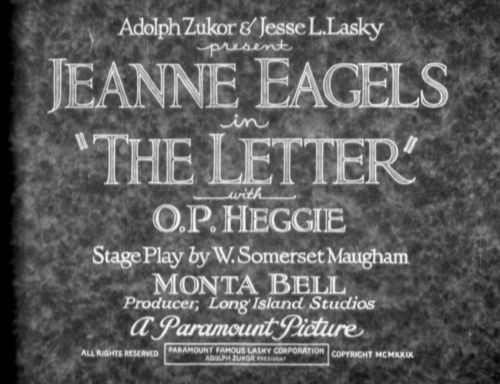

The Letter

"A Woman's Love... A Woman's Crime... A Woman's Fate!"

Plot

Set in British Malaya, Leslie Crosbie, the wife of a rubber plantation owner, shoots and kills Geoffrey Hammond, a family friend and neighbor. When her husband Robert returns home, Leslie claims that Hammond attempted to assault her, presenting herself as a victim defending her honor. However, as the investigation unfolds, it's revealed that Leslie and Hammond were having an affair, and she shot him in a jealous rage after discovering he was leaving her for another woman. The discovery of a compromising letter written by Leslie to Hammond threatens to expose her lies and destroy her carefully constructed facade of respectability.

About the Production

This was one of the early sound films produced during the transition from silent to talkies. The film was originally shot as a silent movie but was partially reshot with sound sequences, making it a part-talkie. Jeanne Eagels' performance was particularly notable as she brought her acclaimed stage acting background to this early sound production. The production faced challenges with the new sound technology, requiring actors to stand near hidden microphones and limiting camera movement compared to silent films.

Historical Background

The film was produced during a pivotal moment in cinema history - the transition from silent films to sound in 1929. This period, often called the 'talkie revolution,' was transforming Hollywood and putting many silent film stars out of work while creating new opportunities for stage actors like Jeanne Eagels. The stock market crash of October 1929 occurred just months after the film's release, marking the beginning of the Great Depression that would dramatically affect the film industry. The pre-Code era allowed filmmakers to explore more adult themes like adultery, murder, and moral ambiguity, which 'The Letter' embraced fully. The setting in British Malaya reflected colonial attitudes of the era, presenting an exotic backdrop for Western stories of passion and crime.

Why This Film Matters

As an early sound drama, 'The Letter' represents an important transitional work in cinema history, showcasing how filmmakers adapted theatrical works to the new medium of sound film. Jeanne Eagels' performance demonstrated how stage actors could successfully transition to movies, influencing future casting decisions. The film's exploration of female sexuality, passion, and violence was groundbreaking for its time, pushing boundaries of what was acceptable on screen. Its status as Eagels' final performance added to its cultural impact, creating a tragic legend around the actress. The film's preservation and rediscovery have made it an important document of early sound cinema techniques and acting styles, studied by film historians and scholars interested in the technical and artistic challenges of the early talkie era.

Making Of

The production of 'The Letter' occurred during the chaotic transition period from silent films to talkies. Paramount Pictures, like other studios, was scrambling to convert their facilities and talent to accommodate sound recording. The filming process was grueling for the actors, particularly Jeanne Eagels, who had to adapt her theatrical acting style to the more intimate medium of film while being constrained by the limitations of early sound equipment. The microphones were hidden in flower pots, lamps, and even in the actors' clothing, forcing them to remain relatively stationary during dialogue scenes. Eagels, known for her powerful stage presence, struggled with these technical constraints but delivered a performance that critics praised for its intensity and emotional depth. The production team had to experiment with various sound recording techniques, and the film includes both synchronized dialogue and musical sequences with intertitles, typical of early part-talkie productions.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Harry Fischbeck reflects the transitional nature of early sound films, with more static camera work than late silent films due to the limitations of sound recording equipment. The lighting creates dramatic shadows and highlights that enhance the film's tense atmosphere, particularly in the murder scene and confrontations. The use of close-ups on Jeanne Eagels' face emphasizes her emotional performance, a technique carried over from silent cinema but enhanced by her ability to deliver dialogue. The tropical setting is suggested through set design and lighting rather than location shooting, typical of the period. The film's visual style bridges the gap between the expressive cinematography of late silent films and the more realistic approach that would develop in sound cinema.

Innovations

As an early sound film, 'The Letter' represents the technical experimentation of the transition period. The production used early sound-on-disc technology, which required careful synchronization between the film projection and phonograph records. The film's sound engineers developed innovative techniques for hiding microphones in the set design while maintaining visual continuity. The partial conversion from silent to sound during production demonstrated the industry's rapid adaptation to new technology. The film's successful integration of dialogue, music, and sound effects, despite technical limitations, contributed to the development of sound film techniques that would become standard in the 1930s.

Music

The film featured a synchronized musical score and sound effects, typical of early part-talkies. The music was composed by Karl Hajos, who created dramatic underscoring that heightened the emotional impact of key scenes. The sound design included gunshots, door slams, and other environmental sounds that added realism to the production. Some scenes featured full dialogue, while others retained intertitles with musical accompaniment. The transition between silent and sound sequences was sometimes jarring, reflecting the experimental nature of early sound films. The film also included diegetic music, such as piano playing in social scenes, which helped establish the colonial setting and social atmosphere.

Famous Quotes

With all my heart, I still love the man I killed!

Don't you understand? I had to do it! He was leaving me!

I've learned that in the tropics, passion is as dangerous as the jungle itself.

A woman's reputation is everything - and I've lost mine forever.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening murder sequence where Leslie Crosbie shoots Geoffrey Hammond on the veranda, captured with dramatic lighting and Eagels' intense performance

- The courtroom scene where the compromising letter is revealed, destroying Leslie's carefully constructed story

- The final confrontation between Leslie and her husband, where the full truth of her deception comes to light

Did You Know?

- This was Jeanne Eagels' final film performance - she died of a heroin overdose in October 1929, just six months after the film's release

- Eagels received a posthumous Academy Award nomination for Best Actress for this performance, making her the first actor to be nominated posthumously

- The film was based on a 1927 play by W. Somerset Maugham, which was itself inspired by a real-life murder case in Malaya

- The original Broadway production starred Katharine Cornell, who was considered for the film role before Eagels was cast

- This version was considered lost for decades but was rediscovered and preserved in the 1990s

- The film was remade in 1940 with Bette Davis in the lead role, which became much more famous than the original

- Jeanne Eagels was a renowned stage actress who had only made a few films before this one, making her transition to sound particularly remarkable

- The film's sound technology was so new that many theaters were not yet equipped to show it, limiting its initial distribution

- Herbert Marshall, who played the husband, would later star in the 1940 remake but in a different role (as the lover)

- The controversial subject matter of adultery and murder was quite daring for 1929, even in the pre-Code era

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Jeanne Eagels' performance as 'electrifying' and 'powerful,' with many noting how successfully she transferred her stage magnetism to the screen. Variety called her performance 'a revelation' and predicted it would establish her as a major film star. The New York Times highlighted the film's tense atmosphere and Eagels' ability to convey complex emotions through both dialogue and silent moments. However, some critics found the film's static camera work and primitive sound techniques distracting. Modern critics, when the film was rediscovered, have praised it as a fascinating example of early sound cinema and a showcase for Eagels' tragically brief but brilliant film career, though many note that the 1940 remake surpassed it in technical sophistication.

What Audiences Thought

The film generated considerable public interest due to Jeanne Eagels' reputation as a celebrated stage actress making the transition to films. Audiences were drawn to the scandalous story and Eagels' intense performance. The film performed moderately well at the box office, particularly in urban theaters equipped for sound. After Eagels' death in October 1929, public interest in the film increased, with many viewing it as her final artistic statement. The tragic circumstances surrounding her death added to the film's mystique and lasting appeal among classic film enthusiasts. However, the film's reputation was eventually overshadowed by the more famous 1940 remake, leading to its relative obscurity until its rediscovery decades later.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- W. Somerset Maugham's 1927 play

- Real-life murder case in Malaya

- German Expressionist cinema (visual style)

- Victorian melodrama (narrative structure)

This Film Influenced

- The Letter (1940)

- Jezebel (1938)

- The Scarlet Letter (various versions)

- Film noir of the 1940s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film was considered lost for many years but was rediscovered in the 1990s. A 35mm print was found and preserved by the UCLA Film and Television Archive. The film has been restored and is available for viewing through film archives and special screenings. However, some deterioration is evident in the surviving print, particularly in the sound quality of some scenes. The preservation status is considered stable, with copies maintained at major film archives including the Library of Congress and UCLA.