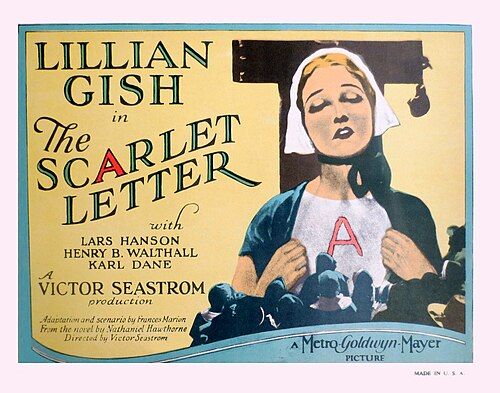

The Scarlet Letter

Plot

In 17th century Puritan Boston, Hester Prynne is found guilty of adultery and condemned to wear a scarlet letter 'A' on her dress as a mark of shame. She refuses to name her lover, who is revealed to be the town's beloved minister, Reverend Arthur Dimmesdale, tormented by guilt but too cowardly to confess. Hester's long-lost husband, Roger Chillingworth, arrives in Boston, discovers the truth, and vows revenge by becoming Dimmesdale's physician and psychological tormentor. The story follows the emotional and psychological struggles of all three characters as they deal with sin, guilt, revenge, and redemption in the harsh Puritan society. The film culminates in a dramatic confession on the scaffold where Dimmesdale finally admits his sin before dying in Hester's arms, while Chillingworth is left defeated and alone.

About the Production

The film was one of several literary adaptations that MGM produced in the mid-1920s to elevate cinema's cultural status. Director Victor Sjöström was brought from Sweden specifically for this project. Lillian Gish had significant creative input and was instrumental in bringing Sjöström to Hollywood. The production featured elaborate sets designed to recreate 17th century Puritan Boston with particular attention to historical accuracy in costumes and architecture.

Historical Background

The Scarlet Letter was produced during the mid-1920s 'Golden Age of Hollywood' before the transition to sound films. The era was characterized by economic prosperity, cultural change, and cinema's emergence as a dominant art form. Major studios like MGM sought to produce prestigious literary adaptations to legitimize cinema. The 1920s also saw increased social conservatism in America, with the rise of fundamentalist Christianity and moral reform movements, making the choice to adapt Hawthorne's novel about adultery and hypocrisy in Puritan society particularly relevant. The film reflected contemporary tensions between traditional values and modern sensibilities, as well as Hollywood's efforts to balance artistic ambition with commercial appeal. The production occurred during a period when European directors like Sjöström were being recruited by American studios to bring their artistic sensibilities to Hollywood productions.

Why This Film Matters

The Scarlet Letter represents an important moment in the history of literary adaptations in American cinema. As one of the first major Hollywood productions to tackle a classic American novel, it set a precedent for future adaptations and demonstrated cinema's potential to interpret serious literature. The film exemplifies the cross-cultural exchange that characterized Hollywood in the 1920s, with a Swedish director interpreting an American literary classic. Gish's portrayal of Hester Prynne became one of her most iconic roles, reinforcing her status as one of silent cinema's greatest dramatic actresses. The film's visual style, particularly Sjöström's use of natural lighting and outdoor locations, influenced subsequent historical dramas. As a silent adaptation of a verbally rich novel, it demonstrated how visual storytelling could convey complex emotional and moral themes without dialogue.

Making Of

The making of 'The Scarlet Letter' was marked by the collaboration of three master artists: director Victor Sjöström, star Lillian Gish, and cinematographer Hendrik Sartov. Sjöström brought his distinctive visual style to Hollywood, emphasizing naturalistic acting and atmospheric compositions. Gish, who had significant creative control over her projects at MGM, insisted on Sjöström as director after seeing his Swedish films. The production faced challenges recreating 17th century Puritan Boston, with extensive research into colonial architecture and clothing. Hanson, who spoke limited English, worked with a language coach to deliver his performance through pantomime and expression. The relationship between Gish and Sjöström was reportedly tense due to their strong artistic visions, but they created what many consider one of the finest adaptations of Hawthorne's novel. The climactic scaffold scene required careful choreography and emotional intensity from all three principal actors.

Visual Style

The cinematography was handled by Hendrik Sartov, a Danish cinematographer who frequently worked with Gish. Sartov employed naturalistic lighting techniques innovative for the time, using actual sunlight and practical lighting rather than harsh studio lighting. The film features many exterior scenes shot on location, giving it visual authenticity distinguishing it from most studio-bound productions. Sartov's camera work is characterized by subtle mobility and expressive compositions, with careful attention to how light and shadow convey emotional states. The cinematography particularly excels in scenes of isolation and psychological torment, using visual elements to externalize characters' inner conflicts. The visual style reflects Sjöström's Swedish background, with emphasis on natural landscapes and atmospheric effects. The use of soft focus and careful framing creates a dreamlike quality enhancing the story's emotional intensity.

Innovations

The Scarlet Letter showcased several technical achievements for its time. The production design created a convincing recreation of 17th century Puritan Boston, with detailed sets and props reflecting extensive historical research. The cinematography employed advanced lighting techniques, including natural light and controlled artificial lighting to create mood and atmosphere. The film demonstrated sophisticated editing techniques for the era, with smooth transitions between scenes and effective use of cross-cutting to build dramatic tension. The makeup effects, particularly those used to suggest passage of time and physical decline, were notably subtle and realistic compared to heavy makeup often seen in silent films. The preservation of the original negative has allowed modern audiences to appreciate the full visual quality of the production, remarkable for its time.

Music

As a silent film, The Scarlet Letter originally had no synchronized soundtrack but would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters. The score varied by theater, with larger venues employing full orchestras and smaller houses using pianists or organists. The film's emotional tone suggested a dramatic, classical-style score with themes for main characters and mood music for key scenes. Modern restorations have featured newly composed scores, including a 1995 version with music by Gillian Anderson attempting to recreate 1920s musical style. Original cue sheets for theater musicians, if they exist, would have provided suggestions for appropriate musical pieces to accompany specific scenes. The lack of recorded dialogue made visual storytelling and musical accompaniment particularly important in conveying emotional and narrative content.

Famous Quotes

"On the breast of her gown, in fine red cloth, surrounded with an elaborate embroidery and fantastic flourishes of gold thread, appeared the letter A."

"She had not known the weight until she felt the freedom."

"No man, for any considerable period, can wear one face to himself and another to the multitude, without finally getting bewildered as to which may be the true."

"It is to the credit of human nature, that, except where its selfishness is brought into play, it loves more readily than it hates."

"There is a moral to everything, if we would only avail ourselves of it."

Memorable Scenes

- The opening scene where Hester Prynne emerges from prison with her infant daughter, wearing the scarlet letter for the first time as townspeople stare and judge her

- The night scene on the scaffold where Hester, Dimmesdale, and Pearl stand together under the stars, a moment of secret unity and emotional intensity

- The scene where Chillingworth discovers the identity of Pearl's father by observing Dimmesdale's physical and emotional distress

- The climactic confession scene on the scaffold where Dimmesdale finally reveals his sin to the townspeople before dying

- The final scene showing Hester and Pearl leaving Boston, suggesting the possibility of a new beginning away from judgment and hypocrisy

Did You Know?

- This was Victor Sjöström's second American film after coming to Hollywood from Sweden, where he was already an acclaimed director

- Lillian Gish had previously played Hester Prynne in a 1911 adaptation, making this her second time portraying the character

- The film was considered daring for its time due to its themes of adultery and moral hypocrisy in a religious community

- MGM originally wanted Gish to star in 'The Merry Widow' (1925) but she refused, preferring serious dramatic films

- Lars Hanson, who played Dimmesdale, was also Swedish and had worked with Sjöström in Sweden before coming to Hollywood

- The film was shot during the transition period to sound films, which would soon revolutionize the industry

- Some outdoor scenes were filmed at the Paramount Ranch in Agoura Hills, California

- The film's intertitles were written by Marian Ainslee, who worked on many MGM productions

- The costume design was by Adrian, who would become one of Hollywood's most famous costume designers

- The film's original negative was preserved by MGM and later restored by the George Eastman Museum

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its artistic ambition and powerful performances. The New York Times highlighted Sjöström's 'masterful direction' and Gish's 'haunting portrayal' of Hester Prynne. Variety called it 'one of the finest literary adaptations yet produced by Hollywood' and praised its visual beauty and emotional depth. Modern critics continue to appreciate the film, with many considering it one of the greatest silent dramas ever made. It's often cited as a high point in both Gish's career and Sjöström's Hollywood period. Critics particularly note the film's atmospheric cinematography, restrained yet powerful performances, and faithful yet cinematic interpretation of Hawthorne's novel. Some contemporary reviewers criticized the film for being too somber and slow-paced, but most recognized its artistic merits.

What Audiences Thought

Audiences in 1926 responded positively to the film, particularly fans of Lillian Gish who appreciated her choice of serious dramatic roles over lighter fare. The film's adult themes and serious tone limited its commercial potential compared to more escapist entertainment, but it found an appreciative audience among educated viewers and literary enthusiasts. The film's reputation has grown over time, with silent film enthusiasts and scholars regarding it as a masterpiece of the era. Modern audiences viewing the film in revival screenings or on home media have generally responded positively to its emotional power and visual beauty, though some find its pacing challenging by contemporary standards. The film remains a favorite among fans of silent cinema and is frequently shown at film festivals and museums specializing in classic films.

Awards & Recognition

- No major awards documented - the first Academy Awards were held in 1929, after this film's release

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Nathaniel Hawthorne's 1850 novel 'The Scarlet Letter'

- Victor Sjöström's Swedish filmmaking background and naturalistic style

- German Expressionist cinema's use of visual elements to convey psychological states

- Lillian Gish's experience in silent drama and work with D.W. Griffith

This Film Influenced

- Subsequent adaptations of classic literature in Hollywood

- Historical dramas like 'The Ten Commandments' (1923) and 'The King of Kings' (1927)

- Films dealing with moral and religious themes

- Later dramatic films featuring psychological depth

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Scarlet Letter is well-preserved, with a complete nitrate negative held in the MGM/United Artists archive (now part of Warner Bros.). The film has been restored several times, most notably by the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York. The restoration work has preserved the film's visual quality and allowed for modern screenings and home video releases. The film is not considered lost or partially lost, unlike many silent films from the same period. The preservation of this film is particularly valuable as it represents one of the finest examples of late silent cinema and a key work in both Victor Sjöström's and Lillian Gish's careers.