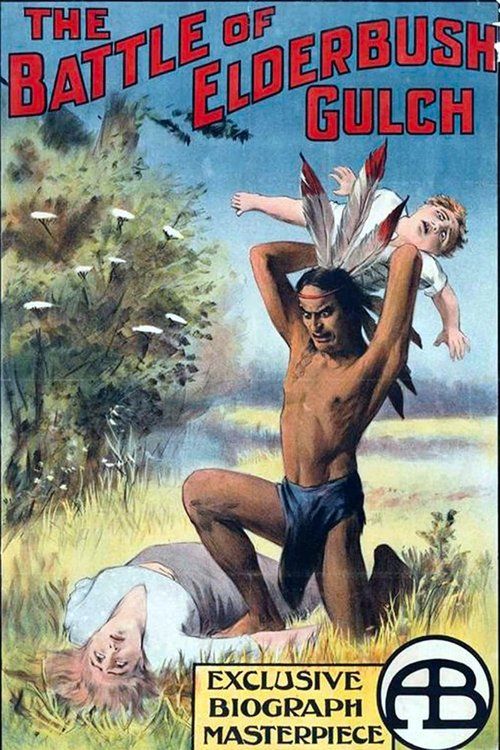

The Battle at Elderbush Gulch

"A Thrilling Drama of Western Life"

Plot

Two young sisters are sent by their mother to live with their uncle in the remote Western town of Elderbush Gulch. The girls bring along their beloved pets - a dog and a kitten - but their stern uncle forbids animals in his home. When the pets escape and cause chaos in the town, the girls run away in fear of punishment. They wander into the wilderness where they are captured by a Native American tribe who mistake them for enemies. Meanwhile, the townspeople discover the girls are missing and organize a rescue party, leading to a dramatic battle between the cavalry and the Native Americans at Elderbush Gulch. The film culminates in a thrilling rescue sequence where the girls are saved just in time, reuniting with their relieved family and townsfolk.

About the Production

This was one of hundreds of short films D.W. Griffith directed for Biograph between 1908-1913. The film was shot quickly, often in just a few days, which was standard practice for Biograph productions. Griffith was already experimenting with narrative techniques that would later define his feature films, including cross-cutting between parallel actions to build tension. The battle scenes were filmed using actual Native American extras who were frequently employed by Hollywood studios during this period.

Historical Background

1913 was a transformative year in American cinema, occurring during the transition from short films to feature-length productions. The film industry was rapidly consolidating, with studios like Biograph competing for audiences in increasingly luxurious movie palaces. This period saw the rise of the star system, with actors like Mae Marsh becoming recognizable draws for audiences. The American West was still relatively fresh in public memory, making Western films extremely popular. The film was released just before World War I would reshape global politics and cinema. Technologically, 1913 was a year of innovation in film equipment, with better cameras and film stocks becoming available. The motion picture industry was also fighting legal battles, particularly with Thomas Edison's Motion Picture Patents Company, which controlled many film technologies. Griffith himself was becoming increasingly frustrated with the limitations of short films and would soon revolutionize cinema with his feature-length epics.

Why This Film Matters

'The Battle at Elderbush Gulch' represents an important milestone in the development of American cinema, particularly in the Western genre and the evolution of film language. The film demonstrates D.W. Griffith's mastery of narrative storytelling and his pioneering use of cinematic techniques like cross-cutting, which would become fundamental to film grammar. While the film reflects the racial stereotypes and colonial attitudes of its time, particularly in its portrayal of Native Americans, it also shows how cinema was shaping American cultural myths about the West. The film's emphasis on family values and the protection of innocent children resonated with Progressive Era audiences concerned with social issues. As part of Griffith's body of work, it contributed to establishing the United States as a dominant force in global cinema. The film also exemplifies the transition from the novelty phase of cinema to its emergence as a serious artistic medium capable of complex emotional storytelling.

Making Of

The production of 'The Battle at Elderbush Gulch' took place during a pivotal moment in cinema history when D.W. Griffith was transforming filmmaking from simple recorded stage plays into a sophisticated narrative art form. Griffith was known for his demanding directing style and attention to detail. He would often rehearse scenes extensively and was one of the first directors to move his camera away from static positions to create more dynamic shots. The battle sequences were particularly challenging to coordinate, requiring careful timing of explosions, horse stunts, and actor movements. Griffith's collaboration with cinematographer Billy Bitzer was crucial in achieving the film's visual impact. The cast, particularly Mae Marsh, was trained in Griffith's method of naturalistic acting, which was revolutionary compared to the exaggerated theatrical style common in early cinema. The film was processed and printed at Biograph's facilities in New York, with Griffith often personally supervising the final editing to ensure his vision was preserved.

Visual Style

The cinematography in 'The Battle at Elderbush Gulch' was handled by Billy Bitzer, D.W. Griffith's longtime collaborator and one of the most innovative cinematographers of the early cinema era. The film showcases Bitzer's mastery of various camera techniques that were revolutionary for their time, including dynamic camera movements and strategic use of close-ups to emphasize emotional moments. The battle sequences demonstrate sophisticated use of wide shots to establish the scale of the action, combined with medium shots to follow the key dramatic developments. Bitzer employed natural lighting for the outdoor scenes, creating authentic Western atmosphere while maintaining the necessary exposure for the film stock of the period. The film also features early examples of what would become known as parallel editing, with Bitzer and Griffith using camera angles and composition to create visual continuity between different narrative threads. The cinematography successfully balances intimate character moments with spectacular action, helping to establish the visual language that would define American cinema.

Innovations

'The Battle at Elderbush Gulch' showcased several technical innovations that were advancing the art of cinema in 1913. The film's most significant achievement was its sophisticated use of cross-cutting between parallel actions, a technique that Griffith was perfecting during this period. This editing approach created suspense and dramatic irony by showing multiple events occurring simultaneously. The battle sequences demonstrated advanced coordination of multiple camera setups and complex action staging, requiring precise timing of explosions, horse stunts, and actor movements. The film also utilized varying shot distances, from long shots establishing the Western landscape to close-ups capturing emotional reactions, helping to develop the visual vocabulary of cinema. The production employed location shooting in natural settings, which was becoming increasingly common as cameras became more portable. The film's special effects, particularly during the battle scenes, used practical techniques like controlled explosions and stunt work that pushed the boundaries of what was technically possible in early cinema.

Music

As a silent film, 'The Battle at Elderbush Gulch' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The typical accompaniment would have consisted of a pianist or small orchestra in larger theaters, playing a combination of classical pieces, popular songs, and specially composed cues. The music would have been synchronized with the on-screen action, with dramatic themes during the battle scenes, tender melodies for the family moments, and suspenseful motifs during the girls' capture. Theater music directors would have used cue sheets provided by Biograph, which suggested appropriate musical selections for different scenes. The score would have emphasized the emotional content of each scene, using leitmotifs for different characters and situations. During the battle sequence, the music would have become increasingly frantic and percussive, perhaps using drums and brass instruments to simulate the sounds of conflict. The musical accompaniment was crucial to the audience's experience, providing emotional guidance and narrative clarity that couldn't be conveyed through dialogue.

Famous Quotes

As a silent film, dialogue was conveyed through intertitles. Key intertitles included: 'The little girls were sent to live with their uncle', 'The Indians attack the town!', 'The cavalry rides to the rescue!', 'The children are saved!'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the emotional farewell between mother and children as the girls depart for their uncle's home

- The chaotic scene where the pets escape and cause disruption in the town, leading to the girls' decision to run away

- The tense capture sequence as the girls are discovered by Native Americans in the wilderness

- The spectacular battle sequence where the cavalry arrives to save the town, featuring coordinated horse stunts, explosions, and large-scale action

- The emotional reunion scene where the girls are safely returned to their family and the grateful townspeople celebrate their rescue

Did You Know?

- This film was part of D.W. Griffith's prolific period where he directed over 450 short films for Biograph Company

- Mae Marsh, who starred in the film, became one of Griffith's favorite actresses and later appeared in his controversial masterpiece 'The Birth of a Nation' (1915)

- The film demonstrates Griffith's pioneering use of cross-cutting to build suspense during the climactic battle sequence

- Robert Harron, who appears in this film, was another Griffith regular who tragically died at age 27 in 1920

- The Native American characters were played by actual Native American actors, which was somewhat progressive for the time, though they were still portrayed through stereotypical lens

- The film's title 'Elderbush Gulch' was likely fictional, created specifically for this production

- This was one of the last films Griffith made for Biograph before moving to Reliance-Majestic Studios to make feature films

- The battle sequence required extensive coordination of extras, horses, and props, showcasing Griffith's growing expertise in directing large-scale action scenes

- The film's themes of family separation and reunion were recurring motifs in Griffith's work

- Like many films of this era, it was likely shot on 35mm film at approximately 16 frames per second

What Critics Said

Contemporary reviews of 'The Battle at Elderbush Gulch' were generally positive, with critics praising its exciting action sequences and emotional storytelling. The trade publication The Moving Picture World noted the film's 'thrilling battle scenes' and 'excellent performances by the entire cast.' Critics particularly highlighted Mae Marsh's performance as one of the young girls, describing it as 'natural and touching.' The film's technical aspects, especially the coordination of the battle sequence, were frequently mentioned in reviews as evidence of cinema's growing sophistication. Modern critics and film historians view the film as an important example of Griffith's developing style and his contribution to the Western genre. While acknowledging the film's historical significance, contemporary scholars also critically examine its problematic racial representations and its role in perpetuating harmful stereotypes about Native Americans. The film is often studied in film history courses as an example of early narrative cinema and Griffith's influence on film language.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1913 responded enthusiastically to 'The Battle at Elderbush Gulch,' which was typical of the popular Western genre. The film's combination of family drama, adventure, and spectacular action sequences appealed to the diverse audiences attending nickelodeons and increasingly elaborate movie theaters. The emotional story of endangered children created strong audience engagement, while the battle scenes provided the visual spectacle that early cinema audiences craved. The film's success contributed to the growing popularity of its stars, particularly Mae Marsh, who would become one of the most recognized actresses of the 1910s. Audience reactions were often recorded in theater reports sent back to Biograph, which indicated strong attendance and positive word-of-mouth for this title. The film's themes of family protection and frontier justice resonated with American audiences during a period of rapid social change and immigration, offering a comforting vision of traditional values and heroic action.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Biograph Western shorts directed by Griffith

- Contemporary Western literature and dime novels

- Stage melodramas of the late 19th century

- Photographic traditions of the American West

- Buffalo Bill's Wild West Shows

- Thomas Edison's early Western films

- French narrative films of the 1900s

- Italian historical epics

This Film Influenced

- The Birth of a Nation (1915) - Griffith's later feature with similar battle sequences

- Intolerance (1916) - Griffith's cross-cutting techniques refined

- The Covered Wagon (1923) - Epic Western storytelling

- Stagecoach (1939) - Western genre conventions

- The Searchers (1956) - Rescue narrative structure

- Unforgiven (1992) - Western genre deconstruction

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress collection and has been restored by various film archives. A 35mm print exists and has been digitized for preservation purposes. The film is considered relatively complete for its era, though some minor deterioration may be present due to the age of the original nitrate film stock. The restoration work has helped maintain the film's historical significance as an example of early American cinema and D.W. Griffith's developing directorial style.