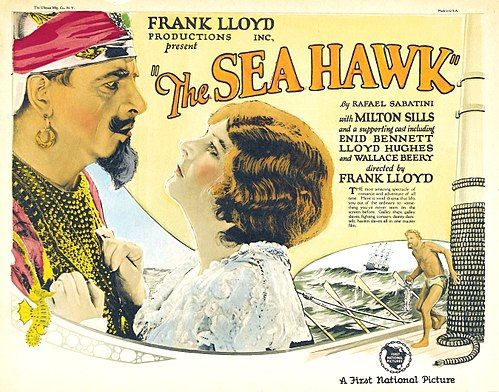

The Sea Hawk

"A Thrilling Saga of the Sea and Vengeance!"

Plot

The Sea Hawk (1924) follows the dramatic transformation of Oliver Tressilian, a proud English gentleman from Cornwall who is betrayed by his own half-brother Lionel and falsely accused of treason. After being shanghaied and sold into slavery, Oliver endures brutal conditions as a galley slave aboard a Spanish ship until he leads a successful mutiny and embraces a new identity as 'Sakr-el-Bahr' (The Sea Hawk), a feared Barbary corsair. As captain of a Moorish fighting ship, he seeks revenge against those who wronged him while navigating complex political intrigues between England, Spain, and the Barbary states. The film culminates in spectacular naval battles and personal confrontations as Oliver must choose between his quest for vengeance and his lingering love for his former fiancée Rosamund, who has been caught in the web of political machinations.

About the Production

The film featured elaborate full-scale ship constructions and sophisticated miniature effects for the naval battle sequences. Director Frank Lloyd insisted on realistic maritime elements, hiring actual sailors as extras and consultants. The production faced challenges with creating convincing storm sequences, which were achieved using large water tanks, wind machines, and innovative camera techniques. The galley slave scenes were particularly grueling to film, with the actors spending long hours in cramped, hot conditions to achieve authenticity.

Historical Background

The Sea Hawk was produced during the golden age of silent cinema in 1924, a period when Hollywood was establishing itself as the global center of film production. The early 1920s saw a fascination with historical adventure epics, reflecting America's growing confidence as a world power following World War I. The film's themes of betrayal, redemption, and cultural conflict resonated with audiences still processing the war's aftermath. The Barbary corsair setting allowed filmmakers to explore exotic locations and cultures without leaving California, capitalizing on the public's appetite for escapism. The film's production coincided with significant technical advancements in cinema, including improved lighting, more sophisticated camera movements, and better special effects techniques. 1924 was also the year before the birth of the Academy Awards, and films like The Sea Hawk helped establish the criteria for what constituted cinematic excellence.

Why This Film Matters

The Sea Hawk represents a pinnacle of silent adventure filmmaking and helped establish the swashbuckler genre as a major force in Hollywood cinema. Its success demonstrated the commercial viability of large-scale historical epics, paving the way for later classics like Douglas Fairbanks' The Black Pirate (1926) and eventually the 1940 sound remake starring Errol Flynn. The film's complex narrative structure, combining personal drama with spectacular action sequences, influenced how adventure stories would be told in cinema. It also contributed to the popular image of the romantic pirate in American culture, blending historical elements with fictional heroism. The film's technical achievements in maritime cinematography set new standards for how water sequences could be filmed, techniques that would influence naval films for decades. Its portrayal of cultural conflict between Christian Europe and the Islamic world reflected and shaped 1920s American attitudes toward international relations.

Making Of

The production of The Sea Hawk was an ambitious undertaking that pushed the boundaries of silent filmmaking. Director Frank Lloyd, known for his meticulous attention to detail, spent months researching historical maritime practices and Barbary corsair culture. The ship sets were constructed to full scale on specially built tanks at the studio, allowing for realistic water effects and battle sequences. The cast underwent extensive training in sailing and rope work to appear authentic. Wallace Beery, who played the treacherous Jasper Leigh, reportedly maintained his villainous persona off-camera to enhance his performance intensity. The galley slave sequences were particularly challenging, with actors spending hours in cramped conditions to achieve the desired realism. The film's cinematographer, James Wong Howe, experimented with new camera techniques for the storm sequences, including mounting cameras on moving platforms to simulate the ship's motion. The production also employed a full orchestra during filming to help actors maintain the proper emotional rhythm for their silent performances.

Visual Style

The cinematography of The Sea Hawk, helmed by James Wong Howe and Norbert Brodine, was groundbreaking for its time, particularly in the maritime sequences. The film employed innovative techniques for capturing ocean scenes, including the use of multiple cameras on moving platforms to simulate the motion of ships at sea. The storm sequences utilized revolutionary lighting effects, combining arc lights with filters to create dramatic contrasts between light and shadow. The cinematographers experimented with underwater photography for certain scenes, a technique still in its infancy during the silent era. The galley sequences used claustrophobic camera angles and tight framing to convey the oppressive conditions of slavery. The battle scenes employed long shots to establish scale mixed with dynamic close-ups during combat sequences. The film's visual style helped establish the cinematic language for maritime adventure films that would influence the genre for decades.

Innovations

The Sea Hawk pioneered several technical innovations in silent filmmaking, particularly in the realm of special effects and maritime cinematography. The production team developed new techniques for creating realistic ocean effects using large tanks and wave machines that could generate waves up to eight feet high. The miniature ship models used for distant shots were among the most sophisticated of their time, featuring working sails and detailed rigging that could be manipulated to simulate battle damage. The film employed an early version of the process shot for certain scenes, allowing actors to appear to be climbing tall masts when they were actually working on safer, lower sets. The storm sequences utilized multiple fans, water cannons, and moving platforms to create the illusion of a ship in a tempest. The galley slave sequences featured innovative camera mounting techniques that could move through the cramped spaces while maintaining focus. These technical achievements earned special recognition from industry organizations and influenced subsequent maritime films.

Music

As a silent film, The Sea Hawk was originally presented with live musical accompaniment that varied by theater. The official cue sheet provided by First National Pictures recommended themes for different scenes, including dramatic orchestral pieces for battle sequences, romantic melodies for the love scenes, and ominous motifs for the villain's appearances. Major theaters typically employed full orchestras, while smaller venues used piano or organ accompaniment. The score incorporated popular classical pieces of the era alongside original compositions. Notably, the film's storm sequences were often accompanied by Wagner's 'Ride of the Valkyries,' while the romantic moments featured adaptations of Chopin's nocturnes. The musical direction emphasized the film's emotional arc, with the score becoming more complex and layered as Oliver Tressilian's journey progressed from English gentleman to corsair captain.

Famous Quotes

A man is not beaten until he gives up the fight.

The sea is a cruel mistress, but she is honest in her cruelty.

Revenge is a dish best served from the deck of a fast ship.

In chains or in command, a man must know his own worth.

The wind cares not for flags, only for sails that can catch it.

Memorable Scenes

- The spectacular mutiny sequence where Oliver Tressilian leads the galley slaves to freedom, featuring intense close-ups of desperate faces and dramatic shots of the ship's takeover

- The massive naval battle between the Moorish corsair fleet and Spanish warships, utilizing innovative special effects and hundreds of extras

- The transformation scene where Oliver adopts his new identity as Sakr-el-Bahr, complete with costume change and symbolic shedding of his English past

- The emotional reunion scene between Oliver and Rosamund in the Moorish palace, showcasing the romantic tension and cultural divide between them

- The climactic sword fight between Oliver and his treacherous brother Lionel, choreographed with precision and filmed with dynamic camera movement

Did You Know?

- This was one of the most expensive films of 1924, with its massive ship sets costing over $75,000 alone

- Wallace Beery's performance as the villainous Jasper Leigh was so menacing that it typecast him in similar roles for years

- The film's success led to a sequel 'The Sea Hawk Returns' being planned but never produced

- Milton Sills performed many of his own stunts, including several dangerous scenes on the ship's rigging

- The naval battle sequences used over 200 extras and multiple full-scale ships

- Director Frank Lloyd won his first Academy Award the following year for 'The Divine Lady', building on the success of this film

- The original novel by Rafael Sabatini was heavily adapted for the screenplay, with several characters and subplots condensed or eliminated

- The film's premiere was held at the prestigious Grauman's Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood

- A young John Wayne worked as an extra on this film in one of his earliest uncredited roles

- The special effects team won special recognition from the American Society of Cinematographers for their innovative miniature work

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised The Sea Hawk as a masterpiece of silent cinema, with particular acclaim for its spectacular production values and compelling performances. The New York Times hailed it as 'a triumph of cinematic artistry' and 'one of the most impressive productions of the year.' Variety magazine praised Frank Lloyd's direction as 'masterful' and noted the film's 'unprecedented scale and ambition.' Modern critics and film historians continue to regard The Sea Hawk as a significant achievement in silent cinema, often citing it as an example of the genre at its finest before the transition to sound. The film is frequently mentioned in scholarly works about silent epics and is studied for its innovative cinematography techniques. However, some contemporary critics note that certain plot elements and characterizations reflect the racial and cultural attitudes of the 1920s, which modern viewers may find problematic.

What Audiences Thought

The Sea Hawk was a tremendous commercial success upon its release, becoming one of the highest-grossing films of 1924. Audiences were particularly captivated by the thrilling naval battle sequences and the charismatic performance of Milton Sills in the lead role. The film ran for months in major cities and was frequently re-booked due to popular demand. Contemporary newspaper accounts report that theater owners often had to turn away patrons during peak showings. The film's success helped establish Milton Sills as a major star and solidified Wallace Beery's reputation as one of Hollywood's premier villains. Audience letters published in fan magazines of the era frequently praised the film's spectacle and emotional impact. The Sea Hawk developed such a strong following that it was periodically revived in theaters throughout the late 1920s, even as sound films began to dominate the market.

Awards & Recognition

- Photoplay Magazine Medal of Honor (1924) - Winner

- Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Special Recognition for Technical Achievement (1925) - Winner

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Rafael Sabatini's novel of the same name

- Douglas Fairbanks' The Mark of Zorro (1920)

- The Prisoner of Zenda (1922)

- Robin Hood (1922)

- The Three Musketeers (1921)

This Film Influenced

- The Black Pirate (1926)

- The Sea Hawk (1940 remake)

- Captain Blood (1935)

- The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

- Against All Flags (1952)

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The Sea Hawk is considered a partially lost film. While approximately 75% of the original footage survives in various archives, some sequences, particularly the complete naval battle scenes, exist only in fragmentary form. The surviving elements are held by several institutions including the Library of Congress, the UCLA Film and Television Archive, and the Museum of Modern Art. A restoration effort in the 1990s combined surviving elements from multiple sources to create the most complete version currently available, though some scenes remain represented by still photographs and intertitles. The film is listed on the National Film Preservation Foundation's priority list for complete restoration.