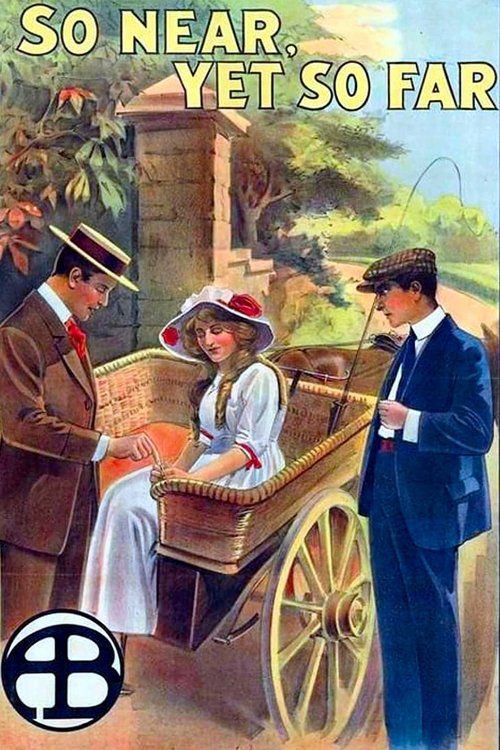

So Near, Yet So Far

Plot

A young man experiences love at first sight when he encounters a beautiful young woman, but his overwhelming shyness prevents him from approaching her directly. Complicating matters further, several other suitors boldly pursue the young woman, creating additional obstacles for the timid protagonist. Through a fortunate coincidence, both the young man and the woman of his dreams unknowingly find themselves staying at the same house, which belongs to mutual friends. As fate brings them into close proximity, the young man struggles to overcome his inhibitions while rival suitors continue their aggressive courtship. The romantic tension reaches its climax when dangerous robbers infiltrate the property outside the house, threatening the safety of everyone within. In the chaos that ensues, the young man must finally find his courage to protect the woman he loves and declare his feelings before it's too late.

About the Production

This film was produced during D.W. Griffith's most prolific period at Biograph, where he directed hundreds of short films between 1908-1913. The production utilized Biograph's standard practice of shooting quickly and efficiently, often completing films in just one or two days. Mary Pickford was already becoming a major star by 1912, and Griffith frequently cast her in these sentimental romances that showcased her natural screen presence. The film was likely shot on Biograph's studio sets with minimal location work, typical of the company's cost-effective production methods.

Historical Background

1912 was a pivotal year in American cinema, marking the transition from short novelty films to more sophisticated storytelling. The film industry was still centered in the New York area, particularly Fort Lee, New Jersey, where Biograph maintained its primary studio. This period saw the rise of the star system, with actors like Mary Pickford becoming household names and major draws for audiences. The year also witnessed significant technological advancements in film equipment, though the basic grammar of cinema was still being established by pioneering directors like Griffith. Socially, 1912 America was experiencing rapid industrialization and urbanization, and films like this provided escapist entertainment for working-class audiences. The film industry was also facing legal challenges, as Thomas Edison's Motion Picture Patents Company attempted to control film production through patent enforcement, though independent producers like Biograph were increasingly resisting this monopoly.

Why This Film Matters

This film represents an important milestone in the development of cinematic language and romantic storytelling in early American cinema. As part of Griffith's extensive body of work at Biograph, it contributed to the establishment of narrative techniques that would become standard in filmmaking. The film's exploration of shyness as an obstacle to romance reflected Victorian-era social mores that were still prevalent in 1912 America, particularly regarding courtship and gender roles. Mary Pickford's performance helped cement her status as 'America's Sweetheart,' a persona that would dominate American popular culture for the next decade. The film's structure—combining romance with danger and action—demonstrated Griffith's ability to blend genres within the short format, a technique that would influence countless future filmmakers. Additionally, the film's preservation and study provides modern audiences with insight into early 20th-century social values, fashion, and domestic life.

Making Of

The production of 'So Near, Yet So Far' exemplified the rapid-fire efficiency of Biograph's output during Griffith's tenure. Griffith was known for his meticulous planning, often creating detailed storyboards and shot lists before filming began. The cast, particularly Mary Pickford, had developed an intuitive understanding of Griffith's directing style, requiring minimal verbal instruction on set. Pickford's natural acting style contrasted with the more theatrical approach common in earlier films, and Griffith encouraged this realism in his performers. The film was likely shot in just one or two days, with the cast and crew working long hours to complete multiple films simultaneously. The robber scenes would have required careful coordination and timing, as action sequences were still relatively new to cinema in 1912. Griffith was already experimenting with camera techniques that would later become his signature, including close-ups and cross-cutting to build tension.

Visual Style

The cinematography in this film reflects the Biograph Company's style during this period, characterized by static camera positions and careful composition within the frame. Billy Bitzer, Griffith's regular cinematographer, likely handled the camera work, bringing his characteristic attention to lighting and composition. The film would have utilized natural lighting when possible, supplemented by artificial lighting for interior scenes. Camera movements were minimal, as mobile camera shots were still technically challenging and rarely used in 1912. The visual storytelling relied heavily on composition and actor placement within the frame to convey relationships and emotions. Griffith was already experimenting with close-ups for emotional emphasis, though these were used sparingly compared to his later works. The film's visual style would have included careful attention to period details in costumes and set design, reflecting the Biograph Company's commitment to production values despite their rapid production schedule.

Innovations

While not among Griffith's most technically innovative works, this film demonstrates several important technical practices of the era. The use of cross-cutting between the romantic storyline and the approaching robbers shows Griffith's mastery of parallel editing to build suspense. The film's single-reel format required efficient storytelling within approximately 12 minutes, influencing the development of concise narrative techniques. The production likely utilized Biograph's patented camera equipment, which was among the most advanced of its time. The film's editing techniques, while simple by modern standards, represented the cutting edge of cinematic grammar in 1912. The lighting techniques used for interior scenes were becoming increasingly sophisticated, allowing for more naturalistic performances. The film's preservation on 35mm nitrate stock, while dangerous for long-term storage, provided excellent image quality for contemporary audiences.

Music

As a silent film, 'So Near, Yet So Far' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibition. The specific musical score was not recorded or standardized, as theaters typically employed musicians who would improvise or select appropriate pieces to accompany the film. Larger theaters might have had a small orchestra or organist, while smaller venues might have used just a pianist. The music would have followed the dramatic structure of the film, with romantic themes for the love scenes and more suspenseful music during the robbery sequence. Popular songs of the era, classical pieces, or specially composed mood music might have been used depending on the resources of each theater. The lack of synchronized sound meant that musical accompaniment varied significantly between different exhibition venues, making each viewing experience unique. The film's emotional content would have been heavily dependent on the skill and interpretation of the accompanying musicians.

Famous Quotes

(Silent film - no dialogue quotes available)

Memorable Scenes

- The climactic sequence where the shy protagonist must finally overcome his fear to protect his beloved from the robbers, representing both physical and emotional courage in the face of danger.

Did You Know?

- This film was one of approximately 300 short films D.W. Griffith directed for the Biograph Company between 1908 and 1913.

- Mary Pickford was only 19 years old when she appeared in this film, though she was already one of the most popular actresses in the world.

- The film was shot on 35mm film at Biograph's standard frame rate of 16 frames per second.

- Walter Miller and Robert Harron were both regular collaborators with Griffith during this period, appearing in dozens of his films.

- Biograph films of this era were typically rented to theaters for a flat fee rather than sold outright, making individual box office tracking impossible.

- The film's title reflects Griffith's fascination with the theme of missed opportunities and romantic misunderstandings, which he explored in numerous shorts.

- This was released during the same year Griffith made his first feature-length film attempts, though he would continue making shorts through 1913.

- The robbers subplot was a common Griffith device to create dramatic tension and force character development.

- Biograph's studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey, was considered the first motion picture production center in America before the industry moved to Hollywood.

- The film was likely edited by Griffith himself, as directors of this era typically performed their own editing.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critical reception for individual Biograph shorts in 1912 is difficult to document, as film criticism was still in its infancy and most publications focused on the industry rather than specific films. However, trade publications like The Moving Picture World generally praised Griffith's work at Biograph for its sophistication and emotional depth. Modern film historians and critics recognize films like this as important steps in Griffith's development as a filmmaker and in the evolution of American cinema. The film is often cited in scholarly works examining Griffith's early career and his development of cinematic techniques. Critics particularly note how Griffith used the short format to experiment with narrative structure and character development, practices that would influence his later, more famous works. The film is generally regarded as a solid example of Griffith's romantic shorts from this period, though not among his most groundbreaking or innovative works of the era.

What Audiences Thought

Audience reception for Biograph shorts in 1912 was generally positive, particularly for films featuring popular stars like Mary Pickford. Contemporary accounts suggest that Pickford's films were especially popular with female audiences, who identified with her natural acting style and the relatable romantic situations she portrayed. The combination of romance and danger in this film would have appealed to the broad audience base that nickelodeons and early movie theaters attracted during this period. The theme of shy lovers overcoming obstacles resonated with working-class audiences who often faced similar social challenges in their own lives. While specific audience reactions to this particular film are not documented, the continued demand for similar romantic shorts throughout 1912 indicates their popularity. The film's success can be inferred from Biograph's continued production of similar romantic dramas throughout this period, suggesting strong audience demand for this type of content.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Earlier Biograph shorts by Griffith

- Victorian literature and melodrama

- Stage plays of the era

- Contemporary social norms

- 19th-century romantic literature

This Film Influenced

- Later Griffith romantic shorts

- Biograph productions of 1912-1913

- Early Hollywood romantic melodramas

- Mary Pickford's later feature films

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The preservation status of this specific 1912 Biograph short is uncertain. Many Biograph films from this period have survived through various archives and collections, particularly the Library of Congress and the Museum of Modern Art. However, some films from this era have been lost due to the deterioration of nitrate film stock. If the film survives, it would likely exist as a 35mm print or digital copy in a film archive. The film may have been included in various Griffith retrospective collections or DVD compilations of his early work.