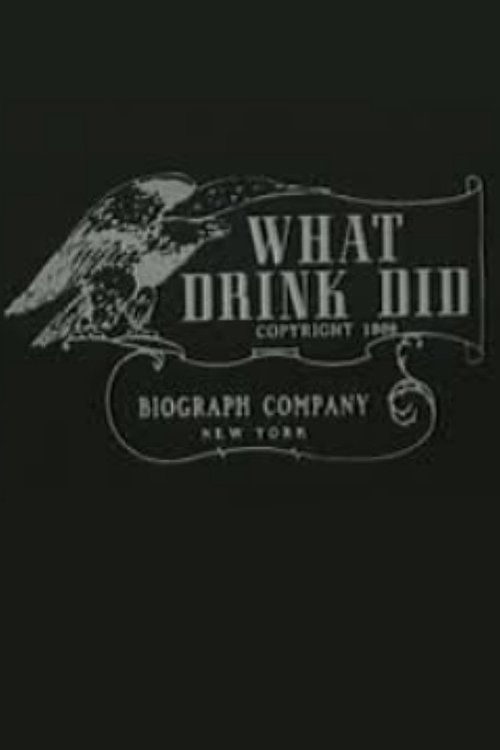

What Drink Did

Plot

A dedicated carpenter and family man leaves his wife and two young daughters each morning to work diligently at his carpentry shop. Initially, he refuses when offered a beer with his lunch, maintaining his principles and work ethic. However, after his shift ends, two persistent coworkers gradually persuade him to join them for a single 'refreshing malt beverage,' which leads to another and then another. The film traces his descent from responsible family provider to habitual drinker, showing the devastating impact on his home life as his neglected family suffers while he spends increasingly more time and money at the tavern. The narrative culminates in a powerful demonstration of how one seemingly innocent decision to have a drink can spiral into addiction and ruin.

About the Production

Filmed in the early days of cinema when Biograph was still primarily based in New York before relocating to California. The film was shot on 35mm film at Biograph's studio facilities, using natural lighting as artificial lighting was still primitive. The production would have been completed in just one or two days, typical of the rapid production schedule of the era where Griffith was directing multiple films per month.

Historical Background

Released in June 1909, 'What Drink Did' emerged during a transformative period in American cinema and society. The film industry was still in its infancy, with nickelodeons providing cheap entertainment to urban working-class audiences. The Progressive Era (1890s-1920s) was in full swing, bringing social reform movements to the forefront of American consciousness, particularly the temperance movement which would eventually lead to Prohibition in 1920. This film reflected the growing concern about alcohol's impact on families and society, using the new medium of cinema to deliver moral messages to mass audiences. 1909 was also a pivotal year for D.W. Griffith, who was rapidly becoming one of the most important directors in American cinema, developing many of the cinematic techniques that would define narrative film. The film's release coincided with the increasing sophistication of movie storytelling, as filmmakers moved away from simple actualities toward complex narratives with social commentary.

Why This Film Matters

'What Drink Did' represents an important early example of cinema's role as a vehicle for social commentary and moral education. As one of Griffith's temperance films, it demonstrates how early filmmakers recognized the power of motion pictures to influence public opinion and social behavior. The film contributed to the broader cultural conversation about alcohol consumption that was raging in America during the Progressive Era. Its narrative approach of showing the gradual deterioration of a respectable family man through drinking became a template for countless later films dealing with addiction. The film also showcases the emerging star system, with Florence Lawrence's performance helping establish her as one of cinema's first recognizable stars. As part of Griffith's early body of work, it illustrates the director's developing mastery of cinematic language and his ability to use film to explore complex social themes.

Making Of

The film was made during D.W. Griffith's formative period at Biograph, where he was rapidly developing his cinematic language and storytelling techniques. Griffith was known for his meticulous attention to detail even in these early productions, often working closely with his actors to achieve naturalistic performances in an era when theatrical acting was the norm. The production would have been completed with a small crew and minimal equipment, using the basic camera technology available in 1909. Griffith was already experimenting with cross-cutting and parallel editing techniques that would become his trademarks, using them to contrast the husband's drinking with his family's suffering at home. The film's moral message reflected Griffith's own conservative values and the prevailing social attitudes of the Progressive Era.

Visual Style

The cinematography by G.W. 'Billy' Bitzer, Griffith's regular cameraman, utilized the techniques common to 1909 but with Griffith's emerging innovations. The film employed static camera positions typical of the era, but Griffith was already experimenting with different camera angles and distances to enhance emotional impact. The interior scenes were lit using available light supplemented by reflectors, creating the high-contrast look characteristic of early films. Bitzer would have used the Pathe camera, which was standard equipment for Biograph productions. The film likely featured the hand-tinting that was popular during this period, with colors added to enhance mood and differentiate locations. The cinematography emphasized facial expressions and gestures, crucial for storytelling in the silent era.

Innovations

While not technically innovative compared to some of Griffith's other 1909 works, 'What Drink Did' demonstrated his mastery of emerging cinematic techniques. The film made effective use of parallel editing to contrast scenes of the husband's drinking with his family's suffering at home, a technique Griffith was pioneering at this time. The continuity editing maintained clear narrative flow despite the primitive equipment available. The film's effective use of close-ups for emotional moments showed Griffith's understanding of the camera's power to create intimacy with the audience. The production utilized Biograph's standard 35mm film format and the latest camera equipment of the era. The film's pacing and narrative structure represented the growing sophistication of storytelling in early cinema, moving beyond the simple tableaux format of earlier films.

Music

As a silent film, 'What Drink Did' would have been accompanied by live musical performance during theatrical exhibitions. The typical accompaniment would have been a pianist or small ensemble playing popular songs and classical pieces appropriate to the mood of each scene. For the happy family scenes, upbeat popular tunes would have been used, while the drinking scenes might have featured darker, more ominous music. The emotional climax would have been accompanied by dramatic classical pieces. Some larger theaters might have employed a small orchestra. The music was not standardized but selected by the individual theater's musical director based on the film's content and the musicians' repertoire. The score would have been crucial in conveying the film's emotional tone and moral message to the audience.

Famous Quotes

'Just one won't hurt' - the coworkers tempting the protagonist

'I must think of my wife and children' - the husband's initial refusal

'The first drink leads to the last' - implicit moral of the story

Memorable Scenes

- The initial lunch scene where the carpenter refuses the beer, showing his strength of character. The gradual persuasion after work, with each drink seeming more innocent than the last. The cross-cutting sequence contrasting the husband's increasing intoxication with his hungry, waiting family at home. The emotional climax showing the full impact of his drinking on his household. The final scenes suggesting either redemption or continued downfall, depending on the version shown.

Did You Know?

- This film was part of D.W. Griffith's early series of 'social problem' films that addressed contemporary issues like alcoholism, poverty, and social injustice.

- Florence Lawrence, who plays the wife, was known as 'The Biograph Girl' and was one of the first film stars, though audiences didn't know her name until later in 1909.

- The film was released during the height of the temperance movement, just a decade before Prohibition would begin in the United States.

- David Miles, who plays the husband, was one of Griffith's regular actors during his Biograph period, appearing in over 30 of Griffith's films.

- Gladys Egan, one of the child actresses, was a popular child star of the era who appeared in numerous Griffith films before retiring from acting as a teenager.

- The film's title 'What Drink Did' was a common phrase used by temperance advocates to illustrate the destructive power of alcohol.

- This was one of over 40 short films Griffith directed in 1909 alone, demonstrating his incredible productivity during this period.

- The film was distributed on a 'state's rights' basis, meaning different companies could buy the rights to show it in different geographic regions.

- Like many films of this era, it was likely tinted by hand for color effects, particularly blue for night scenes and amber for indoor scenes.

- The tavern scenes were filmed on constructed sets rather than in actual bars, as was common practice for moral films of the period.

What Critics Said

Contemporary critics praised the film for its moral message and emotional power, with trade publications like The Moving Picture World commending its realistic portrayal of the dangers of alcohol. The film was particularly noted for its effective use of cross-cutting to contrast the husband's degradation with his family's suffering. Modern film historians recognize 'What Drink Did' as an important example of early social problem cinema and as evidence of Griffith's developing directorial skills. Critics today appreciate how the film, despite its melodramatic elements, captures the Progressive Era's reformist spirit and demonstrates cinema's potential as a medium for social commentary. The film is often cited in scholarly works about early American cinema and the representation of social issues in silent film.

What Audiences Thought

Early 20th-century audiences responded positively to the film's clear moral message and emotional storytelling. Working-class viewers, many of whom had personal experience with alcohol's impact on families, found the story relatable and moving. The film's temperance theme resonated strongly with the reform-minded audiences who frequented nickelodeons during this period. Contemporary accounts suggest that audiences were particularly affected by the scenes showing the neglected wife and children, which tapped into prevailing Victorian ideas about family and domesticity. The film's straightforward narrative and emotional appeal made it popular across diverse audience groups, from recent immigrants to native-born Americans. Its success helped establish the market for films with social messages and encouraged Biograph and other studios to produce more films addressing contemporary social issues.

Film Connections

Influenced By

- Stage melodramas of the 19th century

- Temperance literature

- Social reform movements

- Earlier Biograph shorts

- Contemporary newspaper stories about alcoholism

- Victorian moral tales

This Film Influenced

- Griffith's later temperance films like 'The Drunkard's Reformation' (1909)

- Other social problem films of the 1910s

- Hollywood's later films about alcoholism

- The 'fallen man' genre in cinema

You Might Also Like

Film Restoration

The film is preserved in the Library of Congress collection as part of the Paper Print Collection, with copies also held at the Museum of Modern Art and other film archives. The survival of this 1909 film is remarkable given that approximately 75% of American silent films have been lost. The preservation was possible because Biograph submitted paper prints for copyright protection, which have since been transferred back to film. The film has been restored and is available for scholarly study and occasional screenings.