Metropolis

"The Masterwork of Science Fiction! The Mightiest of All Motion Pictures!"

Plot

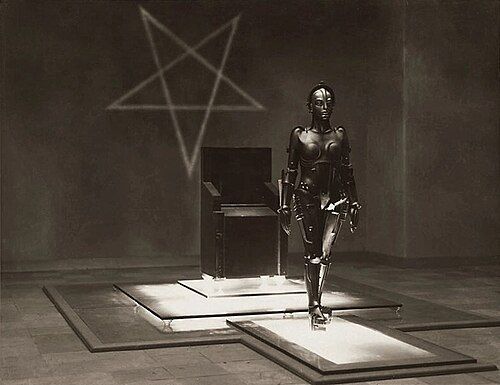

In the futuristic city of Metropolis, society is starkly divided between the wealthy elite who live in luxurious skyscrapers and the impoverished workers who toil underground operating the machines that power the city. Freder Fredersen, the privileged son of Joh Fredersen, the city's autocratic ruler, becomes fascinated with Maria, a compassionate worker who cares for children in the lower city. After witnessing an industrial accident that kills numerous workers, Freder descends into the workers' city and experiences their suffering firsthand, eventually trading places with a worker named Georgy. Meanwhile, Joh Fredersen commissions the mad scientist Rotwang to create a robot duplicate of Maria to manipulate the workers, but the robot incites a violent rebellion that threatens to destroy the city, forcing Freder to become the prophesied mediator between the head and hands of society.

About the Production

The production employed over 37,000 extras and took 17 months to shoot from May 1925 to October 1926. The film's massive sets included the Tower of Babel, which was 30 meters high and required 15,000 extras. The famous Moloch machine scene used 25,000 men in costumes to create the illusion of a living machine. Director Fritz Lang reportedly used real fire for the burning of the false Maria at the stake scene, endangering actress Brigitte Helm.

Historical Background

Metropolis was produced during the final years of the Weimar Republic, a period of intense political and economic instability in Germany following World War I. The film reflected the social tensions of the era, including massive inflation, unemployment, and growing class divisions. The 1920s saw the rise of both communism and fascism in Germany, with workers' movements becoming increasingly organized. The film's themes of industrial exploitation and class warfare directly addressed contemporary concerns about labor conditions in rapidly industrializing cities. The hyperinflation of 1923 had devastated the German middle class, and by 1927, the economy was recovering but social tensions remained high. The film's production coincided with the Golden Age of German cinema, when German filmmakers were pushing artistic boundaries despite economic hardships. The rise of the Nazi Party was already underway, with Hitler gaining political momentum that would culminate in his appointment as Chancellor in 1933.

Why This Film Matters

Metropolis is arguably the most influential science fiction film ever made, establishing visual and thematic conventions that would define the genre for decades. The film's depiction of a futuristic cityscape with towering skyscrapers, flying vehicles, and mechanized society became the template for countless subsequent science fiction works. Its themes of technology dehumanizing workers and the dangers of unchecked industrialization remain remarkably relevant today. The film influenced the visual style of films ranging from Blade Runner to The Fifth Element, and its imagery has been referenced in music videos, advertisements, and art. The concept of the robot Maria directly influenced the creation of C-3PO in Star Wars, and the film's dystopian vision inspired works like 1984 and Brave New World. The film's preservation and restoration efforts have become a cause célèbre in film preservation circles, symbolizing the importance of saving cinema's cultural heritage.

Making Of

The production of Metropolis was legendary for its scale and ambition. Director Fritz Lang and his wife Thea von Harbou wrote the screenplay based on her 1925 novel. The film's massive sets required the construction of entire cityscapes, with the Tower of Babel set alone costing 1.5 million Reichsmarks. Over 25,000 men, women, and children worked as extras, with some scenes requiring up to 1,000 performers simultaneously. The special effects team, led by Eugen Schüfftan, developed groundbreaking techniques including miniature models, multiple exposures, and mirror effects. The famous transformation scene where the robot becomes Maria involved elaborate makeup and costume work that took hours to apply. During filming, several actors were injured, including Gustav Fröhlich who suffered burns during the flooding sequence. The production was so expensive that it nearly bankrupted UFA, Germany's largest film studio, and led to the studio being taken over by American interests.

Visual Style

The cinematography of Metropolis, primarily by Karl Freund and Günther Rittau, was revolutionary for its time. The film employed groundbreaking techniques including forced perspective to create the illusion of massive cityscapes, multiple exposures to create ghostly effects, and elaborate tracking shots that moved through the massive sets. The use of chiaroscuro lighting created dramatic contrasts between the gleaming upper city and the dark, industrial underworld. The famous shots of workers moving in synchronized fashion were achieved through carefully choreographed long takes that emphasized the mechanical nature of their labor. The transformation scenes used innovative optical printing techniques that were years ahead of their time. The camera work emphasized verticality throughout the film, with shots looking up at towering buildings and down into industrial pits, reinforcing the film's themes of social hierarchy.

Innovations

Metropolis pioneered numerous technical innovations that would influence filmmaking for decades. The Schüfftan process, developed by cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan, used mirrors to combine actors with miniature models, creating realistic scenes of massive scale. The film featured some of the most elaborate miniature work ever attempted, with detailed models of the city and machinery that were seamlessly integrated with live action. The special effects team developed sophisticated techniques for creating the robot Maria's transformation, including stop-motion animation and multiple exposure photography. The film's use of moving cameras was revolutionary, with camera movements that were technically difficult but visually stunning. The massive sets included working machinery and hydraulic systems that allowed for dynamic action sequences. The film's editing techniques, particularly in the montage sequences, were innovative in their use of rhythm and visual metaphor to convey complex ideas.

Music

As a silent film, Metropolis was originally accompanied by live musical performances. The original German premiere featured a score by Gottfried Huppertz, a 60-piece orchestral work that was one of the most elaborate film scores of the silent era. Huppertz's score incorporated leitmotifs for different characters and themes, including a distinctive theme for the machine and separate motifs for Maria and the robot. The score was performed live at screenings but was largely forgotten after the silent era ended. Modern restorations have revived Huppertz's original score, which has been recorded by several orchestras. Various composers have created new scores for different releases, including Giorgio Moroder's 1984 version with pop music and a 2011 version by the Alloy Orchestra. The diversity of musical interpretations reflects the film's enduring appeal and adaptability to different artistic sensibilities.

Famous Quotes

There can be no understanding between the hand and the brain unless the heart acts as mediator.

HEAD and HANDS need a mediator. The mediator between HEAD and HANDS must be the HEART!

One man's hymn of praise is another man's blasphemy.

It is their hearts that are not in harmony.

We will build our own tower of Babel.

Moloch! Consume my workers!

The Mediator Between Head and Hands Must Be the Heart!

I have seen the future! It works!

Death is the sleep of the heart.

Without the heart, there can be no understanding between the hand and the brain.

Memorable Scenes

- The opening sequence showing the massive industrial machinery and synchronized workers moving like clockwork parts

- The transformation scene where Rotwang converts the robot into a duplicate of Maria using elaborate special effects

- The Tower of Babel scene with thousands of workers hauling blocks to build the monument

- The robot Maria's erotic dance performance that drives the wealthy elite into a frenzy

- The flooding of the workers' city when the children are trapped in the lower levels

- The climactic scene where Freder becomes the mediator between the workers and the city's rulers

- The Moloch machine vision where workers are fed into a giant mechanical mouth

- The burning of the false Maria at the stake by the angry workers

- The final reconciliation scene on the steps of the cathedral with the three-way handshake

- The aerial shots of the futuristic city with flying vehicles moving between towering buildings

Did You Know?

- The film was the most expensive silent film ever made at the time of its release, costing approximately 7 million Reichsmarks

- Adolf Hitler was reportedly a great admirer of the film, though Fritz Lang claimed that Joseph Goebbels offered him control of German film studios, which prompted Lang to flee Germany the next day

- The original cut was 153 minutes, but American and British distributors heavily edited it down to about 90 minutes, removing significant portions of the plot

- The robot Maria's transformation scene was created using the Schüfftan process, an early special effects technique developed by cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan

- Brigitte Helm played both the real Maria and the robot Maria (Maschinenmensch), requiring hours of makeup application for the robot role

- The film's themes were partly inspired by Lang's first view of New York City in 1924, particularly the nighttime skyline

- A complete copy of the original version was thought lost until 2008, when a damaged 16mm print was discovered in Buenos Aires, Argentina

- The film's special effects were so advanced that many techniques pioneered in it would be used for decades afterward

- The film was banned in Nazi Germany for its 'decadent' and 'degenerate' art style, despite Hitler's admiration for it

- The iconic poster image of the robot Maria was created after the film's production and was not actually seen in the movie itself

What Critics Said

Upon its initial release, Metropolis received mixed reviews from critics. Many praised its technical achievements and visual spectacle but criticized its melodramatic plot and simplistic message. The New York Times called it 'a technical marvel with a somewhat childish moral,' while Variety noted its 'extraordinary production values' but found the story 'confusing.' The film's heavily edited American version was particularly criticized for losing much of its narrative coherence. Over time, critical opinion has shifted dramatically, with modern critics hailing it as a masterpiece. Roger Ebert included it in his Great Movies collection, calling it 'one of the great achievements of the silent era.' The restored versions released after 2002 have been universally praised, with critics noting how the recovered footage transforms the film from a visual spectacle into a coherent and powerful narrative.

What Audiences Thought

Initial audience reception to Metropolis was disappointing, particularly in Germany where audiences found its length and complex narrative challenging. The film's high ticket prices and the country's economic conditions limited its domestic appeal. In the United States, the heavily edited version confused audiences and failed to generate significant interest. However, over the decades, Metropolis has developed a devoted cult following and is now considered a classic. The film's reputation has grown through film societies, art house screenings, and home video releases. Modern audiences, especially those interested in film history and science fiction, have embraced the film's visionary qualities. The various restored versions have introduced new generations to Lang's masterpiece, and it now regularly appears in critics' and audiences' lists of greatest films ever made.

Awards & Recognition

- 1937: Kinema Junpo Award for Best Foreign Language Film (Japan)

- 2001: National Film Registry selection by the Library of Congress

- 2012: UNESCO Memory of the World Register

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Thea von Harbou's 1925 novel Metropolis

- German Expressionism

- Biblical stories (Tower of Babel, Book of Revelation)

- Karl Marx's theories on class struggle

- Fritz Lang's first view of New York City

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's dialectic

- Christian messianic traditions

- Industrial Revolution literature

- German Romanticism

- Art Deco architecture

This Film Influenced

- Blade Runner

- The Matrix

- Dark City

- Brazil

- Star Wars

- The Fifth Element

- Akira

- Ghost in the Shell

- Wall-E

- Things to Come

- Just Imagine

- Alphaville

- THX 1138

- Gattaca

- Minority Report

- The Hunger Games

- Divergent

- Ready Player One

- Alita: Battle Angel

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Metropolis has one of the most complex restoration histories in cinema. The original 153-minute version was considered largely lost for decades, with only heavily edited versions surviving. In 2001, a 107-minute restoration was released using footage from various archives worldwide. The breakthrough came in 2008 when a complete 16mm print of the original version was discovered in Buenos Aires, Argentina. This print contained 25 minutes of previously lost footage, though it was damaged and in poor condition. The most complete restoration to date was released in 2010, running 148 minutes and incorporating the newly discovered footage. The film has been preserved by the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation and selected for the National Film Registry and UNESCO's Memory of the World Register. Digital restorations continue to improve the quality of surviving footage, though some scenes remain lost or damaged beyond repair.