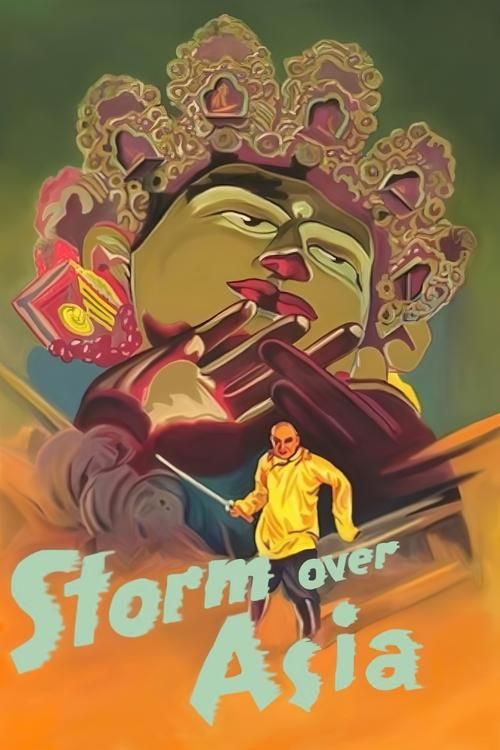

Storm Over Asia

"The Heir of Genghis Khan Rises Against Imperialism"

Plot

In 1918, a young Mongol trapper named Bair is cheated out of a valuable fox fur by a European capitalist trader at a remote trading post. After being ostracized and fleeing to the hills following a violent confrontation with the trader, Bair later becomes a Soviet partisan fighting against the British occupying forces in 1920. During a cattle requisition operation, Bair is shot by British soldiers but discovered to be wearing an amulet suggesting he's a direct descendant of Genghis Khan. The British army, seeing political opportunity, nurses him back to health and installs him as the head of a puppet Mongolian government. However, the once-simple herdsman ultimately rebels against his imperialist manipulators in a furious uprising, embodying the revolutionary spirit against colonial oppression.

About the Production

The film was shot on location in harsh conditions to authentically depict the Mongolian landscape. Director Vsevolod Pudovkin insisted on using real Mongolian actors and extras whenever possible, though lead actor Valéry Inkijinoff was actually of Buryat heritage. The production faced significant challenges including extreme weather conditions, difficulties in transporting equipment to remote locations, and political scrutiny from Soviet authorities regarding the film's revolutionary messaging. The elaborate battle sequences involved hundreds of extras and were choreographed to maximize dramatic impact while conveying the film's anti-imperialist themes.

Historical Background

Storm Over Asia was produced during a crucial period in Soviet history, coinciding with the First Five-Year Plan (1928-1932) and Stalin's consolidation of power. The film reflects the Soviet Union's complex relationship with its Asian republics and neighboring territories, promoting a narrative of anti-imperialist solidarity while justifying Soviet influence in the region. The British forces depicted in the film represent Western imperialism, which was a major theme in Soviet propaganda of the era. The film's production occurred as silent cinema was reaching its artistic peak in the Soviet Union, with directors like Eisenstein, Vertov, and Pudovkin pioneering new cinematic techniques. The historical setting of 1918-1920 was significant, as this period saw the Russian Civil War and foreign intervention in Russia's affairs, making the anti-imperialist themes particularly resonant with contemporary Soviet audiences. The film also coincided with growing Soviet interest in Central Asia, both as a source of resources and as a buffer against potential Western influence.

Why This Film Matters

Storm Over Asia represents a landmark in Soviet cinema and international film history, exemplifying the artistic and political ambitions of early Soviet filmmakers. The film's innovative montage techniques and powerful visual storytelling influenced generations of filmmakers worldwide, particularly in how political themes could be conveyed through cinematic language. Its portrayal of colonial resistance and anti-imperialist struggle made it significant beyond Soviet borders, inspiring filmmakers in newly independent nations and anti-colonial movements. The film challenged Western stereotypes about Asian peoples while simultaneously promoting Soviet ideological positions about international solidarity. Its visual style, particularly the dramatic landscape shots and dynamic action sequences, helped establish a visual vocabulary for epic historical cinema. The film's preservation and continued study in film schools worldwide testifies to its enduring artistic importance, and it remains one of the most accessible examples of Soviet montage theory in practice.

Making Of

Director Vsevolod Pudovkin was deeply influenced by Lev Kuleshov's theories of montage and applied these principles throughout 'Storm Over Asia'. The production was particularly challenging due to the remote filming locations, requiring the crew to transport heavy cameras and equipment across difficult terrain. Pudovkin insisted on authenticity, spending months researching Mongolian customs, costumes, and historical details. The casting process was extensive, with Pudovkin searching for actors who could authentically portray Asian characters without resorting to caricature. Valéry Inkijinoff was discovered after a lengthy search and underwent intensive preparation for the role, including studying Mongolian horse riding techniques and traditional customs. The battle sequences were choreographed with military precision, involving real cavalry charges and explosives that posed significant safety risks to the cast and crew. Pudovkin's innovative use of close-ups and rapid cutting during emotional scenes was groundbreaking for the time and influenced countless future filmmakers.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Storm Over Asia, handled by Anatoly Golovnya, represents some of the most sophisticated visual work of late silent cinema. Golovnya employed dramatic wide shots to capture the vastness of the Mongolian landscape, creating a sense of both isolation and grandeur that mirrors the protagonist's journey. The film features innovative use of low-angle shots to emphasize power dynamics, particularly in scenes depicting British colonial authority. The battle sequences utilize dynamic camera movement and rapid editing to create visceral impact, while intimate moments are captured with expressive close-ups that reveal the characters' internal struggles. The cinematography makes effective use of natural light, particularly in outdoor scenes where the harsh sunlight of the steppe creates dramatic contrasts. The film's visual style evolves with the narrative, beginning with more static, observational shots during the protagonist's simple life and becoming increasingly dynamic as he becomes embroiled in revolutionary struggle. The black and white photography achieves remarkable tonal range, from the blinding whites of snow-covered landscapes to the deep shadows of night scenes, creating a rich visual texture that enhances the film's emotional impact.

Innovations

Storm Over Asia pioneered several technical innovations that influenced cinema worldwide. Pudovkin's sophisticated use of montage, particularly his 'intellectual montage' technique, created meaning through the collision of images rather than through linear narrative alone. The film's action sequences featured groundbreaking camera techniques, including tracking shots mounted on moving vehicles and horses to create dynamic movement during battle scenes. The production utilized multiple cameras simultaneously for complex sequences, allowing for more sophisticated editing possibilities. The film's special effects, particularly the simulated battle sequences and explosions, were remarkably realistic for the time and set new standards for action cinematography. The makeup and prosthetics used to transform actors into different characters, particularly in aging the protagonist, were innovative for the era. The film's preservation of detail in both highlight and shadow areas demonstrated advanced understanding of film exposure techniques. The production also developed new methods for filming in extreme weather conditions, creating custom camera housings and equipment modifications to handle the harsh filming environment. These technical achievements not only served the film's artistic vision but also pushed the boundaries of what was technically possible in cinema at the time.

Music

As a silent film, Storm Over Asia was originally accompanied by live musical performances that varied by theater and location. The score was typically composed to match the film's dramatic arc, with traditional Russian and Central Asian folk melodies incorporated to enhance the cultural authenticity of the setting. Major Soviet theaters employed full orchestras to perform specially commissioned scores, while smaller venues used piano or organ accompaniment. The music emphasized the film's emotional beats, with martial themes for battle sequences, melancholic melodies for moments of oppression, and triumphant fanfares for revolutionary victories. Modern restorations of the film have featured newly composed scores by contemporary musicians, including attempts to recreate the style of 1920s Soviet film music. Some versions have incorporated traditional Mongolian throat singing and instruments to enhance cultural authenticity. The absence of synchronized sound actually enhances the film's universal appeal, as the visual storytelling transcends language barriers, and the musical accompaniment can be adapted to different cultural contexts while maintaining the film's emotional power.

Famous Quotes

I am the descendant of Genghis Khan! I will not be your puppet!

You cheat us because you think we are simple, but our simplicity is our strength.

The land does not belong to those who write papers, but to those who work it.

Your guns are strong, but our spirit is stronger.

When the people rise, even the mightiest empire trembles.

You have awakened a sleeping dragon, and now you will face its fire.

I was a simple herdsman, but you made me a king. Now I will be your undoing.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening fox fur trading sequence where Bair is cheated by the European trader, establishing the film's themes of exploitation and injustice

- The dramatic cavalry charge across the steppe during the battle between Soviet partisans and British forces, featuring hundreds of horsemen and innovative camera work

- The discovery of the Genghis Khan amulet on Bair's body after he's shot, the pivotal moment that changes the course of the narrative

- The elaborate coronation ceremony where Bair is installed as the puppet ruler, contrasting traditional Mongolian rituals with British political manipulation

- The final uprising sequence where Bair turns against his British manipulators, culminating in a powerful montage of revolutionary action and liberation

Did You Know?

- The film's original Russian title is 'Потомок Чингисхана' (Potomok Chingiskhana), meaning 'The Descendant of Genghis Khan'

- Lead actor Valéry Inkijinoff was not actually Mongolian but of Buryat heritage, an ethnic group from Siberia with cultural similarities to Mongols

- The film was part of Pudovkin's revolutionary trilogy, following 'Mother' (1926) and preceding 'The End of St. Petersburg' (1927)

- British soldiers in the film were played by Soviet actors wearing British military uniforms that were meticulously researched for accuracy

- The fox fur that triggers the initial conflict was actually a valuable silver fox pelt, worth a small fortune in 1918

- Pudovkin used over 50,000 feet of film stock to capture the expansive battle sequences and landscape shots

- The amulet worn by the protagonist was designed based on actual Mongolian talismans from the 13th century

- The film was temporarily banned in several Western countries due to its strong anti-imperialist and pro-Soviet messaging

- Many of the Mongolian costumes and props were authentic pieces sourced from museums and private collections

- The film's montage sequences were studied extensively in film schools as examples of revolutionary Soviet editing techniques

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised Storm Over Asia as a masterpiece of revolutionary cinema, with particular acclaim for Pudovkin's directorial vision and the film's powerful political messaging. Pravda and other Soviet publications highlighted the film's contribution to socialist art and its effective critique of imperialism. Western critics were more divided, with some acknowledging the film's technical brilliance while others criticized its overt propaganda elements. French and German film journals of the era particularly praised Pudovkin's innovative editing techniques and visual storytelling. Modern critics have reevaluated the film as a complex work that balances artistic innovation with political messaging, often ranking it among the greatest silent films ever made. The film's reputation has grown over time, with contemporary scholars appreciating both its historical significance and its enduring artistic merits. Film historian Jay Leyda described it as 'one of the most powerful indictments of colonialism ever committed to film,' while modern critics continue to praise its visual sophistication and emotional power.

What Audiences Thought

Storm Over Asia was highly successful with Soviet audiences upon its release, drawing large crowds in major cities and provincial theaters alike. Working-class viewers particularly responded to the film's anti-imperialist themes and the protagonist's transformation from oppressed herdsman to revolutionary leader. The film's action sequences and dramatic story made it accessible to audiences of all educational levels, contributing to its broad appeal. In international markets, the film found appreciative audiences in countries with left-wing political leanings, particularly in France and Germany where it was shown in workers' film clubs. The film's visual power transcended language barriers, making it effective even for audiences who couldn't understand the Russian intertitles. Contemporary audiences at revival screenings continue to respond strongly to the film's emotional intensity and visual spectacle, with many noting how its themes of resistance against oppression remain relevant today. The film has maintained a dedicated following among classic film enthusiasts and is frequently featured in silent film festivals worldwide.

Awards & Recognition

- Honorable Mention at the International Film Exhibition in Venice, 1934

- State Prize of the RSFSR (Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic), 1928

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The Battleship Potemkin (1925) by Sergei Eisenstein - influenced montage techniques

- Strike (1925) by Sergei Eisenstein - influenced political messaging through film

- The General Line (1929) by Dziga Vertov - influenced documentary-style authenticity

- October: Ten Days That Shook the World (1928) by Sergei Eisenstein - influenced historical epic scale

- Kuleshov's montage theory - fundamental influence on editing approach

- Traditional Mongolian epic poetry - influenced narrative structure and themes

This Film Influenced

- Alexander Nevsky (1938) by Sergei Eisenstein - influenced battle sequence choreography

- The Grapes of Wrath (1940) by John Ford - influenced social realist approach

- The Battle of Algiers (1966) by Gillo Pontecorvo - influenced anti-colonial narrative structure

- Lawrence of Arabia (1962) by David Lean - influenced desert epic cinematography

- The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006) by Ken Loach - influenced anti-imperialist themes

- Mongol (2007) by Sergei Bodrov - influenced portrayal of Mongolian culture and history

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Storm Over Asia has been preserved through multiple restoration efforts and is considered to be in good condition for a film of its age. The original negatives were stored at the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow, where they survived World War II and the subsequent Soviet period. A major restoration was undertaken in the 1970s by Soviet film archivists, who created new preservation prints from surviving elements. In the 1990s, further restoration work was done as part of international efforts to preserve classic Soviet cinema. The Criterion Collection released a digitally restored version on Blu-ray in 2010, featuring a new musical score and extensive bonus materials. The film exists in its complete original form, though some versions shown internationally were slightly truncated for various reasons. The preservation status allows modern audiences to experience the film with visual quality approaching its original theatrical presentation.