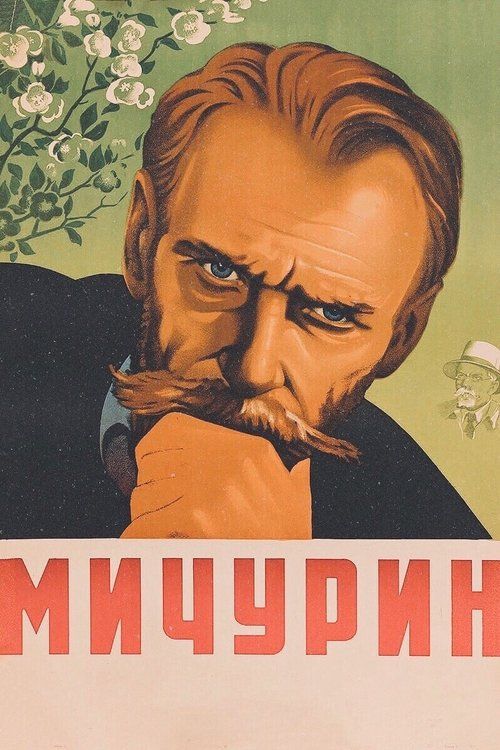

Life in Bloom

"The story of a man who taught nature to serve humanity"

Plot

The film chronicles the life of renowned Russian biologist Ivan Michurin, beginning in 1912 when he rejects lucrative American offers to work abroad, choosing instead to continue his research in the Russian Empire despite facing opposition from the tsarist government, church authorities, and idealistic scientists who dismiss his revolutionary approach to plant breeding. Michurin finds support from prominent Russian scientists who recognize the value of his work, enabling him to persevere through hardship and continue his experiments in creating new plant varieties through selective breeding and hybridization techniques. The narrative follows his struggles against scientific conservatism and bureaucratic obstacles, showcasing his dedication to improving agriculture and food production through his innovative methods. Following the October Revolution, Michurin's small private garden in his hometown of Kozlov transforms into a large state-supported nursery, allowing his work to flourish on an unprecedented scale and benefit the entire Soviet Union. The film culminates with Michurin's triumph as his theories gain widespread acceptance and his plant varieties contribute significantly to Soviet agriculture, cementing his legacy as a pioneer of Soviet biological science.

About the Production

The film was one of the last major works by director Oleksandr Dovzhenko before his death in 1956. Production involved extensive research into Michurin's life and work, with consultation from botanical experts. The filming required careful recreation of early 20th century scientific environments and the transformation of Michurin's garden over decades. Dovzhenko faced pressure from Soviet authorities to present Michurin's work in alignment with Lysenkoism, the controversial biological theory promoted by Trofim Lysenko that was officially endorsed by Stalin.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the early Cold War period when the Soviet Union was emphasizing its scientific and technological achievements as evidence of socialism's superiority. 1948 was particularly significant as it marked the height of the Lysenko affair, when Trofim Lysenko's pseudoscientific theories about agriculture were officially endorsed by Stalin, leading to the persecution of geneticists and other mainstream biologists. The film's portrayal of Michurin as a self-taught genius who triumphed over 'bourgeois science' served to legitimize Lysenko's anti-genetics stance. Post-war reconstruction was underway, and the Soviet government was promoting agricultural self-sufficiency through scientific innovation. The film also reflected the Soviet cult of the scientist-hero, presenting Michurin as an exemplar of the new Soviet man who could transform nature through will and socialist principles. This period saw increased state control over all aspects of cultural production, with cinema serving as a key tool for ideological education and the promotion of Soviet values.

Why This Film Matters

'Life in Bloom' holds a unique place in Soviet cinema as one of the most elaborate biographical films produced during the Stalin era. It represents the intersection of art, science, and politics in Soviet culture, demonstrating how cinema was used to shape public understanding of scientific issues. The film contributed to the Michurin cult in the Soviet Union, with his name becoming synonymous with Soviet agricultural science for decades. It influenced public perception of biology and genetics, supporting the official narrative that rejected Mendelian genetics in favor of Lysenkoism. The film's visual style and approach to scientific storytelling influenced subsequent Soviet productions about scientists and inventors. Its success demonstrated the effectiveness of the biographical genre for promoting Soviet values and achievements. The film also serves as a historical document of how the Soviet state attempted to control and direct scientific discourse through cultural means. Today, it is studied by film scholars and historians as an example of how art can be co-opted for political purposes while still retaining artistic merit.

Making Of

The production of 'Life in Bloom' was a major undertaking for Soviet cinema, involving multiple studios and extensive location shooting. Director Oleksandr Dovzhenko, known for his poetic approach to filmmaking, faced the challenge of creating a compelling biographical drama while adhering to the strict requirements of socialist realism. The production team consulted with botanists and historians to ensure accuracy in depicting Michurin's experiments and the scientific atmosphere of the era. Filming took place over several months across different seasons to capture the various stages of plant growth central to Michurin's work. The cast underwent extensive preparation, with lead actor Vladimir Solovyov studying botanical principles to convincingly portray the scientific aspects of Michurin's character. The film's production coincided with a period of intense political pressure on Soviet scientists, particularly regarding genetics, which influenced how Michurin's theories were presented. Despite these constraints, Dovzhenko managed to infuse the film with his characteristic visual poetry and humanistic perspective, creating a work that transcended mere propaganda.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Yevgeni Andrikanis is considered one of the film's strongest artistic elements, featuring sweeping shots of the Russian landscape and intimate close-ups of plants and scientific experiments. The film employs innovative techniques for depicting plant growth, including time-lapse photography and microscopic imagery that were advanced for the period. The visual style transitions from the muted colors of pre-revolutionary Russia to the vibrant, sun-drenched scenes of the Soviet era, symbolizing the transformation brought by the revolution. Andrikanis uses lighting to create dramatic contrasts between the darkness of Michurin's early struggles and the brightness of his later triumphs. The camera work emphasizes the connection between human labor and natural growth, with many shots framed to show scientists working alongside their plant subjects. The film's visual composition reflects Dovzhenko's poetic sensibility, with carefully composed tableaus that elevate ordinary scientific work to mythic proportions.

Innovations

The film pioneered several technical innovations in Soviet cinema, particularly in the filming of biological processes. The production team developed specialized camera rigs and lighting equipment to capture time-lapse photography of plant growth over extended periods. Microscopic cinematography was used to show cellular processes, requiring custom-built adapters for the film cameras. The film's special effects team created seamless transitions between different historical periods using innovative optical printing techniques. The sound recording equipment was modified to capture subtle sounds of plant growth and laboratory work, adding to the film's scientific authenticity. The production also developed new methods for creating artificial weather conditions on set, allowing for year-round filming of seasonal agricultural scenes. These technical achievements were later documented in Soviet film journals and influenced subsequent scientific and educational films.

Music

The musical score was composed by Dmitri Kabalevsky, one of the Soviet Union's most prominent composers, who created a sweeping orchestral score that blends Russian folk motifs with modernist elements. The music emphasizes the film's themes of struggle and triumph, with leitmotifs associated with Michurin's scientific breakthroughs and the growth of his plants. The soundtrack incorporates authentic Russian folk songs and revolutionary anthems to ground the story in its historical context. Kabalevsky's use of brass instruments and percussion during scenes of scientific discovery creates a sense of industrial progress and Soviet achievement. The score also features delicate woodwind passages during scenes of plant cultivation, emphasizing the harmony between human intervention and natural processes. The soundtrack was recorded by the Moscow State Symphony Orchestra and was later released as a separate album, becoming popular in its own right.

Famous Quotes

"We cannot wait for nature to give us what we need - we must help nature, guide it, teach it!"

"Science has no homeland, but the scientist has a duty to his people."

"They call me a dreamer, but every great discovery begins with a dream."

"A plant is like a person - it needs care, understanding, and the right conditions to flourish."

"The revolution has given us not just freedom, but the means to transform our world."

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing Michurin rejecting American offers, emphasizing his patriotism and dedication to his homeland

- The time-lapse photography sequence showing one of Michurin's hybrid plants growing from seed to fruit over several seasons

- The scene where Michurin defends his theories against skeptical academic scientists in a dramatic conference setting

- The transformation of Michurin's small private garden into a massive state nursery after the revolution

- The final scene showing the widespread success of Michurin's plant varieties across Soviet collective farms

Did You Know?

- The film's original Russian title 'Жизнь в цвету' literally translates to 'Life in Bloom,' but it was also known internationally as 'Michurin.'

- Director Oleksandr Dovzhenko initially hesitated to make the film, as he preferred working on original stories rather than biographical pictures.

- The film was heavily promoted by Soviet authorities as an example of 'socialist realism' in cinema, celebrating the achievements of Soviet science.

- Ivan Michurin's actual botanical garden in Michurinsk (formerly Kozlov) was used as a filming location for several scenes.

- The film's release coincided with the height of the Lysenko affair in Soviet biology, making its scientific content politically significant.

- Vladimir Solovyov, who played Michurin, spent months studying the biologist's mannerisms and speech patterns from archival photographs and recordings.

- The film was one of the most expensive Soviet productions of 1948, with extensive sets built to recreate different historical periods.

- Several scenes featuring Michurin's experiments were filmed using time-lapse photography to show plant growth over extended periods.

- The film's premiere was attended by numerous Soviet scientists and government officials, including representatives from the Soviet Academy of Sciences.

- Despite being a state-sponsored production, the film contains subtle criticisms of bureaucratic obstacles to scientific progress.

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film as a masterpiece of socialist realism, particularly highlighting Dovzhenko's direction and Solovyov's performance. Pravda and other official newspapers lauded the film for its faithful portrayal of a Soviet scientific hero and its contribution to the ideological education of Soviet citizens. Western critics had limited access to the film initially, but those who saw it noted its technical excellence and powerful visual imagery, while questioning its historical accuracy and political messaging. Later Soviet critics, particularly after the de-Stalinization period, re-evaluated the film more critically, acknowledging its artistic merits while noting its role in promoting Lysenkoism. Modern film scholars recognize the film as a complex work that balances artistic vision with ideological requirements, with many considering it one of Dovzhenko's most accomplished later works despite its propagandistic elements. The film's cinematography and visual composition have been consistently praised across different critical eras.

What Audiences Thought

The film was extremely popular with Soviet audiences upon its release, drawing large crowds in major cities and throughout the republics. Many viewers, particularly those involved in agriculture and science, found inspiration in Michurin's story of perseverance and dedication. The film became particularly popular in rural areas where Michurin's agricultural innovations had practical relevance. Audience letters to newspapers and film studios frequently expressed admiration for the film and its message about the power of human will to transform nature. The film's success led to increased public interest in horticulture and plant breeding, with many Soviet citizens attempting to apply Michurin's methods in their own gardens. However, some audience members with scientific backgrounds privately expressed reservations about the film's scientific claims, though such views could not be publicly expressed during the Stalin era. The film continued to be shown in Soviet cinemas and on television for decades, maintaining its popularity with older generations who remembered its original release.

Awards & Recognition

- Stalin Prize, First Class (1949) - Awarded to director Oleksandr Dovzhenko, actors Vladimir Solovyov and Grigori Belov, and cinematographer Yevgeni Andrikanis

- All-Union Film Festival Prize (1948) - Best Director

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour awarded to the production team

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet socialist realism films

- Earlier Soviet biographical films like 'Chapaev' (1934)

- Dovzhenko's own earlier works 'Earth' (1930) and 'Arsenal' (1929)

- Scientific documentaries of the period

- Russian literary traditions of the 'superfluous man' reinterpreted for Soviet ideology

This Film Influenced

- 'The Great Scientist' (1950) - Soviet biopic about another scientist

- 'Nine Days of a Year' (1962) - Soviet film about nuclear physicists

- 'Andrei Rublev' (1966) - Tarkovsky's film influenced by Dovzhenko's style

- Later Soviet biographical films of the 1950s-60s

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Gosfilmofond archive in Russia and has been digitally restored. The original camera negatives are stored in climate-controlled facilities, and several high-quality prints exist in film archives around the world. A digital restoration was completed in 2010 as part of a broader project to preserve classic Soviet films. The restored version has been shown at various film festivals and is available in high definition for archival purposes.