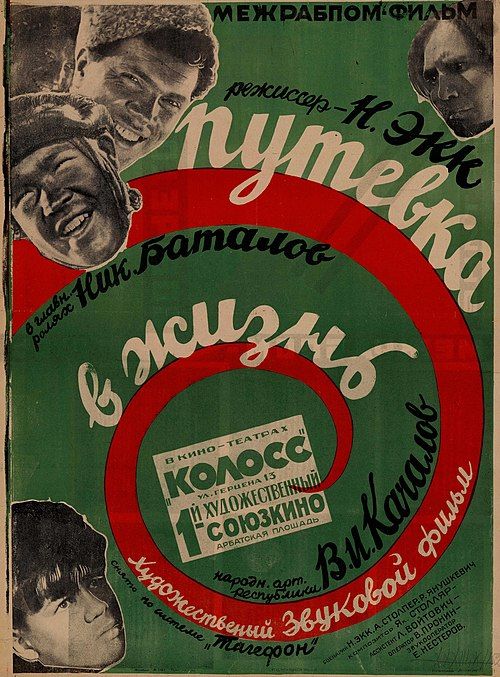

Road to Life

"From street urchins to builders of socialism - a Soviet triumph in juvenile rehabilitation"

Plot

The film follows a group of homeless street children in early Soviet Russia who are rounded up and sent to the FZD (Factory-Plant Children's Commune), a revolutionary labor camp designed to rehabilitate wayward youth through collective work and education. The commune operates without guards or traditional punishment, relying instead on mutual responsibility and socialist principles to transform the young delinquents into productive Soviet citizens. When the commune builds a railroad to connect with the outside world, criminal elements attempt to sabotage the project, resulting in the tragic death of one of the reformed youths. Despite this setback, the commune members unite to complete the railroad, demonstrating the triumph of Soviet collective spirit and the success of their revolutionary rehabilitation methods.

About the Production

The film was groundbreaking as one of the first Soviet sound films, using the new technology to enhance its propaganda message. Many of the child actors were actual former homeless children recruited from Moscow's streets, adding authenticity to their performances. The production faced significant technical challenges with early sound recording equipment, often requiring multiple takes. Director Nikolai Ekk spent months researching actual labor communes and interviewing former besprizorniki (homeless children) to ensure accuracy. The railroad construction scenes were filmed using actual railway workers and equipment, with the young actors participating in real construction work.

Historical Background

The film was produced during the First Five-Year Plan (1928-1932), a period of rapid industrialization and social transformation in the Soviet Union. The issue of besprizorniki (homeless children) was a major social problem, resulting from the upheavals of World War I, the Russian Revolution, and the Civil War. The Soviet government established labor communes as an experimental solution to juvenile delinquency, promoting collective rehabilitation over traditional punishment. The film served as powerful propaganda for the Soviet system's ability to solve social problems through socialist methods. Its international release came at a time when the Great Depression was causing widespread homelessness and unemployment in capitalist countries, making the Soviet solution appear attractive to foreign audiences.

Why This Film Matters

'Road to Life' established several important precedents in Soviet and world cinema. As one of the first successful Soviet sound films, it demonstrated how the new technology could enhance social messaging rather than merely entertain. The film's use of non-professional actors influenced subsequent Soviet cinema, particularly the socialist realist style that would become dominant in the 1930s. Its international success proved that Soviet films could compete artistically and technically with Western productions. The film's humanistic approach to social problems, while serving propaganda purposes, also influenced how juvenile delinquency was portrayed in cinema worldwide. It remains a key document for understanding early Soviet cultural policy and the transition from silent to sound film in non-Western cinema.

Making Of

The making of 'Road to Life' was as revolutionary as its subject matter. Director Nikolai Ekk, a former theater director, insisted on using non-professional actors to maintain authenticity. He spent months living among Moscow's homeless children to understand their lives and mannerisms. The production team built an actual railroad spur for the filming, with the young actors participating in real construction work under supervision. The sound recording equipment, imported from Germany, was primitive by modern standards, requiring the actors to remain relatively still during dialogue scenes. The film's climactic sequence, featuring the railroad completion, was shot over several weeks with multiple cameras to capture the massive scale of the operation. Many of the child actors formed lasting bonds during production, with several continuing to work in Soviet cinema in various capacities.

Visual Style

The cinematography by Vladimir Proppin and Leonid Kosmatov combined documentary-style realism with dramatic composition. The film made innovative use of mobile cameras during the railroad construction sequences, creating dynamic movement that enhanced the sense of collective labor. The contrast between the dark, chaotic streets where the homeless children live and the bright, orderly environment of the commune was achieved through careful lighting design. The sound recording, while technically challenging for the period, effectively used both diegetic and non-diegetic elements to create emotional impact. The film's visual style evolved from gritty realism in the early scenes to more idealized compositions as the children are reformed, reflecting their transformation.

Innovations

As one of the first Soviet sound films, 'Road to Life' pioneered several technical innovations in Soviet cinema. The production team developed new techniques for recording dialogue in outdoor locations, a significant challenge with early sound equipment. The film's use of synchronized sound during large-scale construction scenes required the development of specialized microphone placement strategies. The editing techniques for combining visual and audio elements influenced subsequent Soviet sound films. The production also experimented with early forms of dubbing to improve audio quality in difficult recording conditions. These technical achievements helped establish Soviet cinema as capable of producing sophisticated sound films comparable to Western productions.

Music

The musical score was composed by Dmitri Kabalevsky in one of his earliest film assignments. The soundtrack featured a mix of original compositions and popular Soviet songs of the period, including 'The Young Guard' which became associated with the film. The sound design was particularly innovative for its use of natural sounds from the construction site and the commune, creating an authentic auditory environment. The film's audio quality was considered superior to many early sound films due to the use of German recording equipment and careful post-production work. The musical themes emphasized hope, collective effort, and the triumph of socialist ideals over individual despair.

Did You Know?

- This was the first Soviet sound film to receive international recognition, winning an award at the Venice Film Festival in 1932

- Many of the young actors were actual former homeless children recruited from Moscow's streets, not professional actors

- The film was shown in the United States in 1932 under the title 'Road to Life' and was praised by American critics for its social message

- Director Nikolai Ekk was only 28 years old when he made this film, his directorial debut

- The FZD commune depicted in the film was based on a real institution that operated near Moscow

- The film's success led to a wave of Soviet films focusing on juvenile rehabilitation and social issues

- The railroad sabotage scene was controversial for its depiction of violence against children

- The film was banned in Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy for its socialist propaganda content

- A young Mikhail Romm worked as an assistant director on this film before becoming a renowned director himself

- The film's soundtrack was one of the first to use diegetic sound extensively in Soviet cinema

What Critics Said

Contemporary Soviet critics praised the film as a masterpiece of socialist realism, with Pravda calling it 'a triumph of Soviet cinema.' Western critics were surprisingly receptive, with The New York Times noting its 'sincere and moving portrayal' of youth rehabilitation. The film's technical achievements in sound recording were widely acknowledged, even by critics who disagreed with its political message. Modern film historians view it as an important transitional work, marking the shift from avant-garde Soviet cinema of the 1920s to the more conventional socialist realist style of the 1930s. While some criticize its overt propaganda elements, most acknowledge its artistic merits and historical importance.

What Audiences Thought

The film was enormously popular in the Soviet Union, drawing large crowds in major cities and becoming one of the highest-grossing Soviet films of 1931. Audiences were particularly moved by the authentic performances of the child actors and the film's emotional climax. International audiences responded positively as well, with the film proving successful in Europe and the United States. Many viewers reported being deeply affected by the story of redemption and the film's portrayal of collective effort overcoming individual hardship. The film's success led to increased public support for the Soviet juvenile rehabilitation system and inspired similar programs in other countries.

Awards & Recognition

- Honorary Diploma at the 1st Venice International Film Festival (1932)

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour awarded to director Nikolai Ekk (1932)

- Stalin Prize nomination (though not awarded, the nomination was significant)

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Soviet montage theory

- Socialist realist literature

- Documentary filmmaking traditions

- German expressionist cinema

- American social problem films

This Film Influenced

- The Great Citizen

- 1938

- The Young Guard

- 1948

- The Return of Maxim

- 1937

- The Rainbow

- 1944

- The Beginning of Life

- 1940

- ],

- similarFilms

- The Children of the Sun,1926,The New Babylon,1929,Happiness,1935,The Girl with a Hat,1937,The Seven Brave Men,1936,],,famousQuotes,We don't need guards here - we guard ourselves with our conscience and our work,Every hand that works builds not just rails, but a new life for all of us,The street took our childhood, but the commune gives us back our future,One person alone is weak, but together we can move mountains and lay tracks to tomorrow,memorableScenes,The opening sequence showing homeless children sleeping in Moscow's train stations, filmed with documentary realism,The first day at the commune where the children discover there are no guards or locked doors,The massive railroad construction sequence showing hundreds working in perfect coordination,The tragic death scene of the young worker during the sabotage attempt,The final celebration as the first train arrives at the newly completed station,preservationStatus,The film has been preserved in the Gosfilmofond of Russia (State Film Archive) and has undergone restoration in the 1990s. A restored version with improved sound quality was released in 2005. While some original elements have deteriorated due to the unstable nitrate stock used in the 1930s, the film is considered to be in relatively good condition for its age. Multiple copies exist in international archives, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the British Film Institute.,whereToWatch,Available on DVD from Russian Cinema Council (Ruscico) with English subtitles,Streaming on Soviet film archive websites,Occasionally screened at film festivals specializing in classic cinema,Available in some university film collections,Can be viewed at the Museum of Modern Art film archive in New York