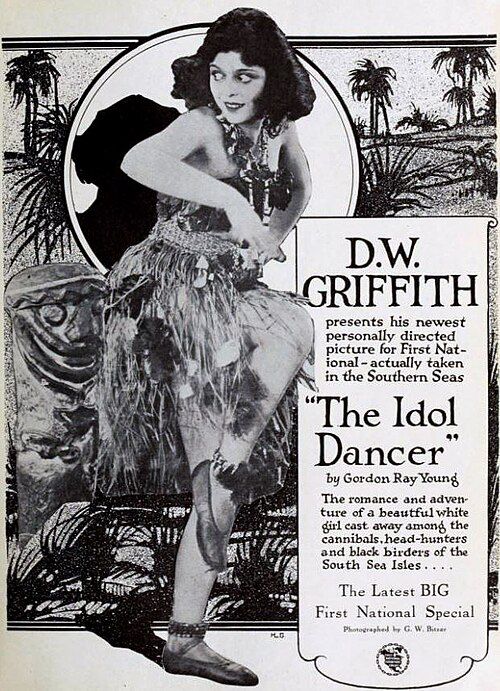

The Idol Dancer

"A Tale of the South Seas Where Civilization Meets Savagery"

Plot

The Idol Dancer follows the story of a religious zealot, his nephew, and an alcoholic beachcomber who find themselves stranded on a remote South Seas island. There they encounter a beautiful native dancer who becomes the center of a cultural and moral conflict. The religious man attempts to 'civilize' the natives and convert them to Christianity, while the beachcomber embraces their way of life. As tensions rise between the Westerners and the islanders, a complex web of desire, manipulation, and cultural misunderstanding unfolds. The film explores themes of colonialism, cultural clash, and the hypocrisy of so-called civilized society when confronted with different value systems.

About the Production

The film was part of Griffith's series of 'South Seas' melodramas, filmed on location to add authenticity. The production faced challenges with tropical weather conditions and the difficulty of filming on remote islands. Griffith employed local indigenous people as extras and consultants to lend credibility to the native scenes. The film was one of the last productions starring Clarine Seymour before her tragic death in 1920.

Historical Background

The Idol Dancer was produced during a transitional period in American cinema and society. The year 1920 marked the beginning of the Jazz Age and the height of the first Red Scare, while also seeing the ratification of the 19th Amendment granting women's suffrage. In cinema, this was the era when feature films were becoming the industry standard, and directors like Griffith were pushing the boundaries of what could be shown on screen. The film's colonial themes reflected America's growing imperial ambitions and the prevailing attitudes of white superiority that dominated Western thought. The early 1920s also saw the beginning of Hollywood's dominance in global cinema, with American films being exported worldwide. The film's exploration of cultural clash and missionary work resonated with contemporary American attitudes toward foreign cultures and the 'civilizing mission' that many believed was their destiny.

Why This Film Matters

The Idol Dancer represents an important, if problematic, example of early Hollywood's engagement with themes of cultural difference and colonialism. The film contributed to the popularization of the 'South Seas' genre that would flourish throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Its portrayal of native cultures, while stereotypical by modern standards, was relatively nuanced for its time, attempting to show both the beauty and complexity of indigenous societies. The film's exploration of religious hypocrisy and the moral ambiguity of 'civilization' versus 'savagery' reflected growing American skepticism about missionary work and colonial enterprises. However, like many films of its era, it also reinforced harmful racial stereotypes and presented a Eurocentric worldview. The film serves today as an important artifact for understanding early 20th-century American attitudes toward race, religion, and cultural difference.

Making Of

The production of The Idol Dancer was part of D.W. Griffith's ambitious series of films exploring different cultures and settings. Griffith invested significant resources in creating authentic-looking native villages and costumes, though many elements were based on Western stereotypes rather than accurate cultural representations. The filming on location in Florida's tropical climate proved challenging for the cast and crew, who had to contend with heat, humidity, and insects. Richard Barthelmess, who had become a star after Griffith's 'Broken Blossoms,' was given significant creative input into his character development. The film's production coincided with Griffith's establishment of his own studio and his attempts to maintain artistic independence from major studios. Tragically, during post-production, star Clarine Seymour fell ill and passed away, casting a pall over the film's release and marketing.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Idol Dancer was handled by G.W. Bitzer, Griffith's longtime collaborator. The film featured innovative location photography that captured the beauty of tropical settings, using natural light to create atmospheric effects. Bitzer employed techniques such as soft focus and backlighting to enhance the romantic and exotic elements of the story. The native dance sequences were particularly notable for their dynamic camera work and use of movement. The film's visual style combined Griffith's characteristic use of cross-cutting and close-ups with the emerging aesthetic of location-based realism. The contrast between the 'civilized' Western characters and the 'savage' islanders was emphasized through lighting and composition, with the island scenes often shot in warmer tones and more fluid camera movements.

Innovations

The Idol Dancer demonstrated several technical innovations for its time, particularly in location photography. The film's production in tropical locations required portable equipment and innovative solutions for lighting in outdoor settings. Griffith's team developed new methods for filming in bright sunlight, using reflectors and filters to control exposure. The film also featured elaborate set constructions that blended seamlessly with natural locations, creating a convincing illusion of a remote South Seas island. The native dance sequences utilized multiple camera setups and dynamic movement, pushing the boundaries of what was technically possible in 1920. The film's special effects, while modest by modern standards, included matte paintings and composite shots that enhanced the exotic atmosphere.

Music

As a silent film, The Idol Dancer would have been accompanied by live musical performance during its theatrical run. The original score was likely composed by Griffith's regular collaborator, Joseph Carl Breil, who had scored 'The Birth of a Nation' and 'Intolerance.' The music would have featured themes representing both Western civilization and native culture, using contrasting musical motifs to underscore the film's central conflict. Typical theater orchestras of the period would have included strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion, with exotic instruments like gongs and rattles used for the native scenes. The score would have incorporated popular songs of the era as well as classical adaptations, following the common practice of silent film accompaniment.

Famous Quotes

Sometimes the savage is more civilized than the man who calls himself so.

In trying to save their souls, we may lose our own.

The devil wears many faces, and some of them are quite respectable.

Memorable Scenes

- The native ritual dance sequence where the islanders perform their traditional ceremony, contrasted with the Westerners' shocked reactions

- The climactic confrontation between the religious zealot and the beachcomber over the dancer's soul

- The storm sequence that strands the Western characters on the island, filmed with innovative special effects

Did You Know?

- This was one of D.W. Griffith's less successful films commercially, contributing to his financial difficulties in the early 1920s

- Clarine Seymour died tragically shortly after this film's release from pneumonia following surgery, making this one of her final screen appearances

- The film was shot on location in Florida and California to simulate the South Seas setting, a relatively uncommon practice for the time

- Richard Barthelmess was reportedly uncomfortable with some of the film's racial stereotypes and colonial themes

- The original title was 'The Idol Dancer of the South Seas' but was shortened for marketing purposes

- The film featured elaborate native costumes and rituals that were researched by Griffith's production team

- This was one of the first films to explore the 'noble savage' trope in depth, contrasting 'civilized' Westerners with 'primitive' islanders

- The beachcomber character was based on real-life expatriates who lived on Pacific islands during the colonial era

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception to The Idol Dancer was mixed to negative. Many critics found the film's themes heavy-handed and its moralizing preachy, even for Griffith's standards. The New York Times criticized the film's melodramatic elements while acknowledging its visual beauty. Variety noted that the film lacked the emotional power of Griffith's earlier works like 'The Birth of a Nation' or 'Intolerance.' Modern critics and film historians generally view the film as a lesser work in Griffith's canon, though some appreciate its visual style and its attempt to address complex themes of cultural conflict. The film is often cited as an example of Griffith's declining artistic power in the 1920s and his struggle to adapt to changing audience tastes.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception to The Idol Dancer was disappointing, contributing to its status as a commercial failure. The film failed to generate the excitement and box office returns that Griffith's earlier works had enjoyed. Contemporary audiences found the story slow-moving and the moralizing tone off-putting. The film's themes of religious hypocrisy and cultural clash did not resonate with post-World War I audiences who were seeking more escapist entertainment. The tragic death of Clarine Seymour shortly before the film's release may have also affected audience interest, as she was an emerging star with a growing following. The film's poor performance was part of a pattern of commercial disappointments that would eventually lead Griffith to seek financing from major studios rather than maintaining his independence.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Robert Louis Stevenson's South Sea Tales

- Joseph Conrad's colonial literature

- Eden and paradise myths

- Missionary literature of the 19th century

- Travelogues and ethnographic films

This Film Influenced

- Moana (1926)

- Tabu (1931)

- Bird of Paradise (1932)

- Hurricane (1937)

- White Cargo (1942)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Idol Dancer is considered a lost film. No complete copies are known to survive in any film archive or private collection. Only fragments and still photographs from the production remain, preserved at the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. The film's loss is particularly significant as it represents one of Clarine Seymour's final performances and an important example of Griffith's 1920s work. Some production stills and continuity scripts survive, providing partial documentation of the film's content. The film's status as lost is typical of Griffith's work from this period, many of which have not survived due to the unstable nature of early film stock and inadequate preservation efforts in the early decades of cinema.