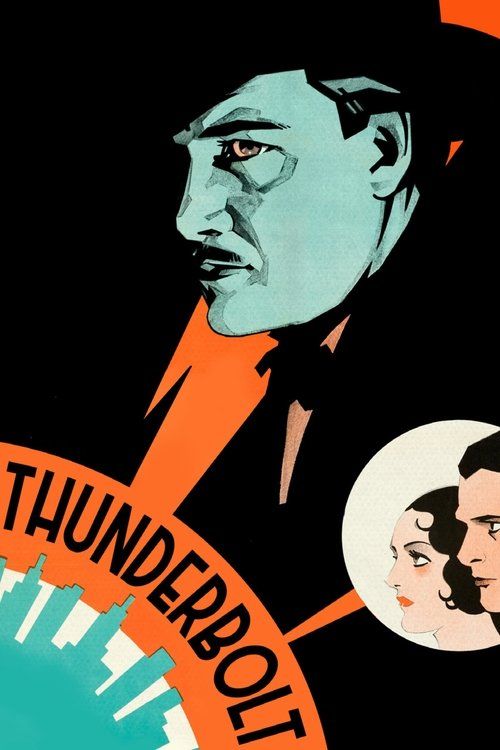

Thunderbolt

"His love was a thunderbolt that shattered two lives!"

Plot

Thunderbolt Jim Lang, a notorious criminal, is captured and sentenced to death for murder. In prison, he discovers that his girlfriend Ritzy has fallen in love with Bob Moran, an innocent man framed for a crime and imprisoned in the cell next to Thunderbolt's. Consumed by jealousy and rage, Thunderbolt uses his remaining time to manipulate prison officials and fellow inmates to create opportunities to kill Bob before his own execution. The film becomes a tense psychological battle as Bob tries to survive both the corrupt prison system and Thunderbolt's murderous intentions, while Ritzy desperately works to prove Bob's innocence from the outside.

About the Production

Thunderbolt was filmed during the challenging transition from silent to sound cinema, requiring the production to create both silent and sound versions. Director Josef von Sternberg, known for his meticulous visual style, had to adapt his techniques to accommodate the new sound technology while maintaining his artistic vision. The prison sequences were filmed on elaborate sets designed to maximize the claustrophobic atmosphere, with special attention to acoustics for the sound version. George Bancroft, who had worked with von Sternberg before, performed his own stunts during the intense prison fight scenes.

Historical Background

Thunderbolt was produced during one of the most transformative periods in cinema history - the transition from silent to sound films. Released in May 1929, it came just months before the stock market crash that would trigger the Great Depression, affecting both film production and audience attendance. The film reflected the growing public fascination with gangsters and crime, which would become a dominant genre in the early 1930s as audiences sought escapist entertainment during hard economic times. The prison setting and themes of justice versus corruption resonated with audiences questioning institutions during this period of social upheaval. The film's technical innovations in sound recording came at a time when Hollywood was rapidly developing new technologies, with studios investing heavily in sound equipment and theaters converting to accommodate talkies. Thunderbolt represents the sophistication of late silent cinema meeting the possibilities of sound, capturing a unique moment in film history when visual storytelling traditions merged with new audio capabilities.

Why This Film Matters

Thunderbolt holds an important place in cinema history as a bridge between silent and sound eras, showcasing how established directors like Josef von Sternberg adapted their artistic vision to new technologies. The film contributed to establishing the gangster genre as a significant American film form, influencing countless later crime films and proto-noir pictures. Von Sternberg's use of sound for psychological tension rather than mere spectacle demonstrated how audio could enhance cinematic storytelling beyond dialogue. The film's exploration of masculine rivalry, jealousy, and redemption within the prison setting created a template for later prison dramas. George Bancroft's performance as Thunderbolt established a new type of anti-hero - complex, menacing yet strangely sympathetic - that would influence characterizations in gangster films for decades. The film's technical achievements in early sound recording pushed the boundaries of what was possible, contributing to the rapid advancement of film technology during this period. Thunderbolt also represents the sophistication of late 1920s American cinema before the Production Code would severely restrict content in 1934.

Making Of

The production of Thunderbolt was fraught with challenges typical of the early sound era. Director Josef von Sternberg, renowned for his visual mastery in silent films, had to completely rethink his approach to accommodate sound recording. The studio insisted on both silent and sound versions being shot simultaneously, essentially requiring two productions. Von Sternberg fought with studio executives over artistic control, particularly regarding the use of sound effects and dialogue. George Bancroft, playing the intimidating Thunderbolt, reportedly stayed in character throughout filming, intimidating crew members and extras. The prison sets were designed with removable walls to accommodate the bulky sound equipment of the era. Fay Wray and Richard Arlen had to undergo extensive voice coaching for their dialogue scenes, as early sound recording was unforgiving of vocal imperfections. The electric chair scene required special effects that were groundbreaking for the time, using a combination of practical effects and camera tricks to create the illusion of electrocution without endangering the actors.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Thunderbolt, handled by Harold Rosson, showcases the visual sophistication of late silent cinema adapting to sound requirements. Rosson employed dramatic low-key lighting that would later influence film noir, particularly in the prison sequences where shadows create a sense of confinement and menace. The camera work is more restrained than typical silent films, as the need to accommodate sound recording equipment limited camera movement, but von Sternberg and Rosson turned this limitation into a strength, creating a more intense, claustrophobic visual style. The film features striking compositions that emphasize power dynamics, with Thunderbolt often shot from low angles to emphasize his dominance, while Bob is frequently shown in vulnerable positions. The electric chair sequence uses innovative lighting effects to simulate electricity without revealing the technical tricks. Despite the technical constraints of early sound filming, the cinematography maintains von Sternberg's characteristic visual poetry, with carefully composed frames that tell the story through images as much as through dialogue.

Innovations

Thunderbolt pioneered several technical innovations in early sound cinema. The production developed new microphone placement techniques, hiding recording devices in props and set pieces to allow for more natural actor movement and positioning. The film experimented with post-production sound mixing, layering dialogue, music, and effects to create a more complex auditory experience than typical early talkies. The prison sequences required innovative sound design to create the illusion of a large facility while recording on studio sets. The electric chair scene featured groundbreaking sound effects that simulated electrical discharge using a combination of mechanical devices and audio manipulation. The production also developed new methods for synchronizing sound with picture during editing, allowing for more precise timing of audio cues with visual elements. These technical achievements contributed to the film's reputation as one of the most sophisticated early sound productions and influenced subsequent developments in film sound technology.

Music

The soundtrack of Thunderbolt represents a significant achievement in early sound cinema. The musical score, composed by John Leipold, was one of the first to integrate music with diegetic sound in a sophisticated manner. Rather than simply providing background music, the score actively participates in the storytelling, with themes associated with each character that evolve throughout the film. The prison environment is brought to life through carefully crafted sound effects - the clanging of cell doors, the echoing footsteps in corridors, and the distant shouts of other prisoners create an immersive auditory experience. The film uses silence strategically, particularly in moments of tension, demonstrating an early understanding of how the absence of sound could be as powerful as its presence. The dialogue recording, while limited by early microphone technology, captures the raw emotion of the performances, with Bancroft's voice conveying menace and vulnerability in equal measure. The electric chair sequence features groundbreaking sound design that uses both musical and technical elements to create a terrifying auditory experience.

Famous Quotes

Thunderbolt: 'They call me Thunderbolt because when I strike, it's like lightning from a clear sky.'

Thunderbolt: 'In here, we're all dead men. Some just don't know it yet.'

Ritzy: 'You can't own people, Thunderbolt. Love doesn't work that way.'

Bob: 'I may die innocent, but I won't live guilty.'

Thunderbolt: 'The only thing worse than dying is knowing she'll be with you when I'm gone.'

Warden: 'Justice isn't about what you deserve. It's about what the system demands.'

Thunderbolt: 'In this place, hope is the cruelest torture of all.'

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence where Thunderbolt is captured in a dramatic police raid, showcasing von Sternberg's visual style and establishing the character's menacing presence

- The prison yard confrontation where Thunderbolt first learns of Bob's relationship with Ritzy, building tension through subtle glances and positioning

- The electric chair preparation scene, which uses sound design and lighting to create unbearable tension as Thunderbolt faces his execution

- The cell block sequence where Thunderbolt manipulates other inmates to isolate and terrorize Bob, demonstrating his power even in confinement

- The final confrontation between Thunderbolt and Bob, where both men face their mortality and find unexpected understanding

- Ritzy's desperate attempts to prove Bob's innocence from outside the prison, creating parallel action that heightens the drama

Did You Know?

- Thunderbolt was released in both silent and sound versions during the industry's transition period, with the sound version featuring synchronized dialogue and sound effects

- George Bancroft won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance, though it was technically for his body of work that year including this film

- Director Josef von Sternberg originally wanted Marlene Dietrich for the female lead, but Paramount insisted on Fay Wray, who was under contract

- The prison cell scenes were filmed with real microphones hidden in props, a revolutionary technique for early sound recording

- The film's success helped establish the gangster film genre, which would flourish in the early 1930s with films like Little Caesar and The Public Enemy

- Thunderbolt was one of the first films to use sound for psychological tension rather than just musical accompaniment

- The electric chair execution sequence was so realistic that it caused several audience members to faint during early screenings

- Fay Wray would later become famous for her role in King Kong (1933), but considered Thunderbolt one of her most challenging roles

- The film's original title was 'The Murderer' but was changed to Thunderbolt to emphasize Bancroft's character nickname

- Von Sternberg and Bancroft had previously collaborated on Underworld (1927), which helped establish the gangster film genre

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised Thunderbolt for its powerful performances and technical innovations. The New York Times hailed it as 'a triumph of the new sound medium' and particularly lauded George Bancroft's 'menacing yet nuanced portrayal of a criminal facing his end.' Variety noted that von Sternberg 'has successfully translated his visual mastery to the sound medium without sacrificing his artistic integrity.' Modern critics view Thunderbolt as a significant transitional work, with Film Quarterly calling it 'a fascinating document of cinema in flux, where the visual poetry of late silent cinema meets the psychological possibilities of sound.' The film is often cited in film studies as an example of how some directors successfully navigated the transition to sound while maintaining their artistic vision. Critics particularly praise the prison sequences for their claustrophobic atmosphere and innovative use of sound to create tension. The electric chair scene is frequently mentioned as one of the most powerful sequences in early sound cinema, demonstrating how sound could enhance dramatic impact beyond what was possible in silent films.

What Audiences Thought

Thunderbolt performed moderately well at the box office, particularly in urban areas where audiences were eager for sophisticated sound films. The film's adult themes and intense violence limited its appeal in smaller markets, where more family-friendly fare was preferred. Contemporary audience reactions were strong, with many viewers reportedly being deeply affected by the prison sequences and the execution scene. The dual release strategy (silent and sound versions) helped maximize attendance, as theaters not yet equipped for sound could still show the film. In major cities, the sound version drew larger crowds, with audiences particularly impressed by the quality of the audio and its integration with the visual storytelling. Modern audiences rediscovering Thunderbolt through film festivals and classic cinema screenings often express surprise at its sophistication and power, with many noting how it transcends the limitations of early sound technology to deliver a compelling dramatic experience. The film has developed a cult following among enthusiasts of early sound cinema and gangster film aficionados.

Awards & Recognition

- Academy Award for Best Writing (Original Story) - Jules Furthman

- Academy Award for Best Actor - George Bancroft (honorary, for body of work including Thunderbolt)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Underworld (1927) - von Sternberg's earlier gangster film

- The Docks of New York (1928) - another von Sternberg film exploring similar themes

- German Expressionist cinema - particularly in its use of shadows and psychological tension

- The Big House (1930) - influenced by Thunderbolt's prison setting

- Little Caesar (1931) - built on the gangster film foundation Thunderbolt helped establish

This Film Influenced

- The Big House (1930) - expanded on prison drama elements

- Scarface (1932) - developed the gangster genre Thunderbolt helped establish

- I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932) - explored institutional corruption themes

- Brute Force (1947) - prison drama with similar psychological elements

- Cool Hand Luke (1967) - explored similar themes of institutional dehumanization

- The Shawshank Redemption (1994) - prison drama with themes of hope and redemption

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Thunderbolt is preserved in the archives of major film institutions including the Library of Congress and the UCLA Film and Television Archive. Both the silent and sound versions have survived, though the sound version required significant restoration work due to deterioration of the early sound-on-disc recordings. In 2018, The Criterion Collection released a restored version on Blu-ray, featuring both versions of the film and extensive supplemental materials. The restoration process involved combining elements from multiple surviving prints to create the most complete version possible. The film is considered to be in good preservation status, with no risk of being lost, though some minor scenes remain missing from both versions. The restoration has been praised for its clarity and faithfulness to the original theatrical presentation.