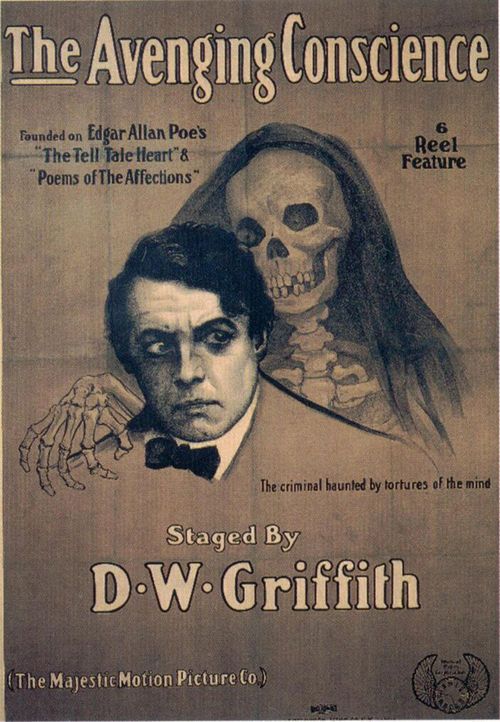

The Avenging Conscience

Plot

A young man, deeply in love with his cousin, finds his romance thwarted by his tyrannical uncle who forbids their relationship. Consumed by dark thoughts influenced by Edgar Allan Poe's writings, the nephew becomes convinced that murder is a natural solution to his problems. He kills his uncle and buries the body beneath the floorboards of their home, but his conscience immediately begins to torment him. As paranoia sets in, he experiences vivid hallucinations and nightmarish visions, including ghostly appearances and the sound of his uncle's beating heart growing louder. The psychological torment becomes unbearable, driving him to the brink of madness as police investigation closes in, ultimately leading to his confession and mental breakdown.

About the Production

This was one of D.W. Griffith's early feature-length experiments, combining elements from two Edgar Allan Poe works: 'The Tell-Tale Heart' and 'Annabel Lee.' The film was notable for its extensive use of symbolic imagery and psychological horror elements, which were innovative for the time. Griffith employed sophisticated double exposure techniques to create the ghostly hallucinations that haunt the protagonist. The production marked one of the first serious attempts at psychological horror in American cinema, moving away from the more common gothic and supernatural horror of the period.

Historical Background

1914 was a pivotal year in world history and cinema. World War I began in Europe, though the United States would not enter until 1917. In the film world, 1914 marked the transition from short films to feature-length pictures as the industry standard. D.W. Griffith was at the forefront of this evolution, having already established himself as America's most innovative director. The film industry was rapidly consolidating in Hollywood, with California becoming the center of American film production. This period saw the emergence of more sophisticated storytelling techniques, moving away from the simple theatrical presentations of earlier cinema. 'The Avenging Conscience' was part of Griffith's experimentation with longer narratives and more complex psychological themes, paving the way for his later masterpieces like 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915) and 'Intolerance' (1916). The film also reflected the growing influence of literature on cinema, with adaptations of classic works becoming increasingly common as filmmakers sought to legitimize the new medium.

Why This Film Matters

'The Avenging Conscience' holds a unique place in cinema history as one of the earliest examples of psychological horror in American film. While European filmmakers had been exploring psychological themes, this film helped establish the genre in the United States, influencing countless later horror films that would focus on internal rather than external threats. The film's adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe's works demonstrated cinema's potential to adapt literary classics in sophisticated ways, treating them as serious art rather than mere entertainment. Its visual innovations, particularly the use of double exposure for hallucination sequences, became standard techniques in horror cinema. The film also represents an important step in the development of feature-length narrative films, helping establish the format that would dominate cinema for the next century. Griffith's exploration of guilt and conscience as dramatic themes influenced later film noir and psychological thriller genres. The movie's commercial and critical success helped prove that audiences were ready for more complex, psychologically sophisticated storytelling in films.

Making Of

The production of 'The Avenging Conscience' represented a significant artistic leap for D.W. Griffith as he moved from the short films that dominated the era to more complex feature-length storytelling. Griffith was deeply influenced by European art films and sought to elevate American cinema beyond simple melodramas. The film's psychological horror elements required innovative visual techniques, including sophisticated use of double exposure to create the ghostly visions that haunt the protagonist. Griffith worked closely with cinematographer Billy Bitzer to develop these effects, pushing the technical boundaries of what was possible in 1914. The casting of Henry B. Walthall was particularly inspired, as his expressive face could convey the mounting psychological torment without dialogue. The production faced challenges from studio executives who were concerned that the dark subject matter might alienate audiences, but Griffith persisted, believing in the artistic merit of exploring psychological themes. The film's score, though not recorded, was carefully planned with detailed musical cues for live accompaniment during screenings, including specific instructions for the famous beating heart sequence.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Billy Bitzer was groundbreaking for its time, featuring innovative techniques that would influence cinema for decades. Bitzer employed sophisticated double exposure methods to create the ghostly hallucinations that haunt the protagonist, a technique that was still experimental in 1914. The film uses dramatic lighting contrasts to emphasize the psychological states of the characters, with deep shadows representing the protagonist's descent into madness. Camera movement was more dynamic than typical of the period, with Bitzer using subtle tracking shots to follow characters through their psychological journey. The burial scene beneath the floorboards featured innovative low-angle shots that created a sense of claustrophobia and guilt. Bitzer also experimented with focus changes to represent shifts in consciousness, blurring and sharpening the image to reflect the protagonist's mental state. The film's visual style influenced the later German Expressionist movement with its emphasis on psychological states through visual means. The cinematography helped establish many visual conventions that would become standard in psychological horror films.

Innovations

The film featured several technical innovations that were ahead of their time. The double exposure techniques used to create the ghostly visions were particularly sophisticated, requiring precise timing and multiple exposures on the same film strip. Griffith and his team developed new methods for creating convincing hallucination sequences that would influence visual effects in cinema for decades. The film's editing was more complex than typical of the period, using cross-cutting between reality and hallucination to represent the protagonist's psychological state. The production also experimented with camera angles and movement to create psychological impact, including unusual low angles for the burial scene. The film's pacing was innovative, building tension gradually through visual means rather than relying on intertitles. Special effects were used to create supernatural elements, including floating objects and ghostly apparitions. The production design was carefully planned to reflect the psychological themes, with sets becoming increasingly distorted as the protagonist's madness progresses. These technical achievements helped establish new possibilities for psychological storytelling in cinema.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Avenging Conscience' was originally accompanied by live musical performance during screenings. Griffith provided detailed musical cues in the film's documentation, specifying particular pieces for different scenes to enhance the psychological impact. The most famous musical element was the use of increasingly loud percussion to represent the beating heart that haunts the protagonist, a technique that required skilled musicians to execute effectively. Many theaters used classical pieces, particularly works by composers known for their dramatic intensity, such as Wagner and Liszt. Some larger theaters commissioned original scores from resident composers. The musical accompaniment was crucial to the film's horror elements, with sudden changes in tempo and volume used to create jump scares and psychological tension. Modern restorations have been scored by contemporary composers who attempt to recreate the intended emotional impact while using modern musical resources. The original musical approach demonstrated how early filmmakers used sound to enhance psychological horror, a tradition that would continue into the sound era.

Famous Quotes

(Intertitle) 'The conscience of man is a terrible thing when it is awakened.'

(Intertitle) 'In his madness, he saw visions that would have driven a sane man to despair.'

(Intertitle) 'The beating of his heart grew louder, louder, LOUDER!'

(Intertitle) 'Murder? Is it not merely a part of the great scheme of nature?'

(Intertitle) 'Love denied becomes a poison in the soul.'

Memorable Scenes

- The murder sequence where the nephew kills his uncle, shot with dramatic shadows and minimal violence but maximum psychological impact

- The burial beneath the floorboards scene, using innovative camera angles to create claustrophobia and guilt

- The hallucination sequences featuring ghostly apparitions created through double exposure techniques

- The famous beating heart scene where the protagonist hears increasingly loud heartbeats driving him to madness

- The final confession scene where the psychological torment becomes unbearable and the protagonist breaks down completely

Did You Know?

- The film is an adaptation of two Edgar Allan Poe works: 'The Tell-Tale Heart' provides the murder and guilt elements, while 'Annabel Lee' supplies the romantic subplot

- This was one of the first American films to explore psychological horror rather than relying on supernatural elements

- D.W. Griffith considered this film one of his most experimental works in terms of visual storytelling techniques

- The beating heart sound effect was created by having a percussionist drum increasingly louder during screenings

- Henry B. Walthall, who plays the nephew, had previously starred in Griffith's 'The Birth of a Nation' the following year

- The film's original title was simply 'The Conscience' but was changed to 'The Avenging Conscience' to emphasize the horror elements

- Blanche Sweet, who plays the cousin, was one of Griffith's favorite actresses and appeared in over 20 of his films

- The film was shot during the same period when Griffith was planning his epic 'Intolerance,' showing his range from intimate psychological drama to massive historical spectacle

- The burial scene beneath the floorboards was achieved using clever camera angles and set construction rather than actual digging

- Contemporary audiences found the psychological intensity of the film disturbing, with some critics calling it 'too intense for polite society'

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film's artistic ambitions and technical innovations. The New York Dramatic Mirror called it 'a masterpiece of psychological drama' and noted Griffith's 'remarkable ability to visualize mental states.' Variety praised the performances, particularly Henry B. Walthall's portrayal of mounting madness. Some critics, however, found the film's intensity disturbing, with The Moving Picture World suggesting it was 'perhaps too morbid for general audiences.' Modern critics have reevaluated the film as an important precursor to psychological horror cinema. Film historian Kevin Brownlow has called it 'remarkably ahead of its time in its exploration of guilt and madness.' The film is now recognized as a significant step in Griffith's artistic development and an important early example of American horror cinema. Many contemporary scholars note how the film's visual techniques and psychological depth influenced later generations of horror filmmakers, from German Expressionism to modern psychological thrillers.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reactions to 'The Avenging Conscience' were mixed but generally positive, with many viewers impressed by the film's psychological intensity and visual innovations. The film performed well in major urban markets where audiences were more accustomed to sophisticated entertainment. Some viewers found the subject matter disturbing, particularly the murder and subsequent psychological torment, which was unusual for the period. The film's success helped demonstrate that audiences were ready for more complex, adult themes in motion pictures. In smaller towns and more conservative markets, the film sometimes faced resistance from local censors who objected to its dark themes. Despite these challenges, the film developed a reputation as a 'thinking person's picture' and attracted audiences interested in more artistic cinema. Over time, it gained a cult following among early cinema enthusiasts who appreciated its psychological depth and technical achievements. Modern audiences viewing restored versions often express surprise at how sophisticated and psychologically complex a 1914 film could be.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Edgar Allan Poe's 'The Tell-Tale Heart'

- Edgar Allan Poe's 'Annabel Lee'

- German Expressionist cinema (though this film predated most Expressionist works)

- Contemporary stage melodramas

- Psychological literature of the early 20th century

- Griffith's own earlier Biograph shorts

This Film Influenced

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- Nosferatu (1922)

- The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

- Psycho (1960)

- The Shining (1980)

- The Tell-Tale Heart adaptations

- Various film noir psychological thrillers

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film survives in complete form and has been preserved by major film archives including the Museum of Modern Art and the Library of Congress. A restored version was released in the early 2000s with improved image quality and a new musical score. The original nitrate elements have been transferred to safety film and digital formats for long-term preservation. Some scenes show signs of deterioration typical of films from this era, but the overall print quality is remarkably good considering its age. The film is considered one of the better-preserved examples of Griffith's early feature work.