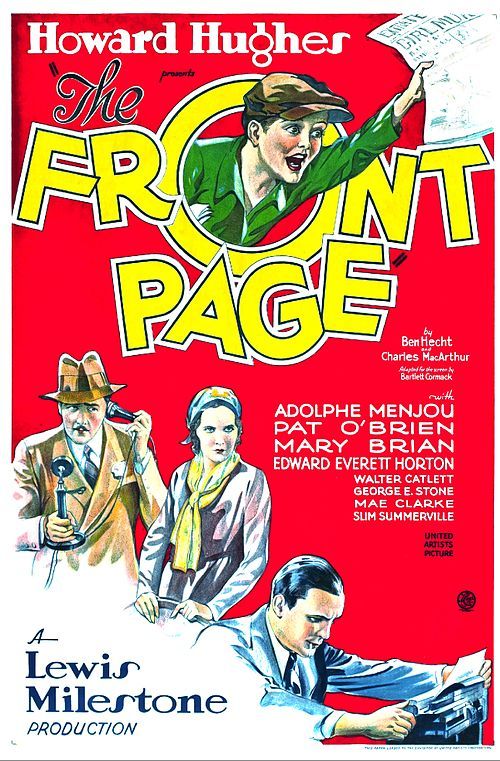

The Front Page

Plot

Hildy Johnson, the star reporter for the Chicago Examiner, is determined to quit journalism to marry his fiancée and lead a respectable life. His scheming editor, Walter Burns, desperately tries to keep him on the paper by offering increasingly larger sums of money and more exciting stories. When condemned murderer Earl Williams escapes from the courthouse during a last-minute reprieve, Hildy finds himself drawn back into the world of sensational journalism. After discovering Williams hiding in the press room, Hildy learns the man may be innocent and becomes embroiled in a conspiracy involving corrupt politicians. Together with Walter, Hildy must hide the prisoner, uncover the truth, and write the scoop of his career while evading the police and his own marriage plans.

About the Production

The film was one of the first to successfully incorporate rapid-fire overlapping dialogue in early sound cinema, requiring innovative recording techniques. The production faced significant challenges with early sound equipment, as the microphone placement had to accommodate the actors' fast-paced movements and multiple speakers in single scenes. Howard Hughes, though uncredited as director, was heavily involved in the production decisions and pushed for the film's controversial content. The entire film was shot in sequence to maintain the complex timing of dialogue scenes, a rare practice even today.

Historical Background

The Front Page emerged during the Great Depression, a time when public trust in institutions was at an all-time low. The film's cynical portrayal of corrupt politicians and sensationalist journalism resonated deeply with audiences grappling with economic hardship and political disillusionment. Chicago in the early 1930s was notorious for its political corruption and organized crime, making the film's setting particularly relevant. The movie was released just as sound technology was becoming standardized in Hollywood, representing a transitional moment in cinema history. The rapid-fire dialogue style reflected the fast pace of modern urban life and the growing cynicism of the era. The film's unflinching look at media manipulation and political corruption was groundbreaking for its time, presaging the investigative journalism movements of later decades.

Why This Film Matters

'The Front Page' established a template for the newspaper comedy genre that would influence countless films. Its rapid-fire dialogue style revolutionized screen comedy and became a hallmark of the screwball genre that followed. The film's cynical yet comedic take on serious subjects like capital punishment and political corruption pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable in mainstream cinema. It helped create the archetype of the hard-boiled, cynical journalist that would appear in numerous subsequent films. The movie's success proved that audiences were ready for more sophisticated, fast-paced comedies that didn't shy away from social commentary. Its influence can be seen in everything from 'His Girl Friday' to modern workplace comedies. The film also helped establish the reputation of its source material as one of the greatest American plays, ensuring multiple future adaptations.

Making Of

The making of 'The Front Page' was marked by technical innovation and creative challenges. As one of the early sound films, it pushed the boundaries of what was possible with audio recording technology. The production team had to develop new methods for capturing the rapid-fire dialogue that was central to the story. Microphones had to be hidden in creative ways to allow actors to move freely while maintaining sound quality. Howard Hughes, though not officially credited as director, was intimately involved in every aspect of production, often making decisions about scenes and dialogue delivery. The film was shot in just a few weeks, a remarkably short time considering its complexity. The cast had to rehearse extensively to perfect the timing of their dialogue, as early sound recording didn't allow for the flexibility of post-production editing. The newsroom set was designed to be as authentic as possible, based on the actual Chicago newsrooms where Hecht and MacArthur had worked.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Edward Cronjager was innovative for its time, employing fluid camera movements that followed the actors through the bustling newsroom set. The film used long takes to capture the rapid dialogue exchanges, requiring precise choreography between actors and camera. The lighting design created a realistic, gritty atmosphere that reflected the newspaper world's chaotic nature. The camera work was more dynamic than most early sound films, which were often static due to technical limitations. The film's visual style helped establish the fast-paced, energetic tone that would become characteristic of the newspaper comedy genre.

Innovations

The film's most significant technical achievement was its successful recording of overlapping dialogue, which was extremely difficult with early sound equipment. The production team developed new microphone placement techniques that allowed actors to move more freely while maintaining sound quality. The film's editing was innovative for its time, using quick cuts to enhance the pace of the dialogue scenes. The movie demonstrated that sound films could maintain the visual dynamism of silent cinema while adding the dimension of realistic audio. These technical innovations influenced countless subsequent films, particularly in the comedy genre.

Music

The film's soundtrack was groundbreaking for its use of diegetic sound and naturalistic audio design. The score by John Leipold was minimal, allowing the dialogue and ambient newsroom sounds to dominate. The film made innovative use of sound effects, including typewriters, telephones, and police sirens, to create a realistic urban atmosphere. The recording techniques developed for this film helped advance the possibilities of sound cinema, particularly in capturing multiple speakers and overlapping dialogue. The sound design emphasized the chaotic energy of the newsroom, using audio to enhance the film's frantic pace.

Famous Quotes

Hildy: 'I'm getting married in the morning and I'm going to be a decent human being from now on.' Walter: 'You'll be back.'

Walter: 'I know. The mother's the one who's got to get up in the morning and lick the stamps.'

Walter: 'A journalist's a journalist. There's no such thing as an ex-journalist.'

Hildy: 'I've been a reporter for eight years. I want to go somewhere where they don't spell 'love' with a double 'o'.'

Walter: 'You're a newspaperman, Hildy. You're born to it.'

Memorable Scenes

- The chaotic opening scene in the press room where reporters frantically type and shout while waiting for news of the execution

- The scene where Hildy discovers Earl Williams hiding in a rolltop desk in the press room

- The frantic sequence where Hildy and Walter try to hide Williams from the police while pretending to conduct interviews

- The climactic scene where the truth about Williams' innocence is revealed through the reporters' investigation

- The final confrontation between Hildy and Walter where Hildy must choose between his marriage and his career

Did You Know?

- Based on the 1928 Broadway play by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, who were both former Chicago reporters

- The original Broadway production ran for 277 performances and was banned in Chicago for its portrayal of corrupt city officials

- This was the first film adaptation of the play, which would be remade multiple times, most famously as 'His Girl Friday' (1940)

- The character of Walter Burns was based on real Chicago editor Walter Howey, who mentored Hecht and MacArthur

- Howard Hughes produced the film through his production company but was uncredited as director

- The film was one of the first to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture (then called 'Outstanding Production')

- The rapid-fire dialogue delivery was revolutionary for early sound films and influenced countless future comedies

- The film was considered quite risqué for its time due to its cynical view of politics and journalism

- Early sound recording technology made the overlapping dialogue scenes extremely difficult to capture

- The play's authors, Hecht and MacArthur, wrote the screenplay adaptation themselves

- The film's success helped establish the screwball comedy genre, though it predated the classic era of the 1930s

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'The Front Page' for its energy, wit, and innovative use of sound. The New York Times called it 'a picture of tremendous vitality and pace,' while Variety noted its 'machine-gun dialogue' as a major innovation. Critics particularly admired the performances of O'Brien and Menjou, who captured the perfect balance of comedy and drama. Modern critics recognize the film as a groundbreaking achievement in early sound cinema, with many considering it superior to some of the more famous remakes. The film is often cited as a precursor to the screwball comedy genre, with its fast pace and cynical wit. Some contemporary critics found the film's pace too frantic and its themes too cynical, but most acknowledged its technical achievements and entertainment value.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1931 were electrified by the film's pace and humor, making it a commercial success despite the economic hardships of the Depression era. Moviegoers were particularly impressed by the natural-sounding dialogue, which was a stark contrast to the stilted delivery common in many early sound films. The film's cynical take on politics and journalism resonated with a public disillusioned by the economic crisis and political scandals of the time. The chemistry between O'Brien and Menjou was widely praised by audiences, who found their rapid exchanges both hilarious and thrilling. The film's success at the box office helped prove that sophisticated, dialogue-driven comedies could be commercially viable, paving the way for the screwball comedies of the mid-1930s.

Awards & Recognition

- National Board of Review Award for Best Film (1931)

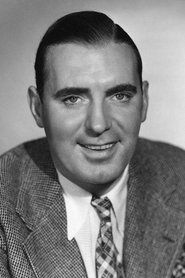

- National Board of Review Award for Best Actor (Adolphe Menjou, 1931)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- The hard-boiled fiction of the 1920s

- Real Chicago journalism of the 1920s

- German Expressionist cinema (for its dynamic camera work)

- Stage comedy traditions

- The cynical worldview of post-WWI literature

This Film Influenced

- His Girl Friday (1940)

- The Front Page (1974)

- Switching Channels (1988)

- All the President's Men (1976)

- Network (1976)

- The Paper (1994)

- Broadcast News (1987)

- Good Night, and Good Luck (2005)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film has been preserved by the Library of Congress and was selected for the National Film Registry in 2010 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. A restored version is available through various film archives and classic film distributors.