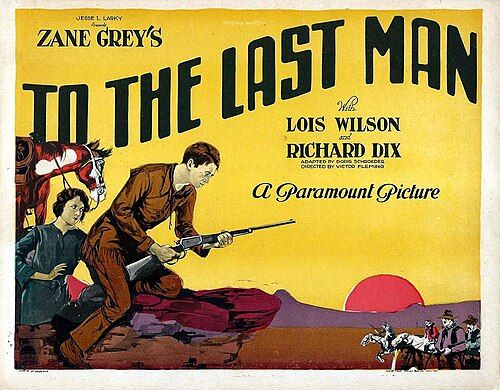

To the Last Man

"A Romance of the Arizona Range"

Plot

In this gripping Western drama, two families, the Colbys and the Dents, are locked in a bitter feud over land and water rights in the Arizona territory. Jean Colby (Richard Dix) and Ellen Dent (Lois Wilson) fall in love despite their families' animosity, creating a Romeo and Juliet-esque romance amidst the violence. When sheepherders begin encroaching on cattle ranching territory, the conflict escalates dramatically, with both sides resorting to increasingly brutal tactics. The film culminates in a devastating range war that tests the boundaries of loyalty, love, and survival in the harsh American West. As the body count rises and tensions reach their breaking point, the young lovers must choose between family allegiance and their own future together.

About the Production

The film was shot on location in Arizona to capture the authentic Western landscape, which was somewhat unusual for the time as many Westerns were filmed on studio backlots. Victor Fleming, who would later direct such classics as 'Gone with the Wind' and 'The Wizard of Oz,' was still early in his directorial career but already showing his talent for handling large-scale outdoor productions. The production faced challenges with the extreme desert heat and managing large numbers of cattle and horses for the action sequences.

Historical Background

The early 1920s marked a golden age for American cinema, with Hollywood establishing itself as the global center of film production. Westerns were particularly popular during this period, reflecting America's fascination with its frontier past and the mythology of the West. The film was released during the Roaring Twenties, a time of economic prosperity and cultural change in America, yet audiences still gravitated toward stories of the simpler, more rugged past. The year 1923 also saw significant developments in the film industry, including the establishment of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America's Production Code, though it wouldn't be strictly enforced until later in the decade. The film's themes of land disputes and range wars reflected real historical conflicts that had shaped the American West, making it resonate with audiences who were often only one or two generations removed from the frontier era.

Why This Film Matters

'To the Last Man' represents an important example of the silent Western genre at its peak. The film helped solidify Richard Dix's status as a major Western star, leading to his continued success in the genre throughout the 1920s. It also demonstrated Paramount Pictures' commitment to producing high-quality Westerns with substantial budgets and production values. The film's blend of romance and action elements influenced the development of the Western genre, showing that these films could appeal to broader audiences beyond just male viewers. The adaptation of Zane Grey's work was part of a broader trend of bringing popular Western literature to the screen, helping to create a shared cultural mythology of the American West that would persist for decades. The film's emphasis on location shooting also influenced subsequent Western productions, helping to establish the importance of authentic settings in the genre.

Making Of

The production of 'To the Last Man' was a significant undertaking for Paramount Pictures in 1923. Director Victor Fleming, who had previously worked as a cinematographer, brought a distinctive visual style to the film, utilizing the vast Arizona landscapes to create a sense of epic scale. The cast and crew endured harsh filming conditions, including temperatures exceeding 100 degrees Fahrenheit. The film's action sequences, particularly the cattle drives and gunfights, required extensive planning and coordination. Richard Dix performed many of his own stunts, including riding scenes and dangerous confrontations. The romance between Dix and Wilson's characters was emphasized in the marketing, as Paramount sought to appeal to both male and female audiences. The film's script went through several revisions to balance the action elements with the romantic storyline, a common practice in Westerns of the era to broaden their appeal.

Visual Style

The cinematography of 'To the Last Man' was handled by James Wong Howe, who was already establishing himself as one of Hollywood's most talented cameramen. Howe utilized the expansive Arizona landscapes to create sweeping, epic shots that emphasized the isolation and beauty of the Western setting. The film features impressive tracking shots during cattle drive sequences and dynamic camera movement during action scenes. Howe experimented with natural lighting techniques, particularly in the outdoor scenes, to create a more authentic and visually striking look. The contrast between the vast, empty landscapes and the intimate moments between the lovers creates a powerful visual narrative that enhances the story's emotional impact. The film's visual style was considered innovative for its time and helped establish new standards for Western cinematography.

Innovations

The film showcased several technical innovations for its time, particularly in its use of location photography. The production employed portable cameras and equipment that allowed for greater mobility in the difficult Arizona terrain. The action sequences, particularly the cattle drives and gunfights, demonstrated advanced techniques for coordinating large numbers of animals and extras safely and effectively. The film also utilized early special effects techniques, including matte paintings to enhance the scope of certain scenes. The intertitles were designed with artistic flourishes that reflected the Western theme, showing attention to detail in all aspects of production. The film's preservation of action continuity across multiple locations was considered technically impressive for the period.

Music

As a silent film, 'To the Last Man' would have been accompanied by live musical performance in theaters during its original release. The score would typically have been compiled from classical pieces and popular songs of the era, with theater organists or small orchestras providing accompaniment. The music would have been synchronized to enhance the emotional impact of key scenes, with romantic themes for the love scenes and dramatic, rhythmic music for the action sequences. No original composed score survives, and specific details about the musical accompaniment used during the film's initial run are not documented. The film's intertitles would have been accompanied by appropriate musical cues to emphasize their dramatic significance.

Famous Quotes

Love knows no boundaries, not even those drawn by hate and generations of feud

In this land, a man's word is his law and his gun is his justice

The West was won with blood and sacrifice, and it will be kept the same way

Sometimes the hardest battle is not against your enemies, but against your own family

Memorable Scenes

- The dramatic confrontation between the Colby and Dent families at the water hole, where tensions erupt into violence

- The romantic meeting between Jean and Ellen at sunset among the Arizona mesas

- The massive cattle drive sequence showcasing hundreds of cattle across the open range

- The climactic gun battle between the feuding families as storm clouds gather overhead

Did You Know?

- This film was based on a story by Zane Grey, one of the most popular Western writers of the early 20th century

- Victor Fleming was primarily known as a cinematographer before transitioning to directing, and his visual expertise is evident in the film's striking landscape shots

- Richard Dix was one of Paramount's biggest stars in the early 1920s and was paid $2,500 per week for this film

- The film featured over 500 cattle and 100 horses, requiring extensive coordination by the production team

- A remake of 'To the Last Man' was produced in 1933 starring Randolph Scott, though the plot was significantly altered

- The original film title was 'The Last Man' but was changed to 'To the Last Man' before release

- Lois Wilson was one of the few actresses of the era who successfully transitioned from silent films to talkies

- Noah Beery Sr. was the father of Noah Beery Jr., who would later have a long career in film and television

- The film's production coincided with a period of intense Western popularity in Hollywood, with dozens of Westerns being produced annually

- Paramount invested heavily in the film's marketing, emphasizing its authentic Arizona locations and the star power of its cast

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised 'To the Last Man' for its spectacular scenery and action sequences. Variety noted that the film 'delivers plenty of excitement and romance' and particularly commended the Arizona locations for adding authenticity to the production. The Motion Picture News highlighted Richard Dix's performance as 'strong and convincing' in the lead role. Modern critics have had limited opportunity to evaluate the film due to its preservation status, but film historians consider it a representative example of the mid-1920s Western genre. The film is often discussed in the context of Victor Fleming's early directorial work, showing his developing talent for handling large-scale productions before his later successes in the sound era.

What Audiences Thought

The film was generally well-received by audiences upon its release, particularly in Western-loving markets in the American Midwest and West. Richard Dix's popularity helped draw crowds to theaters, and the combination of romance and action appealed to a broad demographic. Audience letters published in trade magazines of the time praised the film's thrilling action sequences and the chemistry between the leads. The film performed solidly at the box office, though exact figures are not available. Its success helped cement Paramount's reputation as a producer of quality Westerns and contributed to the studio's strong financial performance in 1923. The film's popularity also led to increased demand for Zane Grey adaptations, resulting in several more productions based on his work throughout the 1920s.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Zane Grey's Western novels

- Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet

- Earlier Western films such as 'The Great Train Robbery' (1903)

- The tradition of American frontier literature

This Film Influenced

- To the Last Man (1933 remake)

- Subsequent Paramount Western productions of the 1920s

- Later films featuring feuding families in Western settings

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

Unfortunately, 'To the Last Man' (1923) is considered a lost film. No complete copies are known to survive in any film archives or private collections. This was not uncommon for silent films, as many were destroyed or lost due to the unstable nature of nitrate film stock, lack of preservation efforts in the early decades of cinema, and the perceived obsolescence of silent films after the transition to sound. Only a few production stills and promotional materials survive to document the film's existence. The 1933 remake starring Randolph Scott does survive and provides some indication of the story's content, though it was significantly altered for the sound era.