive sets burning and thousands of extras fleeing in panic

- The arena sequence where Ursus saves Lygia from the bull through superhuman strength, one of cinema's first great action sequences

- The catacomb prayer meeting led by the Apostle Peter, creating an atmosphere of secret worship and spiritual intensity

- Lygia's baptism scene, with careful attention to the ritual's visual and emotional power

- Nero's decadent feast scenes, showcasing the excesses of imperial Rome with elaborate costumes and sets

- Peter's martyrdom sequence, filmed with reverent solemnity and dramatic power

- The final confrontation between Vinicius and Nero, representing the clash between Christian values and imperial corruption

Did You Know?

- This was the first film adaptation of Henryk Sienkiewicz's 1896 novel, which would later be adapted multiple times, most famously in 1951

- The film's success led to a boom in Italian historical epics, creating what became known as the 'sword and sandal' genre

- The arena sequences used real lions and other animals, though careful safety measures were implemented

- The film was so expensive that its failure could have bankrupted the production company, but its massive success instead made Cines one of Europe's leading studios

- D.W. Griffith reportedly studied the film's techniques before making 'Intolerance' (1916)

- The original negative was partially destroyed in a fire at the Cines studio in the 1920s, though copies survived in various archives

- The film was one of the first to use moving cameras during action sequences, particularly in the battle scenes

- It was one of the earliest films to receive a theatrical release in the United States, helping establish the market for foreign films in America

- The title 'Quo Vadis?' is Latin for 'Where are you going?' and refers to the biblical story of Peter meeting Jesus on the Appian Way

- The film's success led to a surge of interest in Roman history and early Christianity in popular culture

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics hailed 'Quo Vadis?' as a masterpiece of cinematic art, with particular praise for its ambitious scope and technical achievements. The New York Times called it 'the most remarkable film ever produced' and noted its 'unprecedented grandeur and artistic merit.' French critics compared it favorably to classical art, while German publications praised its historical accuracy and emotional power. Modern critics recognize the film as a landmark achievement, though they note that some elements appear dated by contemporary standards. Film historians consistently rank it among the most important films of the silent era, with particular appreciation for its influence on subsequent cinema. The film's restoration and re-release in recent years has led to renewed critical appreciation for its artistic merits and historical importance. Critics today often emphasize how the film managed to balance spectacle with genuine emotional depth, a combination that would become the hallmark of great epics.

What Audiences Thought

The film was an immediate sensation with audiences worldwide, breaking box office records in virtually every market where it was released. Italian audiences flocked to see it, with many attending multiple times to absorb its visual splendor. The film's religious themes resonated particularly strongly with Catholic audiences across Europe and America, though it also attracted secular viewers drawn to its spectacle. In the United States, it helped establish the market for foreign films, with American audiences proving willing to embrace Italian productions despite language barriers. The film's success led to a surge of interest in Roman history and early Christianity, with many viewers seeking out Sienkiewicz's original novel after seeing the film. Contemporary audience reactions were recorded in numerous newspapers and magazines, with many describing the experience as overwhelming and transformative. The film's popularity endured for years, with revivals continuing to draw audiences well into the 1920s. Modern audiences who have seen restored versions report being impressed by the film's scale and ambition, though some find the pacing challenging by contemporary standards.

Awards & Recognition

- Grand Prize at the 1913 Milan International Exhibition

- Medal of Honor from the Italian Ministry of Education for Cultural Achievement

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Henryk Sienkiewicz's novel 'Quo Vadis' (1896)

- Italian historical paintings of the 19th century

- Grand Opera traditions of Italy

- Earlier Italian historical films like 'The Fall of Troy' (1911)

- Classical Roman literature and historical accounts

This Film Influenced

- Cabiria (1914)

- Intolerance (1916)

- The Ten Commandments (1923)

- Ben-Hur (1925)

- The Sign of the Cross (1932)

- Quo Vadis (1951)

- Ben-Hur (1959)

- The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965)

- Gladiator (2000)

- The Passion of the Christ (2004)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in various versions and archives, though no complete original print exists. The most complete version runs approximately 120 minutes and is held in several archives including the Cineteca Nazionale in Rome and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. A restoration was completed in the 1990s using elements from multiple sources, including a tinted version discovered in the Netherlands. Some scenes remain incomplete or missing, particularly from the fire sequence. The film has been released on DVD and Blu-ray by several specialty labels, often with newly composed scores. The preservation status represents both the challenges and successes of silent film conservation, with the film surviving despite the partial destruction of the original negative in a 1920s studio fire.